Letters Home: A Gringa in Costa Rica, pt. 2

Part Two – Heliconias Lodge – Sign language and the dumb Gringa

It is very uncomfortable to be speechless. I often make money by writing strings of words and I can fumble my way through a conversation in French or Japanese, but I do not know Spanish.

The staff at Heliconias Lodge have varying reactions to this problem. Luz, the cook, fires off long volleys of rapid Spanish, getting faster as she gets more frustrated with the stupid Gringa. Edwin, the boss, looks like an aging cowboy and speaks in short slurred sentences that even Spanish-speaking Helder finds difficult to understand. Adriel arrives in the morning on his motorcycle and has some English, certainly enough to tell the trail workers what needs to be done. His friend, Frank, smiles lots and we have one conversation. “No English” he tells me. I reply, “No hablas Espanol.” We laugh and keep working.

Then there is Randall. On our first full day at Heliconias Adriel gets a call on his cell phone while we are out working in the rainforest. It seems the old Gringa is needed back at the lodge to help clean. Ok. We were told in our orientation to be flexible, and at least I got out into the woods and carried a couple of loads of dirt.

Randall meets me in the main lodge, hands me a bucket of soapy water and leads me up to the newest, fanciest lodging high on the hill. “Baranda,” he says, slapping the railing on the porch. He makes cleaning motions with the rag. “Escoba.” He holds up a broom and says “ventanas” as he circles his hand over the window. “Oui, je comprends” I say then backtrack and manage a “Si” and a smile.

As I get to work Randall disappears but he checks in periodically to see how I’m doing and direct me to the next cabana that needs cleaning. I write down the words he tells me and mangle them when I try to use them but he corrects me and adds other words to my vocabulary. “Bonito” he says as he looks at the clean windows. Once he runs over and gestures wildly for me to follow him. I do and there’s a sloth hanging from a big tree in front of the lodge. “Pedasoso,” he tells me. “Wow,” I say.

Later Randall shows me the chew marks on the benches and railings (barandas). They’re from the congos, the black howler monkeys. They swoop into the lodge area looking for food and when they can’t find any they jump on the benches, pick them up and slam them down. Randall is great at demonstrating all this, with sound effects.

“By noon I’ve written down two pages of words, the last ones hambre and almuezo – hungry and lunch.” Photo: Helder Rocha

By noon I’ve written down two pages of words, the last ones hambre and almuezo – hungry and lunch. Randall is a great teacher and I feel welcomed to this place.

It’s two days later when I hear about Gizella’s two young children. Randall calls them Chucky Uno y Chucky Dos. This makes my son Jay laugh, even though he had to put up with them out on the trail. Six-year-old Kembri and his five-year-old sister Kembli ran wild in the woods, driving the trail workers crazy. It’s summer vacation, their mom is busy working and there are no other kids around to distract them. But they’re so cute, I tell Jay. He just shakes his head.

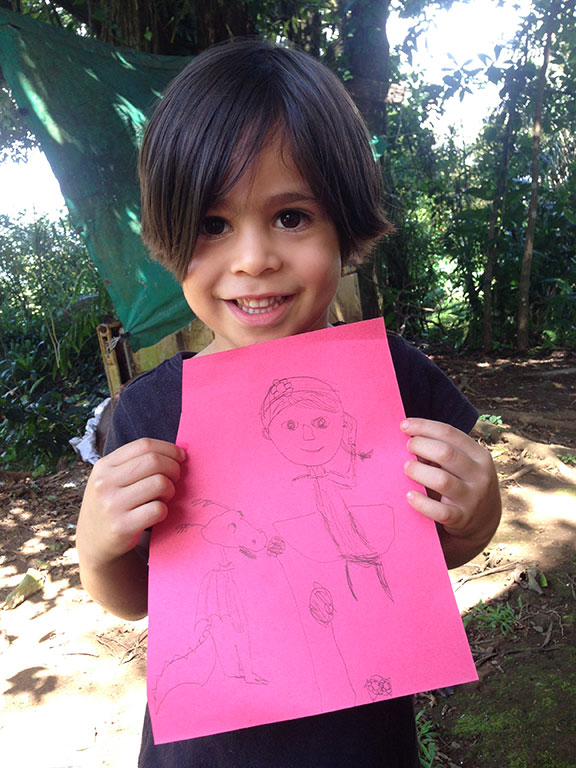

The next morning Kembli arrives with construction paper, colored pencils, scissors and a bottle of glue. I can’t resist sitting with her and drawing animals. I cut them out and she uses massive amounts of glue to glob them on another paper. Kembri joins us and the quiet fun lasts for about ten minutes and ends in a wrestling match. I ask their mother, Gisella, if I can take the kids for a walk on the short trail. Her look says, “You bet. Anything to get them out of my hair.”

And so I become the babysitter. We walk in the rainforest, or rather I walk and the kids run and crash through the vegetation. We pick up sticks and pretend they are machete. We draw pictures. We reach up into the orange tree to dislodge the ripe fruit. “Aqi, Aqi” the kids tell me to stay by the tree and run off to the kitchen. Kembli runs back with a large, sharp knife in her hand. I take it from her and, as instructed, cut the oranges while they sprinkle each piece with salt.

Kembri is annoyed when I don’t understand him. Once, when I am tuning over soil in a vegetable garden he says a word over and over. I ignore him and he disappears, returning at a run with a piece of paper in his hand. Oh, now I get it. He wants me to draw with him again.

Kembli doesn’t seem to mind my muteness, as long as I give her piggyback rides and neigh like a caballo. When she is tired we snuggle together in a hammock or walk down to feed mani (peanuts) to the piglets and hold the new baby chicks. I know both of us value our new, almost wordless friendship. Kembli is the youngest person at Heliconias Lodge and I am the oldest. We understand each other in a deeper way than words.

Is Gringa a racial slur?