Seeing Selma with Margaret

We know it takes the eyes of a newcomer or a child to see the familiar differently, freshly. Maybe it’s the Main Street in your town, a visitor looks up and sees the elaborate stone carving you never noticed. Maybe it’s your young daughter, looking closely at the dandelion gone to seed, saying, “This is my favorite flower.”

We know it takes the eyes of a newcomer or a child to see the familiar differently, freshly. Maybe it’s the Main Street in your town, a visitor looks up and sees the elaborate stone carving you never noticed. Maybe it’s your young daughter, looking closely at the dandelion gone to seed, saying, “This is my favorite flower.”

The opposite is true, too, of course. Those who know a place or a piece of art or a community better than we do can take us deeper into the meaning of the thing.

For decades, I’ve been the “wheel her in” civil rights activist because of my participation on the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march and with civil rights groups in Harlem, where I went to college. I’ve talked to college and high school classes, to community groups, and offered commentaries on the air. I was a teenager when I walked that highway in Alabama; most memories of those days faded and colored by fear.

There are single moments I remember clearly—buying a frosty Coke from a chest cooler in front of a black-owned country store; being tear-gassed in the yard of the black school we were relegated to by a white sheriff; talking with Stokely Carmichael, who had gone to high school in NYC; standing for a few moments near Dr. King and being surprised that he was shorter than me. But no continuous narrative remains. It was brief: I took a bus south, I spent three days on the march, I headed to Mobile to work on a civil rights newspaper. I was back in school a month or two later. Fifty years ago.

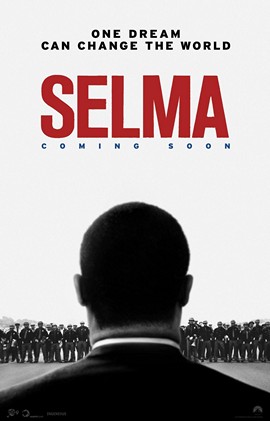

I knew from the first moment it was released that I would, of course, go to see the movie “Selma.” I wanted to see how Ava DuVernay, the young African-American woman who directed the film, saw those times. I asked my friend Margaret Bass, a SLU professor who is black and grew up in the Deep South, to go see it with me.

We agreed that it was interesting to see what the young director chose to include and leave out of the movie. Paraphrasing Margaret, “It’s all important, because young people don’t know. Telling any part of it is important.” The revelation of seeing “Selma” with Margaret was her visceral reaction. Paraphrasing again, “People don’t know how bad it was. It was bad. It was very bad.” She shook her head back and forth as she said these words and I knew she was back in the fear and violence and repression of the segregated South.

Regardless of how it tells the story, this movie, made by a woman who was born at least a decade after the event, reminds us of how hard it was to achieve what we now take for granted. Margaret reminded me that we aren’t there yet—drawing a line between Selma and the shooting in Ferguson.

Across the Pettus Bridge, first attempt to leave Selma for Montgomery. From the Selma history project.

The movie underscored the determination and courage of those who led the movement—those in the strategy sessions in church basements, and those who put their bodies in harm’s way. I think this would have been the key takeaway for me had I seen the movie without Margaret.

Instead, with all the talk about Selma because of the movie, what I hear and feel is Margaret saying, “It was bad, it was very very bad. People just don’t know.”

Don’t worry about Academy Awards and media talk around the movie. Just see it. This is our history, history lived and made by real people, from Dr. King to Margaret Bass. The bullets were real, the stakes made a difference to millions of Americans. The people in this movie–and all those who walked or stood their ground, nameless and unknown–are among our greatest national heroes. They led all of us from what we took for granted towards what is possible.

Alabama State Troopers guard the capitol building as marchers arrive in Montgomery. Selma history project.

Tags: civil rights, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Montgomery, Selma March, Selma movie

“This is our history, history lived and made by real people, from Dr. King to Margaret Bass. The bullets were real, the stakes made a difference to millions of Americans. The people in this movie–and all those who walked or stood their ground, nameless and unknown–are among our greatest national heroes. They led all of us from what we took for granted towards what is possible.”

And you’re my hero too, Ellen.

Thanks, Knucklehead. I feel humbled and teary-eyed. Not easy to accomplish when it comes to this touch old gal.