A village funeral in Cameroon

Pierre, left, and family members at open casket viewing in Pa Jean’s old house. Close family members dressed in gold and orange traditional clothing. Photo: Ellen Rocco

In May, Pierre and I made an unplanned trip back to his home village of Baligham, Cameroon. Pierre’s father, Pa Jean Mofor, had died after a short illness.

On this, my second visit to Cameroon, I felt like I was going home, too. The familiar airport in Douala, the overnight drive to Mbouda, the rudimentary hotel room, and the red clay mud on the road to Baligham village.

More than anything else, my welcome by the family and village brought tears to my eyes. More people than I can count took my hand and said, “Welcome. Thank you, mama. We hope you are good.” A true homecoming. Most of these people speak little English or French–a local dialect is the primary language and totally unintelligible to me.

Nonetheless, the love and gratitude was palpable. In Cameroonian tradition, the widow and close family members of the deceased are never left alone during the first weeks and months following the death. That I had accompanied Pierre home solidified last year’s initiation into the family. For me, the decision to accompany Pierre was instinct: how could I let him–a son to me–travel alone for two days when he was so deeply grieving his father’s passing?

Death celebrations, or funerals, in Cameroonian villages go on for days, and even weeks. Pa Jean’s body had been held in a morgue in Mbouda so that the funeral could be delayed until Pierre arrived. Several cars and motorbikes followed the hearse on the drive into the village.

On the road to Baligham, signs announcing Pa Jean’s death and funeral were placed at forks. Photo: Ellen Rocco

Our first stop was to see the village chief.

The Chief of Baligham village in his courtyard. We were not allowed to get any closer. The chief is in red, playing with his young child; the other man is the Chief’s assistant. Photo: Ellen Rocco

The exterior of the village palace, the chief’s residence. In this area of Cameroon, the pointed metal roof indicates a high position in the community. Photo: Ellen Rocco

The chief had asked that Pierre and his eldest brother, Vincent, stop by for a brief conversation. Vincent asked me to join them, as well. Pa Jean was a respected elder in the village and, as the chief said to us, a man who had believed in educating all children. Pierre told me that Pa Jean, a tailor by trade, had often found a way to sew for village children who were too poor to buy the required school uniforms.

From the palace, we drove slowly to the family compound, joined along the way by more cars, motorbikes, and foot traffic. Pierre had warned me that there might be 1,000 people at the gathering. I estimated somewhere close to that number on funeral day; and there were hundreds on the following day.

Funeral day in the family compound. Note the blue and white t-shirt on the woman at far right. These were designed as a tribute to Pa Jean by Pierre’s younger brother. Photo: Ellen Rocco

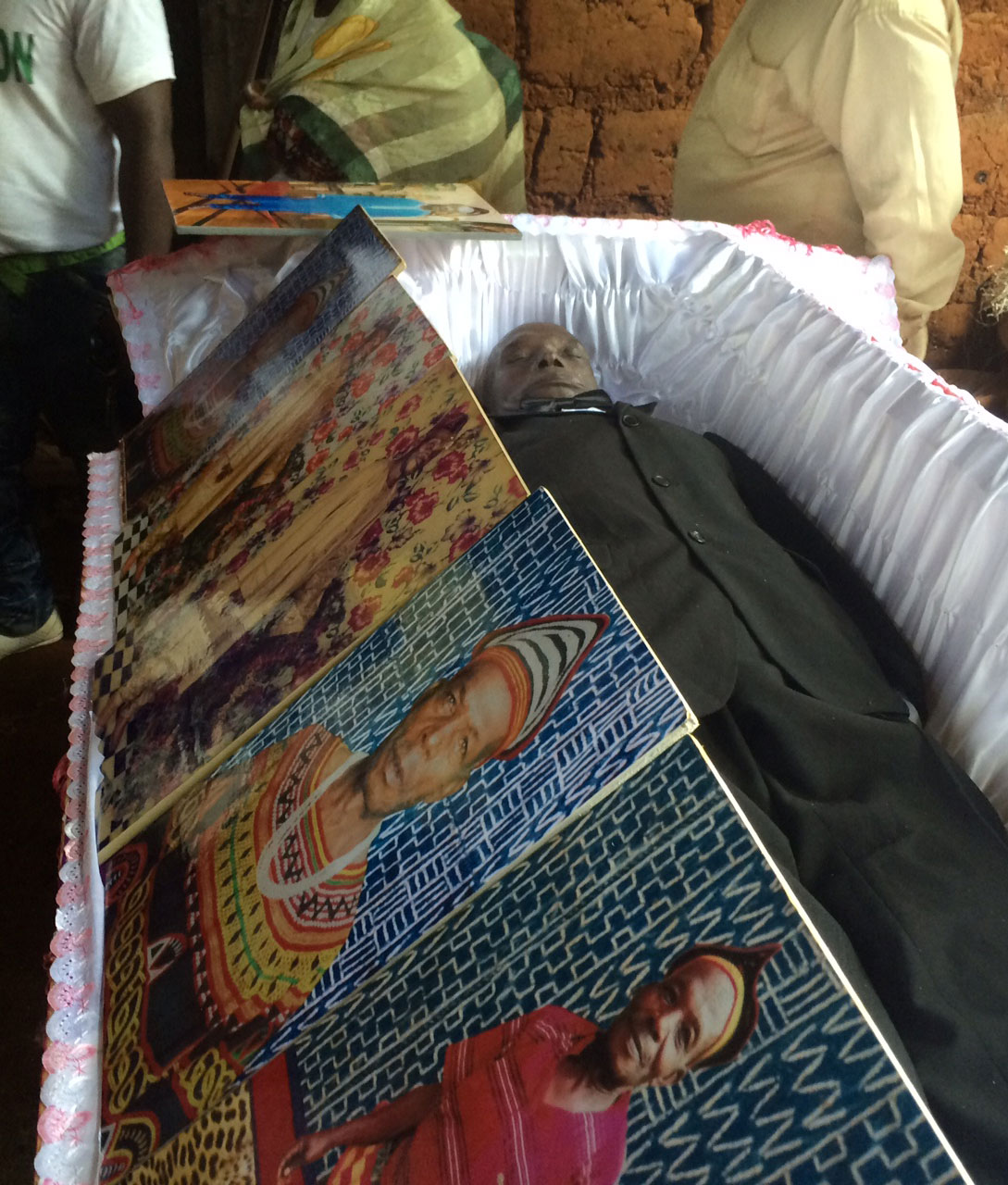

There was very little in the way of a formal service. The coffin was set up in Pa Jean’s old mud brick house and close family members stood nearby as hundreds of people filed past the open casket. Then, the casket was closed and brought outside where a prominent family member and religious leader said a few words, as did Pierre’s eldest siblings.

A village leader eulogizes Pa Jean. Pierre is just to his right holding a portrait of his father. Close family members all dressed in the burnt orange traditional clothing. Photo: Ellen Rocco

In a quiet room, family members are fed. Here, PIerre spends time with nieces and nephews. Photo: Ellen Rocco

Tradition in the village calls for burial immediately adjacent to the dwelling place. Over the course of the funeral afternoon, men dug a deep hole right in front of Pa Jean’s old house and then buried the casket.

Casket about to be lowered into grave dug beside Pa Jean’s front door. Note t-shirts made to honor Pa Jean at his funeral. Photo: Ellen Rocco

There were brief interludes of what seemed like spontaneous singing and dancing, by groups of men, groups of women, and mixed groups.

Here, men and women sing and dance a mourning song.

Among the most moving moments for me was watching Pierre’s mother, Ma Bar, stand up every so often and begin singing and dancing what I intuited was an expression of mourning. Other women always stood with her–never letting her feel alone in her grief. Of course, children–like children everywhere–found a way to be a part of my video, dancing their way into the recording.

On the day following the funeral, members of the family gathered at their late grandfather’s home to honor their ancestor and share more remembrances and food.

Pierre, fourth from left, and some of his siblings gather at their late grandfather’s home. Photo: Ellen Rocco

After two days in the village, Pierre and I took the bus back to Douala. I took a plane back to JFK that night; Pierre stayed on to spend more time with family and friends before returning to the north country later this summer.

Bus station, Mbouda. Most of the cargo space beneath the bus was filled with bags of produce like those shown here. People transport produce to Douala to sell at street markets there. Photo: Ellen Rocco

On the road from Mbouda to Duala, a seven-hour trip. So many unfinished construction projects in Cameroon–this one, according to the sign, “Solid Foundation School.” Photo: Ellen Rocco

If you missed the multi-media story Brit Hanson and I collaborated on last year after my first trip to Cameroon, you’ll find in it more about Pierre and how I came to be Mama Ellen to him. We’re very proud that the piece was recognized with a national Gabriel Award.

More video of village song and dance…

Here are the men:

And the women:

Pa Jean Mofor, 1944-2016

Wearing Against All Odds: Outreach for Learning t-shirt, the NGO started by his son, Pierre Nzuah, to provide scholarships for students and resources for elementary schools in Baligham village.