Yule Logs, winter heating (and eating)

Party like it’s 599

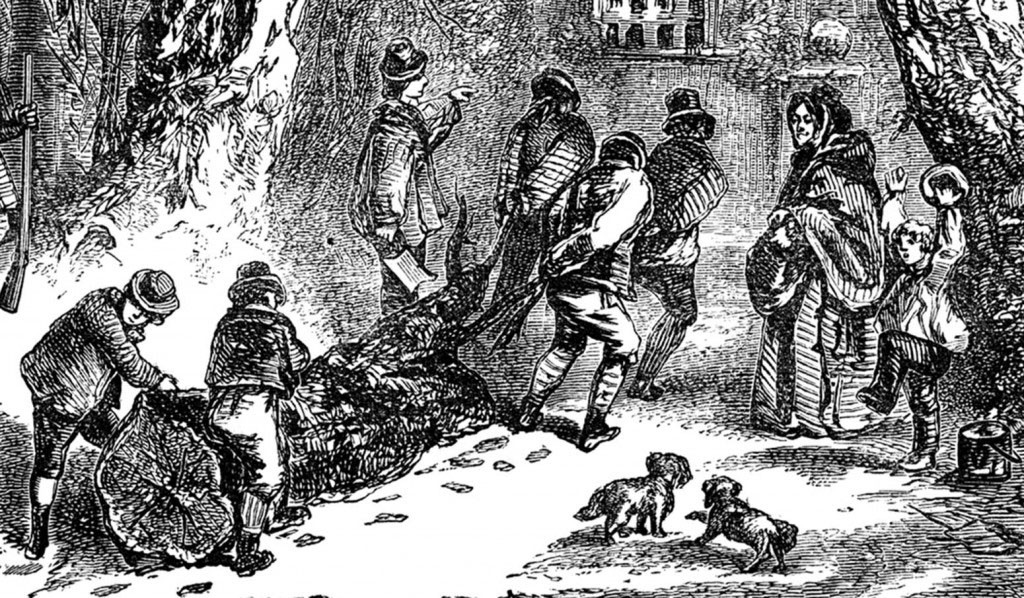

Apparently, the ceremonial burning of a large chunk of wood on or near the winter solstice (Yule to the old Germanic peoples) may have begun as a Nordic custom in the 6th century, possibly earlier. Known as a Yule clog, Yule block, Christmas log and other variants, the Yule log was purported to bring good luck in the new year if it burned all day long without being fully consumed. A remnant was always saved, and used to light the following year’s log. Though the tradition is much less common today, it has not been completely extinguished.

Given the climate there, it is no surprise that the hardy folks in northern Europe thought the best way to observe a winter holiday was to light a tree trunk on fire and gather round it. That’s probably what I would have done, too.

An unburned (an uneaten ) bûche de Noël. Photo: JP, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

The French, on the other hand, put a whole new twist on the thing, inventing a delicious Yule log cake that they never burn, at least not intentionally. It took them a dozen or so centuries to come up with the recipe, but let’s not complain. You don’t have to go to France to taste the bûche de Noël—in Quebec you can find Yule logs that are works of art in addition to being delectable.

Popularly depicted as a birch log, to have a Yule log burn all day and still get leftovers, you might want another kind of wood. While birch is picturesque, it doesn’t compare with many other hardwoods in terms of the heat it gives off and how long it burns. All people are created with equal value, but with logs, not so much.

Your best bet for a long-burning (and heat producing) Yule Log

Sugar maple is the gold standard: 30 million BTUs per cord. Photo: Richard Robles, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Heat value, whether it’s from coal, oil or wood, is measured in BTUs, or British thermal units. One BTU represents the energy required to heat a pound of water one degree Fahrenheit. And even though the U.S. is the only country on the planet not on the metric system, many other nations still use our BTU scale.

Firewood is usually hardwood, though that’s kind of a misnomer. Some “hardwoods” are softer than many types of softwood. Basswood and cottonwood, for example, have a BTU per (dry) cord rating of around 12 million, lower than that of white pine (16 million) or balsam (20 million).

As those who heat with wood know, hard (sugar) maple is the gold standard for firewood, at least in northern New England, releasing a whopping 30 million BTUs per cord. You’d have to burn twice as much butternut or aspen to get the same heat value. Hickory, beech, black locust, white oak and ironwood (hop hornbeam) come in just behind hard maple. The iconic paper birch has about 20 million BTUs per cord, respectable but not a premium fuel. Especially if you are banking a year’s worth of luck on having it last all day.

Of course there are other considerations besides BTU value in choosing firewood. Even though balsam heats better than butternut, it makes more creosote and throws a lot of sparks. Wood moisture content is also critical. When you burn wet wood, much of the wood’s heat value goes into boiling off the water. Fresh-cut elm is 70 percent water by weight; you’d get very little heat from that, assuming you could even keep it lit. Outdoor furnaces, because they have a blower, are capable of burning green wood. This might be seen as a convenience, but if you burn unseasoned wood in an outdoor furnace you’re spending twice as much time, doing twice the work compared to burning dry wood—how’s your back these days, anyway?

A virtually heartwarming Christmas alternative since 1967 is the yearly yule log TV program. Photo: Joseph Malzone, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

A virtually heartwarming Christmas alternative

In the Balkans and parts of southern Europe the Yule log tradition lives on. If you’re one of the few Americans who will be burning an actual Yule log in an open hearth this year, you probably have a good chunk of dry hard maple or hickory set aside, plus a remnant of last year’s log with which to help light it.

But if that’s not your tradition, you can join millions of Americans who tune into the televised Yule Log Program on Christmas, now on the Web of course. That log apparently not only burns all day, but has done so since the program’s inception way back in 1967. I’m sure the Department of Energy is working to find what species of tree it’s from, because with just a few of those trees we could solve a lot of our energy problems.

May your holiday season be healthy and happy, and may your Yule log burn only if that is your plan.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Tags: christmas

I am a Canadian born in Martinique, where we also have a bûche de Noel. Even though the tradition started out burning or baking the yule log, I find it funny that more and more the tradition (in France as well as in les Antilles françaises) has switched to a bûche glacée de Noel (a frozen Christmas log). Joyeux Noel, everyone!

It has been brought to my attention that fir and pine do not cause more creosote buildup than hardwoods, so long as it is burned dry.

Also, BTU tables for firewood, even from reputable sources, vary somewhat in the values they report. Growing conditions, and to some extent genetic variation, will result in different BTU numbers for the same tree species.