Stories, brains and cultures

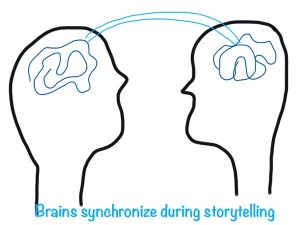

Graphic: bgblogging, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

It would be easy to assume that because NCPR is in the news business, that we are in the data business, the fact business. But actually, we are primarily in the story business. More, I think, than in most media, radio reporting is storytelling. A scene is set, characters are introduced and speak, a narrative arc is created along a progression of time, and a resolving point is reached.

Data–facts–flesh out the story, but the radio news story shares its skeleton with fairy tales, memoirs and epic poetry as well as non-fiction. What separates the story from the experience is the inclusion and exclusion of various elements so that coherence is achieved amid the clutter of reality.

Neuroscience posits that this is how our brains actually work with the data they receive. In Your Storytelling Brain, Jason Grots says:

“Cognitive science has long recognized narrative as a basic organizing principle of memory. From early childhood, we tell ourselves stories about our actions and experiences. Accuracy is not the main objective – coherence is.”

The theory is known as “narrative identity.” A Wikipedia entry defines narrative identity in this way:

“The theory of narrative identity postulates that individuals form an identity by integrating their life experiences into an internalized, evolving story of the self, which provides the individual with a sense of unity and purpose in life.”

So storytelling puts information into the same form in which the listener’s brain will use it. In a NY Times article, Your Brain on Fiction, Annie Murphy Paul says:

“The brain, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life; in each case, the same neurological regions are stimulated.”

Stories can have a similar effect on groups, shaping widespread attitudes through vicarious experiences. A common set of stories shared among large numbers of people is one of the binders that define a culture. Our world view may be held largely in common with those who have absorbed the same stories about the world that we have. For example, the assassination of JFK 50 years ago is a story that has burrowed deep into the DNA of American culture. Among those of us of a certain age, shared stories of that experience form a reliable touchstone.

Recognizing this connective effect, one fear that many have about the new era of media fragmentation is that fewer of us will hold the same stories in common, leading to an ungluing of our culture. As similar sets of data are used to generate competing and conflicting stories about the world, our recognition of who the “we” in we actually is will change and become increasingly exclusive.

Others take the same set of facts and see an unfolding story of richness and diversity that will lead to a more nuanced and sophisticated view of who the “we” in we actually is.

Which story do you buy? Let us know in a comment below.

Tags: listeningpost

I struggle with this very question (when I have time). I just don’t know, nor do I think ANYONE really knows, how current info-gathering will affect “us” as a nation. None of us can predict the future.

I am “of a certain age” (how did THAT happen?) and can understand how media can be the glue that holds us together. Important events in the world were reported by a handful of responsible reporters, and we all listened and trusted what they had to say, felt connected to the story.

With all the outlets available now, I don’t think there can be a coherence anything like what it was before. I don’t know what that means, anthropologically speaking: We can only wait and see.

Unflinchingly, I buy the second story, and I can’t think of any better words than the two you used: nuanced and sophisticated. The beaucoups options I have from which to choose my storytellers is inspiring, and the very fact I have access to different stories off the same set of facts is what I like about our current media. When those differences lean toward the subtle it really becomes interesting.

A classical music analogy just appeared to me: that of two orchestral conductors performing the same piece. Sometimes the difference is not so subtle, but with another pair of conductors, I find the interpretation I prefer would be a combination of the two performances.

As I recall from my “Cultural Anthropology”, an elective forced upon me by the engineering department at CU, anthropologists are relatively confident that long before the invention of writing homo sapiens passed along their accumulated knowledge and culture via story and song. Those whom had a knack for both undoubtedly benefited from them and were more likely to survive long enough to procreate thereby endowing those of us who followed to be born with instinctive/innate tendencies to sing and or tell stories and thus perpetuate our histories.

Today’s modern songs are, for the most part if we ignore Opera, very short in comparison to the ballads of old; however, the advent of writing has certainly opened up story telling.

What do you mean WE, kemosabe?

Humans have always struggled with the me vs. we dilemma.

We want to belong but we are afraid of losing ourselves. I think this is especial true for Americans who like to view themselves as individuals.

We take the plunge into the vast ocean of the we when we think we have a better chance at survival if we submit to being part of a group than we would if we go it alone. But even when we take the plunge, it is still about us as an individual.