Fixers to the rescue

The film Wag the Dog introduced me to the notion of “fixer” as a job title when Robert De Niro’s character is hired to “fix” the political environment in the wake of a salacious scandal involving the President. These days, of course, such fixers are obsolete—political figures no longer resort to cover-ups and distractions; they are apt to text about their sins or post them on Facebook.

Photo: Kevin Dooley, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

However, a different kind of professional fixer is making a comeback. Environmentalists, economists, and people with limited incomes welcome the growing interest in repairing things that have typically been treated as disposable. Digital devices, appliances, clothing and other items are getting a new life. Repair shops, once thought extinct, are apparently breeding again, given their recent resurgence.

Re-use centers have been popping up all over the country over the past decade or so, acting as a combination of flea market and repair shop. And “maker spaces,” where people can go to access tools and expertise they need to mend household items themselves, are likewise gaining traction.

If an aging car that would cost $5,000 to replace needs a $200 radiator, no one questions the logic of having that done. But why pay a quarter of the price of a new a laptop computer or smart phone to have the old one fixed up when a new version will probably be out soon? After all, they can be recycled.

It may not be politically correct to say this in public, but not all recycling is created equal. Recycling a glass bottle might save as much as 30% of the energy needed to make it from sand. And according to the U.S. Department of Energy, recycled paper takes 60% less energy than making paper from trees. But the gold standard of recycling is tinfoil. If you recycle your aluminum health-drink (I’m assuming) can, it saves 95% of the energy needed to make a new one from bauxite, the raw ore.

Electronic waste pile, Birminghoan, AL. Photo: Curtis Palmer, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

At the other end of the spectrum are electronics. Exact figures are hard to come by, but when you recycle a computer, it appears that the energy savings is somewhere between 20% at most, to possibly as little as 1%. Don’t get me wrong, there are good reasons to recycle your tablet and phone rather than toss them in a landfill. Devices like cell phones and computers contain rare-earth metals that are in short supply (which might explain their name), and which take a great deal of energy to extract.

The point is that nearly all the energy used to manufacture electronics goes into making microchips. Processing silicone, along with the need for ultra-pure environments in which to make semiconductors, account for nearly all of the power used in bringing the latest version of your smart phone, which is one micron thinner and ten times as fragile as the last iteration, into your hands. You can’t get that stuff back. It’s like trying to recycle sweat.

The electricity used in making a 30-watt laptop with 2 gigabytes of RAM (i.e., the wimpiest computer available today) would power it for over ten years, assuming eight hours of use per day, seven days a week. Cell phones have similar profiles. This is why it fixing them makes a difference to the planet.

Unfortunately, manufacturers do not make it easy for us. Tamper-resistant screws, glued-on components, fragile components and soldered batteries are more effective than “No Trespassing” signs in terms of keeping us away from the innards of our gadgets. Fortunately, some manufacturers are beginning to read the (as-yet rather faint) writing on the wall, and are making devices more accessible. And there are many online communities dedicated to overcoming these impediments to repair.

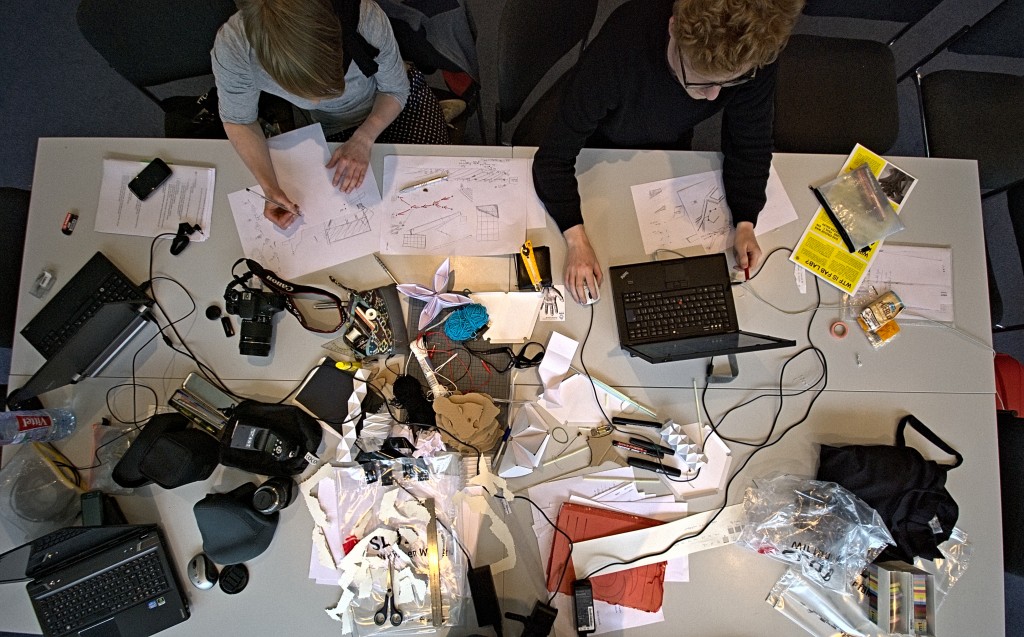

Fixers at work in a maker space. Photo: SLUB Presse2015, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

There is nothing like a real-life fixer, though. In urban centers like Ottawa, some maker spaces involve high-tech resources like 3-D printers, laser cutters, and digital lathes, and may have full-time paid staff. But a maker space can also be a room with a sewing machine and a tool box in a church basement. The critical element of maker spaces is the fixer—people with know-how and experience. While a shop can take care of the problem for you, fixers can show you how. It’s like that old adage: teach a person to fish and they’ll eat for a lifetime. Teaching them to repair a fish is harder, I’m told.

Locally, several organizations are looking toward opening maker spaces, including some public libraries. Maria Corse, director of Deep Root Center for Self-Directed learning in Canton, has been seeking a location for one for the past couple of years. She now has a tiny makeshift-maker space at the center for the youth she serves, and is confident a community-based location will be a reality in the near future.

Currently there is also interest in a regional re-use center. Community organizations such as the Local Living Venture, a group promoting sustainable practices, along with County and local governments, have been studying the potential for one in northern NY. Re-use centers not only save resources, they provide jobs as well as valuable skills training opportunities for youth.

Going forward let’s hope we see more of the good kind of fixers, and that we need fewer of the Wag the Dog kind.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Tags: economy, environment, makerspace, repair, reuse