Thirsty maples: Will this drought year sap next year’s sap production?

Jackson, age 3, samples maple sap from the tap in Blue Mountain Lake. Archive Photo of the Day March 19, 2010: Jamie Nile Strader

Given that maple producers have to boil down roughly 40 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup, you would think that dry weather might improve things. Obviously if drought could get rid of a bunch of water for free, the sap would become concentrated and you wouldn’t need to boil as much. Heck, in an extremely dry year maybe we could just drill into a maple and have granular sugar come dribbling out.

If only it worked that way. In general, a shortage of water during the growing season hampers the production of sugar and leads to lower sap sugar concentrations the following spring. Green plants have a magic formula for turning sunlight into sugar, and it calls for a few simple ingredients: water, carbon dioxide, sunlight and chlorophyll. If one item is missing, the transformation won’t work. I’m told most spells fail for want of a newt’s eye or some such, but if a thing as basic and usually commonplace as water is in short supply, the miracle of photosynthesis slows to a snail’s pace (which is likely used for some other spell).

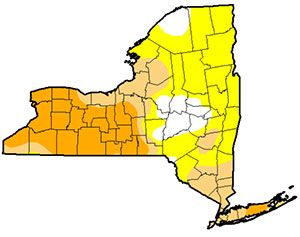

Drought monitor map for New York on July 26, 2016. Yellow is abnormally fry, tan is moderate drought, orange is severe drought. Map: USDA

On paper, 2016 was only slightly below normal in rainfall for the season. The records don’t tell the whole story, though, because we experienced a very bad drought. As dairy herd managers and stand-up comics will tell you, timing is everything. Moisture is more critical during the first half of the growing season as compared to the latter, and most parts of NYS had little or no significant rain between early June and late August.

Not only do June and July have the longest days of the year, the sun’s angle is steepest and its effect most intense at this time. Couple those facts with low humidity, scant cloud cover and frequent and persistent winds, 2016 saw some of driest-ever soils statewide, and some regions broke records for low soil moisture. On rocky upland sites and other locations with thin soils, the situation was even more dire.

Average to above-average rain through September into October finally pulled most of New York from the drought-index rolls by the end of October. That was better than continued drought, but far too late to avoid damage to trees. In certain locales, wooded hillsides were completely brown by early August, and foresters do not know what to expect from these in 2017.

Even trees that showed few overt signs of stress will need more than a good season in 2017 to recover from last summer. Dr. George Hudler, plant pathologist and Cornell professor emeritus, says that trees may need two to three years to recover from a drought. Ironically, those brown lawns which appeared dead were merely dormant, and grew back from their slumbering but undamaged root crowns.

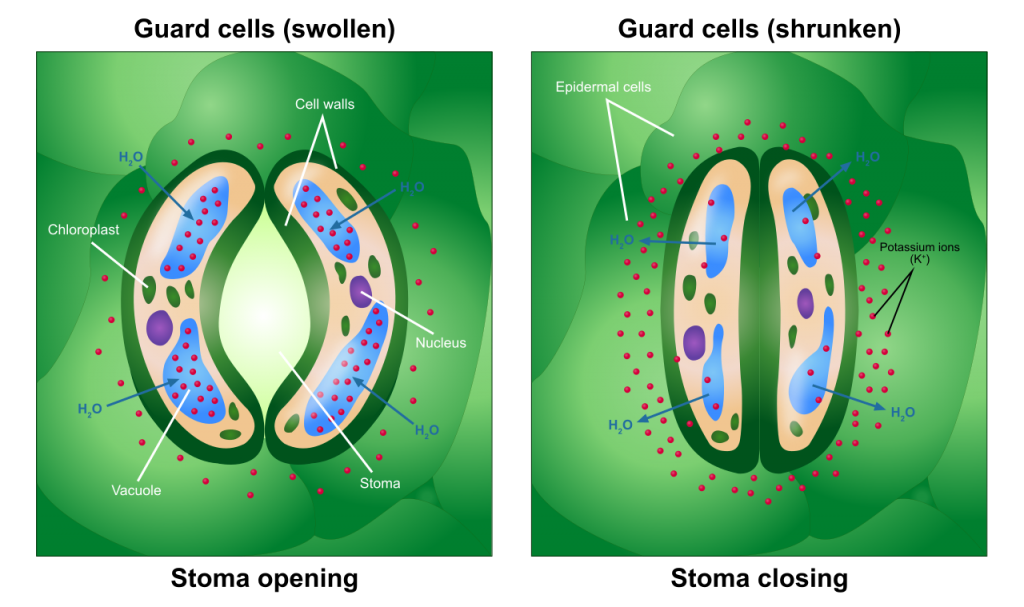

Once leaves adjust for water conservation, it takes a long time to reverse the process. Illustration: Ali Zifan, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Apparently, bad weather will mess with one’s hormones. If one is a tree. Prolonged dry conditions cause a shift in the production of growth-regulating hormones. Among other things, more abscisic acid comes online. This leads to stomatal closing, a plus in terms of moisture retention, but it takes a surprisingly long time to reverse. As its name implies, abscisic acid creates an abscission zone between leaf and twig. Perfect for the fall, but when the plumbing that connects a tree to its leaves starts to get unplugged early, the tree will have a hard time restarting the sugar factory when the rain finally comes.

A reverse-osmosis machine helps maple producers to concentrate sap, but in a drought, reverse osmosis is not their friend. Ron Kujawski of the University of Massachusetts Agricultural Research Station explains it well:

“When a soil water deficit exists, the result may be an increase of solute concentration outside the roots compared to the internal environment of the root. Such a situation leads to reverse osmosis, i.e. a net movement of water from the cell to the soil solution. As this happens, the cell membrane shrinks from the cell wall and may eventually lead to death of the cell.”

98% of tree roots are in the top 18 inches of soil. Illustration: Univ. of Minn. Extension

About 90% of tree roots reside in the top 10 inches of soil, and 98% in the top 18 inches. As dry soil pulls away from roots, the root hairs, and then the fine absorbing roots near the surface, desiccate and die. Eventually, slightly larger secondary roots also die. Among other things, this means that trees have to use energy stores to replace these before they can absorb any moisture once the dry period ends.

Also, each place where a root hair or root has died is a wound into which disease can enter. For a tree, this is a bad time to have pathogens knocking at its door, because it needs water to make defensive chemicals. Again, Ron Kujawski: “Among the types of diseases likely to occur in response to drought stress are root rots, cankers, wood rots, and wilt… Nectria canker and Cytospora canker are almost always associated with drought stress… it is the inability of the plant to synthesize protective chemicals and compartmentalize wounds that allows for disease infection and development. Drought-stressed trees are also predisposed to other diseases including Diplodia tip blight, Rhizosphaera needlecast and Verticillium.” Trees will also be more vulnerable to insect attacks, especially borers, in the years following a severe drought.

Although no one knows for sure what this maple season will bring—and as always, much depends on the weather—Cornell’s Extension Forester Peter Smallidge shared a few preliminary thoughts with me:

Low sap sugar content favors producers using a reverse osmosis system. Photo: Vermont Maple Sugarmaker’s Association

“There may have been some maple stands that suffered less than the average. I wouldn’t be surprised if maple sap sugar was lower in 2017 than in previous years, but unless a producer has some reason to believe there was particularly acute drought stress on their trees I don’t see a need to reduce tapping. My anticipation of lower sap sugar will favor those producers who have reverse osmosis. If sugar concentration is low, the producer without RO will spend more on fuel to produce the same amount of syrup.”

Maple producers on drought-prone sites who are concerned about their sugar bush may want to get in touch with a Cornell Master Forest Owner Volunteer, or call their local Cornell Cooperative Extension office. They can also contact authorities such as Drs. Smallidge, or Michael Farrell of the Cornell Maple Research Station. Time will tell how our maples and other trees fare, and even the experts will be learning more this year and next about the effects of drought.

Residents of the North Country can find out a lot more regarding maple health as well as maple production, marketing and more at the St. Lawrence County Maple Expo on Saturday, January 28 from 8AM to 3PM. The Expo will be held at the Gouverneur High School on Barney St. in Gouverneur, and includes lunch. For more information call (315) 379-9192 or visit stlawrence.cce.cornell.edu

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Tags: drought, forestry, Maple syrup, nature