Thanksgiving thoughts…about Indians and settlers

Part of the happy myth: “The Pilgrim’s Party: A Really True Story” by Sadyebeth & Anson Lowitz c. 1931. Photo of 1959 edition by Lucy Martin

Thanksgiving in Canada does not tap into the “first Thanksgiving” story many Americans are raised with. You know, the one where friendly Indians taught the nearly-starving pilgrims of Plymouth plantation how to survive. (Usually involving some combination of Samoset, Squanto and Massasoit, a leader of the Wampanoag.)

The historical record does indicate pilgrims and Indians sat down to a three-day harvest feast sometime in the fall of 1621, though they did not call that gathering thanksgiving.

While verifiable facts are sparse, the image sure feels good: food, family and fellowship enjoyed in peace.

Since all our relatives are in the U.S., my husband and I typically treat Canadian Thanksgiving in October as a three-day weekend to go exploring. Hence, we were cycling the Tay Shore Trail near Georgian Bay on that holiday last month.

Our visit included a stop at something called Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons. It’s a re-creation of an actual Jesuit missionary outpost which was established in 1639. Inter-tribal warfare forced the Jesuits to abandon the site ten years later. During this general time span, some of the Jesuit priests were killed by Indians (most often by the Iroquois) as interlopers who brought disease and changes that threatened existing ways of life. (An arguably accurate assessment.)

At Sainte-Marie I spoke with Joël Mayotte as he played the role of a donné, or volunteer lay brother. (A derivation of the French verb donner “to give.”) Mayotte was serving up three sisters soup to all who passed through. You can hear our conversation here.

Reconstructed buildings and a site map of Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons, depicting a mission in the 1640s. Photo: Lucy Martin

Mayotte graciously took extra time to detail more of the back story. But even at a historical site, history is not everyone’s favorite topic. Which is why he had to curtail the serious subject of the Jesuit martyrs to ladle out more soup!

Some visitors to the cookhouse were history buffs. One man mentioned fuzzy recollections of a recent book that he thought was about Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons at that time – “The Orida, Orinda…something like that.” I knew the author, but not that title. So I made a note to go find it later.

My husband thought we were on a pleasure trip. So I turned him loose while I hurried through the rest of the site and the small museum there. Alas, it only skimmed the surface.

That’s the reason for this post – there’s always more to discover or think about. And Thanksgiving is a rare time when non-natives bother to recall other people lived all over North America first.

For instance (once again/as usual!)… Huron is not the correct name for the people in question. Huron was what the French called that tribal group, supposedly because the hairstyle (or headdress?) reminded them of a breed of bristle-back hog. Lake Huron, then, should perhaps more properly be Lake Wendat.

It took us over 5 hours to drive to Georgian Bay from Ottawa on pretty good roads. Our car whipped past the original highways of the land: many, many lakes and rivers. It would be a long, arduous journey by canoe, which is how natives, fur trappers and Jesuit missionaries got around. This is not news. But it’s humbling to see and consider how much physical endurance ordinary life used to demand.

In no particular order here are a few other things I am still mulling over after our stop at Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons.

First Nations people (the Canadian term) – or Indians – were skilled and tough. Early European settlers were tough too, but they had much more to learn. The smartest settlers paid heed to acquiring native knowledge.

Today we tend to view the whole sorry saga of what happened to North America’s first inhabitants with 20-20 hindsight, knowing it mostly ends badly for the natives. But in the 1600s, it was really anyone’s guess how things would turn out. For a long time, in many fights, the whites would have been on the losing end.

I did find and read the book mentioned at Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons. It’s called The Orenda, by award-winning author Joseph Boyden. If you like history-based fiction or are interested in that period of settlement, I highly recommend it. The novel is said to be exhaustively researched, which I hope means it is fairly accurate.

I do wonder how one can ever really know the lives and thoughts of pre-contact cultures. We frequently depend on the written record – and there’s often lots there, including the Jesuit Relations – correspondence and records from the actual time and place. But that’s just one side, slanted by inevitable cultural bias. Left undisturbed, tribes would still know their own culture and history. And some have managed to keep both. But so many were torn asunder – made to forget and reject – that much has been lost.

Anyway, here’s more about The Orenda to wet your appetite. A review for the Globe and Mail, by Charles Foran: “Joseph Boyden mines Canda’s bloody past for surprising spirituality.” The Toronto Star’s Andrea Gordon has this engrossing interview with Boyden about the particulars of this book:

Set in the Lake Huron region where Boyden’s family spent summers boating and camping, The Orenda is told through the eyes of three narrators whose lives become entangled following a brutal encounter. Bird is a Huron elder and warrior, Snow Falls is the Iroquois girl he kidnaps, and Christophe is a French Jesuit missionary loosely inspired by the historic figure Jean de Brebeuf.

“No one is bad and no one is good in this novel,” says Boyden. “They are all complicated people.” And each has their share of humanity, heart and treachery.

It’s a good read and a useful mental exercise to get into the head-space of three different cultures. Boyden had to wrestle with how much torture to include and how to frame its significance. Again, Boyden speaking from the Star interview:

Those scenes are also hard to read. But “if I was going to properly capture this time period and all of these peoples, the violence had to be incorporated because it was part of the culture.”

“The Christians tortured their victims to demean and to belittle and to ultimately punish. The Huron and the Iroquois tortured one another to honour and to try to possess the great power they saw in one another.”

After finishing The Orenda, I was left still thinking about diverse topics.

Belief systems are very, very powerful. We aren’t always capable of understanding ones different from our own. Especially ones with completely divergent foundational beliefs. Case in point, the Jesuit priest in The Orenda is dismayed by the native belief that all things have spirit. In debating this point a native wise-woman retorts the Christian view is in grossly in error, because: “… there is nothing in the world that needs us for its survival. We aren’t masters of the earth. We’re the servants.”

Of course, Jesuit missionaries, (some would say all Christians) were/are compelled by scripture to share their faith and win converts. (Because salvation through accepting Jesus is better, or more important, than any other way of life.) Meanwhile non-believers find many parts of Christianity quite nonsensical. I know, this all sounds like “duh!” stuff! But Christianity has lost much of the pure power it once held over people, institutions and governments. I think we do forget what a formidable cultural force it was in centuries past.

Many did follow that path for selfless reasons, an argument that could be made about the North American Martyrs.

Some remains of St. Jean de Brébeuf and St. Gabriel Lalemant were buried here, at Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons. Their bravery under torture was admired by their Iroquois captors. Photo: Lucy Martin

Consider this quote from Catholic Online:

When St. Isaac Jogues was received into the Jesuits his superior asked what he desired. His response: “Ethiopia and Martyrdom.” “Not so.” was the reply. “You will receive Canada and martyrdom.”

Seeking fatal martyrdom is out of vogue in the west. These days that degree of devotion is viewed as as creepy excess. But there was a time when that was the height of bravery, devotion and selflessness. And other types of martyrdom are still respected, as seen quite often of late in what we call terrorist attacks. (I am not defending suicide attacks, or comparing priests who die while trying to serve with those who die trying to kill others. I’m just remarking on the power of different belief systems that drive such actions.)

Researching the topic of early colonial settlement I found a webpage that spoke on two other topics quite well – conflict and torture:

Many of the Indian tribes were hereditary enemies of one another. An early French expedition, headed by Samuel de Champlain, founder of Quebec City, “Father of New France,” was with a group of Huron Indians when they were attacked by an Iroquois war party. Champlain and his men, using their muskets, drove off the Iroquois, killing many, and from that time on the Iroquois were anti-French (and therefore, when the occasion arose, pro-British), while most other tribes of the area became pro-French and anti-British. This was relevant in subsequent struggles between the British and the French, and later between the British crown and the American colonists.

Many of the Indian tribes placed extreme value on courage and hardihood, as demonstrated by the ability to endure pain without flinching; and so the practice of torturing prisoners taken from other tribes was a kind of competition, in which a prisoner upheld his tribal honor by showing no sign of pain, deriding the tortures that he was undergoing, scorning his captors for a lack of imagination, and assuring them that his discomforts were mere fleabites compared with the tortures which his tribe had invented, and stood ready to inflict on his captors once the tables were turned.

Getting inside different world-views as they collide is a great strength of The Orenda. Everything each faction does makes sense, even as the three groups strain (and often fail) to understand the other.

We pretty much know how the rest of the big picture played out: The French lost Canada to Britain. After which, on the whole, natives gradually lost the continent to Europeans and their heirs, the Americans. For some, the fourth Thursday in November should really be a day of mourning. This report on annual Thanksgiving demonstrations at Plymouth by Democracy Now contains another view of natives worth considering: “We are not vanishing, we are not conquered.”

Wendat (Huron) pottery circa 1600-1649 A.D. on display at Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons. Photo: Lucy Martin

But going back to the 17th century, after their rout by enemy Iroquois, I was curious: what happened to the rest of the Wendat? It would appear that some descendants now live in (wait for it!) …Kansas! Here’s more from the Wyandot Nation webpage:

The Wyandot Nation of Kansas is made up of the descendants of Wyandots formerly known as “absentee” or “citizen class Wyandot Indians. We called ourselves Wendat, meaning People of the Island. However, the French explorers and traders called us “Huron” which may have referred to the roach headdress worn by Wendat men. Our ancestral homeland is considered to be the area around Georgian Bay, an inlet of Lake Huron. Due to war and disease our people were forced to disperse; one group went east to Quebec the other south to Ohio, Michigan and Ontario. The name Wendat was Anglicized to Wyandot / Wyandott / Wyandotte while we were in Ohio and Michigan. In 1843, the Wyandots were the last of the Indian Tribes to leave Ohio and relocated to Kansas.

Even more specific information is available on that site, including details about Wendat in modern-day Ontario – before they were forced out, that is.

If you’d like a more uplifting view of Thanksgiving in terms of re-claiming what the holiday could be, consider this 2012 Huffington Post essay by Rev. Dr. Randy S. Woodley:

As America’s Host People, Native Americans are the keepers of the land, that is our sacred duty. Our responsibilities include bringing the land, the people, and the rest of creation back into harmony. Traditionally, we have done this through prayer, ceremony and special festivals. If we are willing, Thanksgiving can be a time of reconciliation and healing of the land. Even though everything within us should compel us to do otherwise, we must begin somewhere. We cannot hate, or even ignore one another and expect to heal the land. By thanking the Creator and showing love to one another, we can actually begin restoring harmony in the land. It can begin with a simple meal.

Something to consider beyond ample servings of turkey and pumpkin pie.

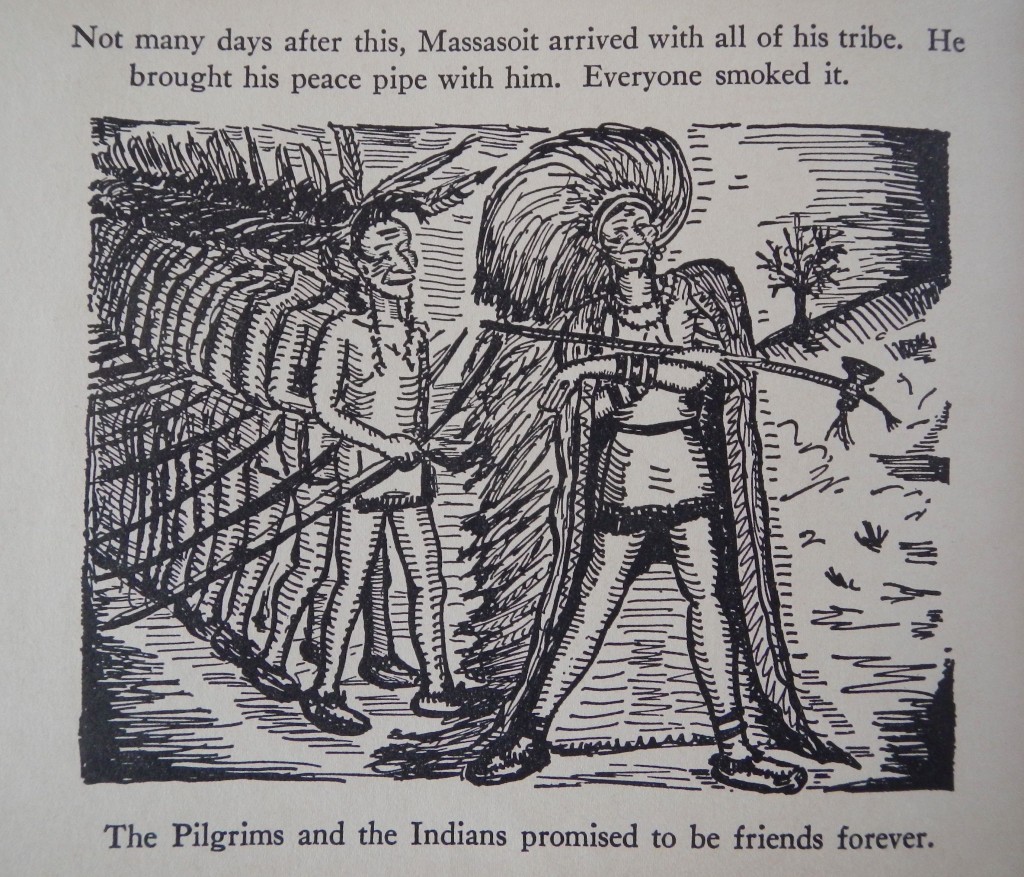

In this page from the already-mentioned children’s book “The Pilgrims and the Indians promised to be friends forever.” Photo: Lucy Martin

Tags: canada, history, Jesuits, Joseph Boyden, National Day of Mourning, Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons, Thanksgiving, The Orenda, Wendat

To be fair, it is challenging to pick sides in events at the early stages of contact. In 1615, the Huron leveraged New France to attack Iroquoia in what is now western NY sweeping down and around the Kingston area: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_de_Champlain#Military_expedition

They failed but set events in motion. The Iroquois only get access to western arms in around 1648-49 from the Dutch in Albany to counter the support given by New France. Both empires, the French and the Dutch, are behind these alliances and conflicts in their efforts to control the fur and pelt trades via the rival St. Lawrence and Hudson valleys. Both have mixed commercial and evangelizing interests, Protestant and Catholic. The same battle is occurring at the same time in the Caribbean between the Dutch Protestant empire and the Spanish Catholic one. In each case, each western culture is playing out the dual interests of gold and God.

You might want to check out a fairly recent film: Black Robe, about one French missionary’s effort to convert the indigenous. It’s in French with subtitles.

I just watched something called Black Robe, but it was made in 1991. Same one? Beautiful scenery and pretty well done.

Strictly by coincidence (it was on the shelf at the library) I just finished watching Crooked Arrows (2012). It’s your standard “underdog sports team goes all the way” flick, but this one is about lacrosse and its cultural/spiritual origins. Fun movie! Check it out if you like lacrosse or would like to see a movie that tries respect host cultures more than usual. (The bonus features on the DVD are excellent, be sure to watch them too.)