Who’s shooting holes in the maple leaves?

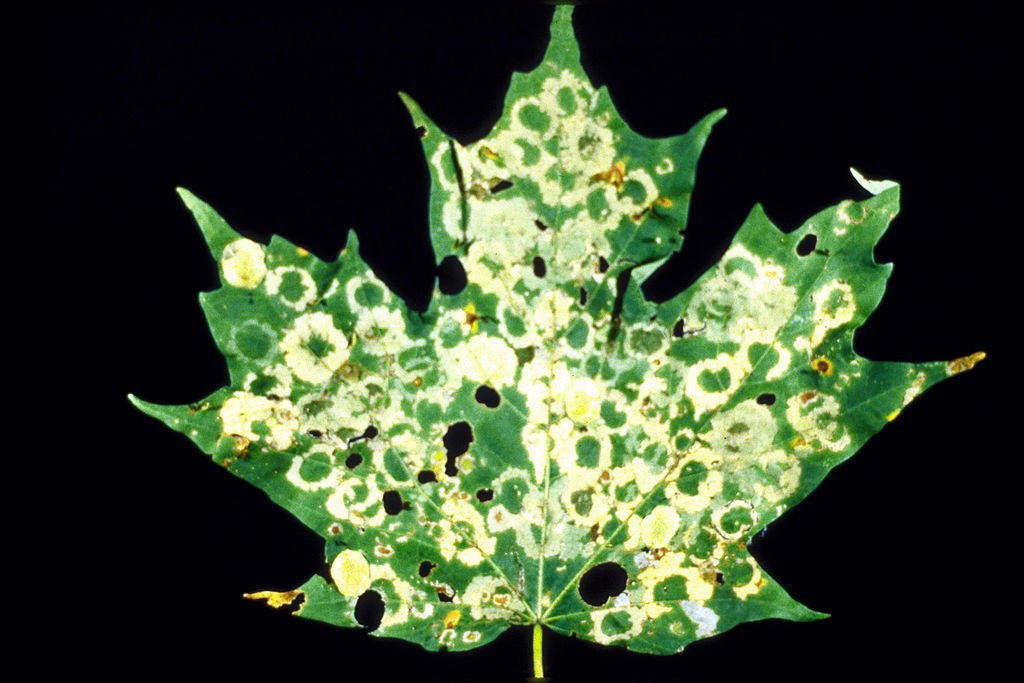

Damage from maple leafcutter larvae (Paraclemensia acerifoliella). Photo: E. Bradford Walker, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Only a joker would argue that plant breeders have secretly crossed our beloved sugar maples with Swiss cheese, but given the way this year’s maple leaves are riddled with mysterious holes, it almost seems a plausible explanation. Beginning in August, near-perfect circles of leaf tissue have gone missing from sugar maples, and from other trees to a lesser extent, as if swarms of Hole-Punch Fairies had gone berserk.

In addition to holey-ness, leaves also exhibit circular brown patches, and by September some had turned entirely brown and fallen off. What’s actually going on is that the maples are moth-eaten. It sounds like another joke, but it’s true. The maple leafcutter (Paraclemensia acerifoliella) moth, a tiny insect that is rarely noticed, is a native pest with a steel-blue body and a bright orange head, although I could probably say anything once I’ve told you it’s hard to see.

When they first hatch in mid-June, leafcutter larvae burrow into maple leaves and begin “mining” tissue between the upper and lower epidermis, or skin, in a circular pattern. This does not produce holes, however. Larvae, which are infinitesimally small (OK, slightly larger than that but not much) at that point, do minor damage in the miner phase, and in fact their burrows are difficult to spot.

Once the wee caterpillars are big enough to “run with scissors,” they use their sharp mandibles to excise rounds of leaf tissue. They then combine two of these discs to use as a protective case. In the words of Douglas C. Allen, Professor of Forest Entomology at SUNY/ESF, they are “a moth with a mobile home.”

The case protects them as they feed on the leaf in a manner known as skeletonizing, consuming all green tissue between veins, and when they move to another part of the leaf they leave behind a round scar. This feeding causes more significant damage than does the leafminer stage. In September when they are mature, leafcutter larvae descend to the ground, carrying their homes with them, and wriggle into the topsoil to pupate. Leafcutters finally leave their homes when they emerge as adults in spring.

Maple leafcutter damage has been noted since the 1850s, with significant outbreaks in New York State in 1911, the early 1920s and in 1997; the mid-1970s in Vermont and New Hampshire; and 1981 in both Vermont and Ontario. Some infestations spanned a number of years, in a few cases more than five. The current outbreak was first noticed last fall by several sugar bush operators and became more widespread this year.

Because the majority of leafcutter damage occurs late in the season, Cornell’s Department of Natural Resource bulletin states: “Sugar maple apparently is more resilient to defoliation by the leafcutter than to that of other insects, probably because of its unique feeding behavior and late-season feeding.” In general, leaf damage that occurs from August onward is of little consequence because trees have already produced more than adequate amounts of sugars for the season.

But leafcutter populations can remain high for several years in a row. Since they start doing some damage in June, repeated severe infestations can affect tree vigor and reduce sap sugar content. Cornell’s bulletin explains: “Studies in Vermont indicated that 3 years of complete defoliation by this insect were required to significantly reduce the starch content of maple roots (an indication of physiological stress).”

Because they are always either fully inside a leaf or a “mobile home,” insecticide treatment is not effective against leafminers. Homeowners and maple producers are encouraged to do what they can to support the health of their trees, like supplemental watering, appropriate fertilizing based on soil tests, and keeping equipment out of the woods when the soil is wet.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Probably some gun nut defending himself against leaves falling on his head.

There is a very short time in the spring, just as the leaves come out, and before they reach full size, when you can actually find a perfect leaf. You’d better hurry though because a million critters start their work in earnest, and grow bigger and hungrier every day. By late summer there is no such thing as a perfect, unscathed leaf.

As my wife says, “everything eats”.