Pollen Nation

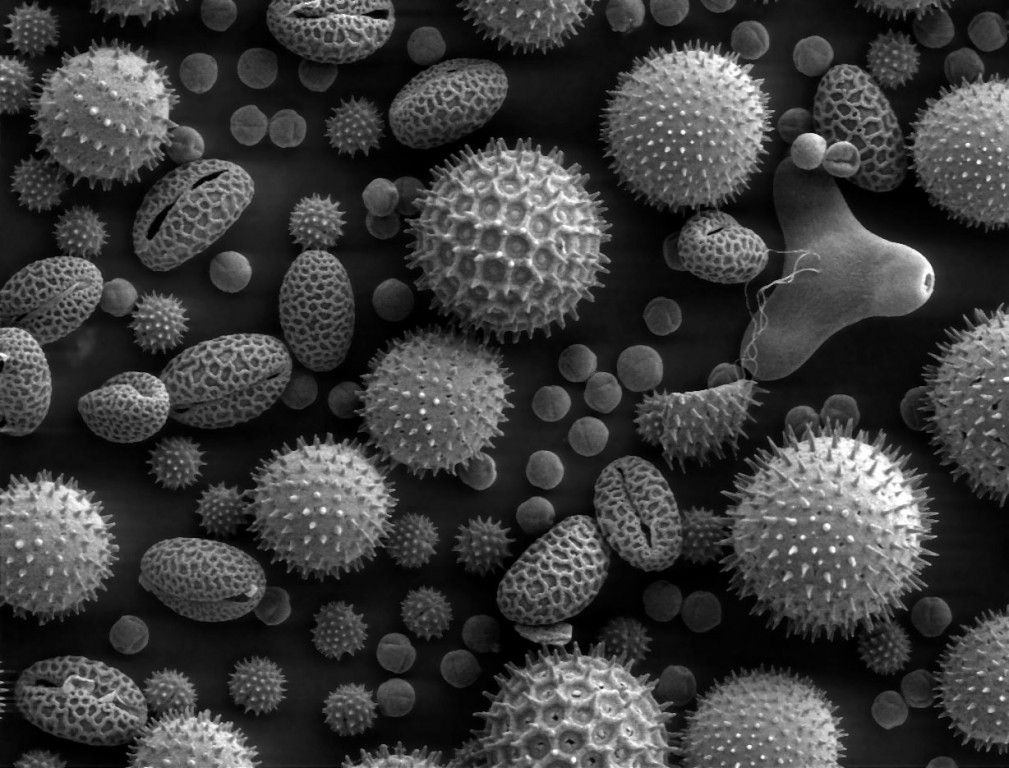

Pollen from a variety of common plants magnified 500 times. Photo: , Dartmouth College Electron Microscope Facility, public domain

There’s pollination, and then there’s Pollen Nation. The first is necessary to produce food, and for the continuation of forests, prairies and other terrestrial ecosystems. The second is what we are this year, beset with more than our usual share of pollen, which has filled sidewalk cracks and coated windshields this spring.

Anything outside winter can be pollen season. Various tree species like willow (a common allergen) and soft maple typically begin to shed pollen before all the snow has melted, and depending on conditions, forage grasses may continue to flower in very late fall. Not everyone is sensitive to the same type of pollen, and of course there are other allergens floating about such as mold spores, but certain types of plants—ragweed comes to mind—seem to trigger symptoms in a high percentage of allergy sufferers.

Pollen of course is the male contribution to a plant seed, many of which come wrapped in tasty coverings as is the case with tomatoes, cukes, apples, melons and the like. Most plant species have male and female reproductive parts conveniently located on the same plant. These are called monoecious. Sometimes everything is in the same flower, like apples, and others have separate male and female flowers, like squash. A few species are dioecious, meaning they have separate male and female plants. Holly and ginkgo are two examples.

Like every other living thing, plants have an innate drive to have babies and carry on the species. To accomplish this, plants have to figure out how to get pollen grains to make friends with their ovaries. Generally plants use one of two strategies.

An Andrena sp. bee with a full load of pollen on a Calendula flower. Photo: Alvesgaspar, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

One is to bribe insects or other critters to carry pollen from the male flower part to the female. These plants make flowers that are recognizable as such: colorful, fragrant, affairs with sweet nectar deep within each flower, as payment for pollen delivery. These plants make heavy pollen. Well that’s relative, because bees have to be able to pick it up, but the pollen is too heavy to waft around on the breeze. There is an easy test to tell if a flower causes allergies or not. If you can see it, it is not to blame for your symptoms.

On the other hand, making showy, sugar-filled flowers is expensive. It takes a lot of energy. At some point a group of plants decided it was hard work to attract pollinators, but easy to attract the wind, which could deliver their pollen. They have to crank out loads of the stuff (pollen, not wind), but each grain is miniscule. It is so light that ragweed pollen has been collected 400 miles out to sea. Members of the wind-pollinator club have inconspicuous flowers which tend to be drab and green, and just large enough to get the job done; no bigger. Elm trees, ragweed and grasses belong to this group. So do pines, whose teeny male cones are responsible for the greenish residue all over the place. Luckily, not many people are allergic to pine pollen.

We get a break from all that just after a rain, which washes dust and pollen from the air. A spell of dry weather makes allergies worse, as new pollen keeps getting added to that which is hanging around. Because our seasons get a little longer every year, allergy season gets a little worse over time.

Try a wide brim hat and close-fitting sunglasses to keep your personal pollen load down. Photo: https://www.maxpixel.net/Sun-Protection-Sun-Hat-Sunglasses-Hat-Straw-Hat-2632259:>Max Pixel, public domain

Not that you can do a whole lot about it, but you can look up pollen conditions on any number of websites. Some are hosted by makers of allergy medication, and others by universities and government agencies. Pollen reports give not only the severity, but also tell you what kind is most prevalent at the moment. The U.S. Environmental protection Agency reports air quality across the country (airnow.gov), and the American Academy of Asthma, Allergies and Immunology (aaaai.org) has a good pollen calculator, and there are air quality maps at pollen.com.

People who suffer with allergies can get a tiny bit of relief by wearing a broad-brimmed hat to keep your hair from becoming a pollen collector. Sporting close-fitting sunglasses can help keep some of the pollen out of the eyeballs. And even though line-dried clothes smell the best, don’t hang your laundry on high-pollen days because you’ll be wearing your misery.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.