Will invasive carp take over the Great Lakes?

School of jumping silver carp. Photo: Jason Jenkins, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Asian carp are more popular on social media than most humans. These rather large members of the minnow or Cyprinidae family have taken to leaping from the water to slap anglers upside the head, maybe as payback for using their smaller kin as bait. I’m told YouTube videos of this abound. But it’s tough to capture in a video clip the damage these invasive fish could do to Great Lakes ecosystems.

Though our common carp is native to Asia, it seems to have made peace with our waterways in the 150-some years since it arrived, and these days is behaving. Asian carp is a term applied to a gang of four alien carp species: bighead, silver, black, and grass. These guys are expert in two domains: eating and baby-making.

These carp all eat ravenously, grow fast, and lay from 250,000 to 3 million eggs per year. Depending on the species, they may consume between 20% and 100% of their body weight each day, stripping their environment of plankton, aquatic plants, and invertebrates. When young, Asian carp are capable of doubling in size in one year, quickly placing them out of range of most predators. And while they might improve water quality in sewage lagoons, they make clear water turbid and less suitable for native fish.

Unlike in their native range, Asian carp in North America have no natural controls, and overwhelm aquatic systems. To quote Dan Stephenson, chief of fisheries for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources: “There are more Asian carp in Illinois than in China.” Like the old lady who swallowed a fly, we created today’s big problems by importing Asian carp decades ago to solve various small ones.

Aside from the fact silver carp enjoy rocketing up to thrash boaters, they can in some cases increase the severity of toxic algae blooms. This is ironic, given they were imported to remove excess plankton from water. Silver and the closely related but larger bighead carp are filter feeders, with specialized gills that constantly direct plankton to the mouth. Because they lack true stomachs, nearly half the nutrients they take in are excreted. Certain toxic blue-green algae not only pass through intact, they exit with more food than they came in with. Carp also release nutrients when they feed on bottom sediments. The silver lining would be if these two were awesome game fish, but unless you can get plankton on your hook, you probably won’t catch either.

Black and grass carp, close cousins, both eat proper food. Brought to the southern US in 1963 as a farmed fish, grass carp may eat their body weight each day, devouring native aquatic plants, and increasing the water’s nutrient load in the process. In addition to eating food that native fish need, grass carp pose a threat to wetlands. Black carp, which can attain a length of nearly 6 feet, are the largest of the four, and at the moment, the least numerous. They feed primarily on snails and mussels, but also aquatic insects and worms.

To be fair to carp, it’s not their fault they’re out of control here. Silver carp are a threatened species in their eastern Siberian homeland. And worldwide, they are an important food source. According to the United Nations Farm and Agriculture Organization, aquaculture produces more grass carp—5 million tons annually—than any other fish species.

Grass carp. Photo: Peter Halasz, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Of the gang of 4, only the grass carp is confirmed in the Great Lakes (Erie, Ontario & Michigan), with a known breeding population on the rise in Lake Erie. The other three have made their way up from the Mississippi River to the doorstep of Lake Michigan, thanks to the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, built in the 1800s to send Chicago’s poo down South rather than into Lake Michigan. This canal is the only connection between the Mississippi and the Great Lakes, and has been dubbed a superhighway for invasive species.

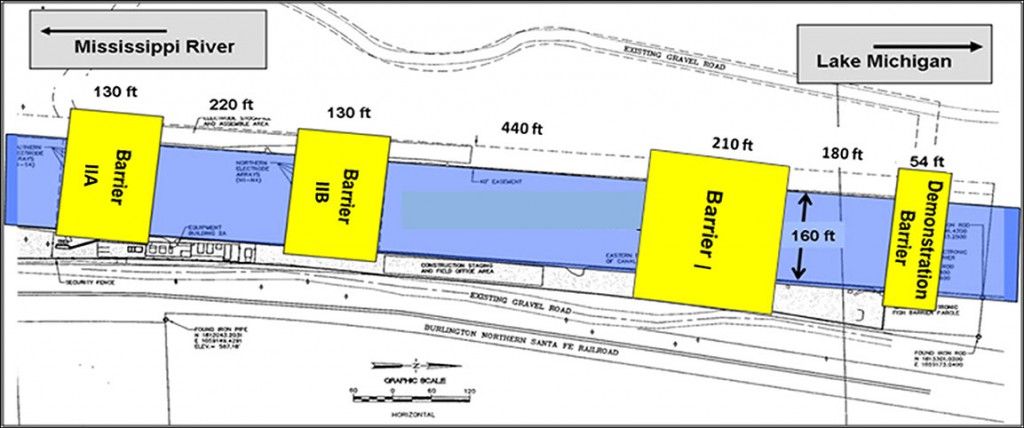

Due to opposition from a few business interests to closing the canal, an “electric fence” barrier was set up to deter invasive species from migrating into the Great Lakes. Clearly it was not enough, because in June 2017 an adult silver carp was caught beyond the barrier, just 9 miles from Lake Michigan. Henry Henderson of the Natural Resources Defense Council has compared Asian carp to cockroaches, because if you see one, it means there are a lot more nearby. Currently, plans are underway for a better electric fence.

Electronic fish barriers in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal were built to try to prevent carp from entering the Great Lakes system. Illustration: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

There is an argument that the Great Lakes themselves are enough to keep out invasive carp. Because the lakes have been so thoroughly filtered by invasive zebra and quagga mussels, the logic goes, filter-feeders such as grass and bighead carp will stay in the more fecund waters of the canal. Therefore, don’t worry—be happy.

Well, that’s an interesting thought, but it leaves out black and grass carp, which eat solid food. We have no idea whether the black carp population would explode when presented with endless fields of mussels on which to graze. Should that happen, the lakes would slowly revert to their pre-1980s murkiness, and the laissez-faire policy on invasive filter-feeders would get blown out of the water.

Time will tell whether the Great Lakes will collect the whole set of Asian carp, or if common sense will prevail, and the canal will be sealed before that happens. I won’t say on which I’d bet.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Tags: carp, Great Lakes, invasive species