When we didn’t eat grapes

From somewhere between the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s no one in my family or circle of friends bought grapes.

Why? Cesar Chavez.

The United Farm Workers co-founder was successful in using a boycott of grapes to raise the national consciousness about migrant worker conditions. He was so successful that grapes became a “tainted” fruit for many of us even years after the boycott ended (it was certainly over by 1970). In truth, there’s a little bell that goes off in my mind even today whenever I purchase grapes. The bell signals this message: it’s okay, the boycott is over, you’re not a bad person for buying grapes.

A new movie based on the life and work of Cesar Chavez is being released this week. Like his contemporary social activist, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Chavez made personal and professional mistakes. And, like Dr. King, the flaws made the man more human, more approachable, and ultimately more admirable. Neither was a saint; both were extraordinary–and ordinary–men.

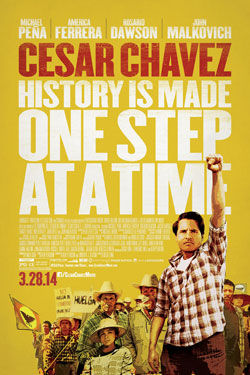

Here’s the trailer for the movie, directed by Diego Luna and starring Michael Pena, with John Malkovich, America Ferraro, Rosario Dawson and Wes Bentley:

With the publicity around the recent 50th anniversaries of the 1963 “I have a dream” March on Washington, and of the assassination of President Kennedy, the release of “Cesar Chavez” recognizes another piece of the social drama that was being acted out during the 1960s.

While I haven’t yet seen the movie, the cast is strong and the reviews are generally positive. More importantly, this reminder of the struggles of migrant workers got me to thinking about today’s labor landscape.

By the early 1980s, a decade before Chavez died in 1993, the United Farm Workers membership had dwindled to less than a third of its 50,000 peak in the 1960s. Through the next few decades, union membership nationwide dwindled to an all-time low, at least since the earliest days of the 20th century when labor was first organizing itself to bargain with management.

In 2014, the complex challenges facing the American labor force include a loss of jobs to globalization, mechanization, and, to some extent, dis-organization. In the face of these conditions, how can labor bargain for better wages or benefits or working conditions? Make no mistake, some industries still employ people in appalling environments–think, for example, about the mega-poultry processing world or the questionable agricultural work settings still plaguing many migrant workers.

I am not trying to imply that labor unions during their 20th century heyday operated without fault. Part of the reason membership dwindled was the entrenchment of bad practices and abuses in unions themselves. But if you trace American labor history from 1900 through 2000, unions played a leading role in creating our nation’s middle class. The diminishing union impact in the automotive, transportation and construction industries has directly paralleled the decline of the middle class and the expansion of the chronically under- or unemployed.

The United Farm Workers story under the leadership of Cesar Chavez was an important and compelling chapter in U.S. labor history. How many other labor actions–whether strike or boycott–so effectively engaged millions of Americans in an act of collaboration–removing grapes from dinner tables across the entire continent for five or more years? Pretty amazing.

Tags: agriculture, arts, cesar chavez, culture, history, labor, movies

I have never not ate grapes and I have never boycotted anything.

I simply don’t believe in boycotts or sanctions or any of the other feel good forms of protest.

Pete: The remarkable thing about the UFW grape boycott is that it worked. The other stand out example of a boycott leading to social change was the Birmingham bus boycott (led, at least for publicity purposes, by Rosa Parks). That boycott directly changed the “back of the bus” Jim Crow practices.