We Need A Frontier

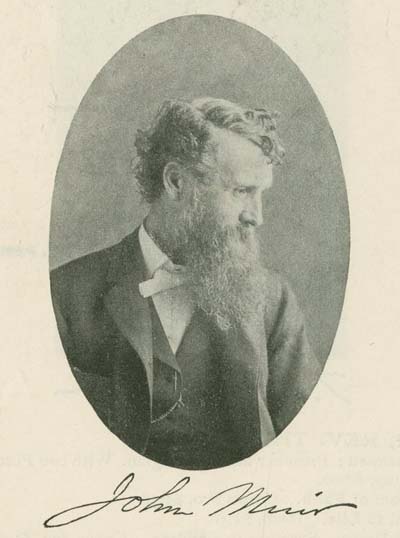

Yosemite National Park turns 122 today, thanks largely to this guy:

John Muir saw redwoods felled to make toothpicks. He couldn’t stand it.

He also wrote about the need – not the luxury, mind you, the need to:

“…throw a loaf of bread and a pound of tea in an old sack and jump over the back fence”

He distilled his awe of western landscapes – and his desire to light out – into an eloquent defense of nature. He wasn’t the first American to say we need solitude. Henry David Thoreau was saying it in the mid-1800s, but it wasn’t a popular sentiment. Maybe because Wisconsin and Minnesota were still frontier lands, where families experienced abject loneliness, fear and poverty trying to carve out a living by literally carving the landscape.

But a few decades later, John Muir turned this thinking into a National Park, then a National Park System.

Yellowstone was first, in 1872 – the same year Verplanck Colvin was granted $1,000 from New York State to survey the Adirondacks.

It wasn’t all lofty ideals, of course. Find a giant park and you’ll find a watershed that needs protection.

Yellowstone and Yosemite safeguard water for Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area. The Rocky Mountain National Park protects the Colorado River. The Adirondack Park preserves water for New York City.

Still, it’s worth noting that Thoreau and Muir and lots more like them were right: we need a frontier. The American mind demands a line on the map that demarcates the known and the unknown. For my generation, that frontier might be outer space. Which is fine, but it never held my interest. At this stage, we’re talking about living in a glorified RV for months just to reach the uninhabitable sands of Mars.

I’d rather go hiking.

And when I do, one of the first things that comes to mind is thanks – to those who had the foresight to draw a line on a map and effectively say, “Not here. You won’t build here.”

“A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

-The U.S. Wilderness Act, 1964

This line of thinking re-routed railroads in the West, it protected forests across the continent and it created a different kind of place. To reach it, you have to prepare: You have to exercise and pack wisely. You might feel some trepidation or unease about a trip to a place where Wi-Fi is spotty (at best), where you’re hours or days away from help and where you don’t know what will happen or what you’ll see.

These are the ingredients of a frontier and they’re also the conditions that give us access to another: our minds, which are certainly “trammeled by man” – or at least pop culture. If we’re to endure 360 days a year of politics, crime stories and Honey Boo Boo (which might be repeating the same thing thrice), then we’d damn well better spend the other five far away from all this sound and fury.

The good news is we can. The wilderness areas in the Adirondacks and elsewhere give us freedom and a way to exercise that part of our brain that craves the unknown.

Go.

The loaf of bread and pound of tea are just stores. You’re the canvas. The wilds are the paintbrush.

Go.