“Noah” takes Christians to the deep end of the pool

“Noah,” starring Russell Crowe, is being marketed as a kind of action-disaster movie — think “Gladiator” meets “Armageddon.”

“Noah,” starring Russell Crowe, is being marketed as a kind of action-disaster movie — think “Gladiator” meets “Armageddon.”

And on its face, the Great Flood story from the book of Genesis seems like a made-for-the-big-screen epic.

It’s a life or death struggle played out on the widest possible scale, as humanity struggles for survival.

Expect big special effects and pounding music as the storm clouds gather. (See the official trailer below)

The problem, of course, one that Christians have struggled with for centuries, is that in this particular action-adventure story, the “bad guy” of the great myth is a guy we thought was on our team.

It’s not Sauron or Satan or Loki or some other Voldemort dark-lord villain that’s out to destroy the world. It’s God. You know, as in, the Father. The Maker of Heaven and Earth and Us.

“I will blot out man whom I have created from the face of the land,” He declares, “for I am sorry that I have made them.”

In the movie version, Russell Crowe looks mournfully into the camera and says, “He’s going to destroy the world.”

The morality of this pronouncement — the lack of morality, rather — is stunning. Imagine a father deciding to give up on his children, deciding that they are so far beyond redemption that they deserve death.

Hard to swallow, right? In the centuries after the Old Testament was written, we humans developed ideas about ethics and justice and forgiveness that soundly reject the concept of collective punishment, of blood debt, of cleansing by genocide.

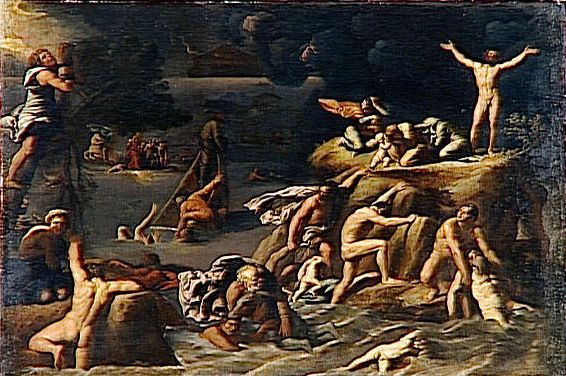

So the idea of God literally drowning every man, woman and child on the planet takes one’s breath away. Actually, taking breath away is exactly what He intended.

“I am bringing the flood of water upon the earth, to destroy all flesh in which is the breath of life,” God promises, according to the text. “Everything that is on the earth shall perish.”

God decides, of course, to save Noah’s family and a collection of animals.

But the story still describes an act of murderous rage which great thinkers and poets and theologians have grappled with for centuries without much success.

“Perhaps during the great flood God in His mercy put men to sleep,” suggested the great Portugese writer and Nobel laureate Jose Saramago:

So death might be gentle, the water quietly penetrating their nostrils and mouths without suffocating them, rivulets gradually filling, cell after cell, the entire cavity of their bodies. After forty days and forty nights of sleep and rain, their bodies sank slowly to the bottom, at last heavier than the water itself.

But in his effort to soften the idea of God’s murderous wrath, Saramago instead captures the horror of a creator god snuffing out an entire planet’s beautiful creatures.

Bill Maher, the atheist and professional pot-stirrer on religious issues, won headlines earlier this month by arguing that the Noah story — and the new film — cast God as a “psychotic mass murderer.”

His language was crude, bitter and carefully crafted to spark controversy. But I suspect that Maher is on to something in questioning a part of Christian cosmology that causes even many devout Christians to blink.

“He sent a flood to kill everyone — everyone,” Maher pointed out. “Men, women, children, babies. What kind of tyrant punishes everyone just to get back at the few he’s mad at?”

Here’s the full segment from “Real Time with Bill Maher.”

As critics will point out, the Noah story is only one of many Biblical tales in which God does things — and demands things of his followers — which strike modern readers as brutal, barbaric, even evil.

But of course, that’s simplistic. The Christian God is not a psychopath.

But neither is he a Sunday school shepherd. There are veins of darkness and terror in Scripture that are every bit as frightening as the veins of light are hopeful.

I think it’s fair to argue that this thorny aspect of the Judeo-Christian tradition is part of what is emptying church and synagague pews, in Canada, Europe — and increasingly here in the United States.

Even as many progressive and moderate Christian leaders work to repackage their faith as a fun, relatively unchallenging “lifestyle choice,” there remains at the heart of Scripture an often painful and and troubling cosmology.

This latest treatment by Hollywood probably won’t do much to help American Christians wrestle with all that.

“Noah” won’t shine much light on how these ancient texts match — or don’t match — our modern sense of justice and goodness.

But I’m guessing more than a few movie-goers, especially more casual Christians who haven’t read their Bibles, will leave theaters in the coming weeks scratching their heads.

They’ll be asking who the bad guy was in this film and maybe asking new questions about the sometimes very angry and jealous and frightening God at the heart of their tradition.

.png)

It’s a Bible story. It is not an historical story. It’s a story in the same vein as Adam and Eve being kicked out of the Garden of Eden and Job being put through living hell because of an argument between God and Lucifer. It’s a morality play.

The problem here is the result of humans trying to imagine God as though God were human which, of course, God is not.

As God was said to have said to Job after Job survived the test put to him as the result of God’s discussion with Lucifer, “My thoughts are not your thoughts. My ways are not your ways.”

The stories in the Bible are more about human frailty than they are about God who is essentially beyond human comprehension.

What’s interesting about the Bible, Pete, is that it gives a very detailed, complex description of God — and you’re right, in a way it is a morality play.

What’s complex, though, is that this morality play leaves us with very troubling questions about the nature of the morality on exhibit.

Your reference to Job is a great example. In the Book of Job, God does — or allows done — truly horrible, awful things to an innocent man in order to test his obedience and faith.

And God’s basic explanation, after murdering Job’s family and destroying his life without cause, is, “I am infinitely powerful and complex and you have no right to question my behavior.”

It’s a moral argument that Job eventually accepts. But it’s not one that sits comfortably with many modern readers.

Brian, I have long thought there is a human mistake in the Bible. It’s the one that says man was made in the image and likeness of God. This is actually a very old pagan idea. You see it in Greek and other mythologies. In my view it is we who have created God in our own image and as a result, we attach human qualities to God.

I don’t view God as a moral entity. Morality can only exist between equals and we are certainly not equals with God. God’s natural laws do not care who you are. The sun shines on the just and the unjust. Neither a bullet nor a hurricane care if you are a good person or a bad person.

People need to stop worrying about God’s morality and look to their own.

If one insist on looking at the story of the flood, what one should learn is that Noah was smart enough to build an ark. Job was smart enough not to blame God for his problems and was just grateful to have weathered the bad times and move on. Blaming God for things is only one of the many ways we use to make ourselves feel more important than we are.

As an atheist, I find Bible stories meaningful as deeply observed portraits of our relationships with each other and the world. Moving the spotlight away from God and onto the human protagonists allows me to identify with their struggles and consider how I would react in similar circumstances.

(This is not always true -there are some Bible stories that just don’t make sense. See Samuel 6:4 where the Philistines are exhorted to make an offering to God of five golden emerods and five golden mice. Now, I don’t know about the mice but I sure am wondering what He wanted with gold hemorrhoids!)

In some ways I agree with Pete – we don’t need to figure out why God wanted to wipe out the human population. He just did.

In reality, it’s a deus ex machina device (!) to get us to the meat of the story. What we care about is how Noah rose to the occasion, working for the survival of his family and every living creature he could get his hands on. We identify with his vulnerability, his terror and also with his compassion and resourcefulness. It is one of the more comforting Bible stories in that Noah and everyone he cares about makes it through the flood. That’s probably why children love it so much.

If, like me, you don’t think of morality as divinely inspired, you don’t need to worry about whether God acts justly or not, you simply need to look at whether you are acting justly. From this standpoint, the story of Noah has a lot to offer when we consider our responsibility to the future of the planet.

Pete says: “Morality can only exist between equals and we are certainly not equals with God. God’s natural laws do not care who you are. The sun shines on the just and the unjust. Neither a bullet nor a hurricane care if you are a good person or a bad person.”… “People need to stop worrying about God’s morality and look to their own.”

And (allegedly) Jesus said “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect.”

Matthew 5:47-48

Adam and Eve allegedly ate from the tree of knowledge giving them and their progeny the ability to distinguish between right and wrong (morality, or correct behavior) and be like God (except for everlasting life). So apparently if the perfect God does these things God’s behavior is a pattern we humans should follow in order to be likewise “perfect”. By that logic all notions of compassion are wrong. We should be brutal and uncaring whenever it strikes our fancy.

what in hell is an emerod? and why do I need five?

I guess the fundamental question is what is at the heart of CHRISTianity: the Bible or Jesus CHRIST? Most of the fire and brimstone stuff comes in the pre-Christian Old Testament.

Brian (MOFYC)

I don’t think most theologians would be comfortable with that argument. Jesus Christ is, after all, the guy who according to the New Testament will separate the wheat from the chaff.

And in the context of the Gospels, it’s pretty clear — and most Christian thinkers through history have pretty much assumed — that most humans on earth will fall in the latter category.

There are some parts of the Old Testament that aren’t echoed in the New. But the Noah story is of a fairly consistent piece with the larger cosmology (and morality) of both books.

Brian, NCPR