Got Gas? Burn the “belches,” spare the planet

Cows, lots of milk, lots of methane. Photo: Jean Beaufort, public domain

Even if its precise definition isn’t at the tip of your tongue, most everyone gets the general drift of what is meant by the term biogas – there’s biology involved, and the result is gas. One might guess it’s the funk in the air aboard the bus carrying the sauerkraut-eating team home after a weekend competition. Others would say biogas is cow belches, or the rotten-egg stink-bubbles that swarm to the surface when your foot sinks into swamp ooze.

Those are all examples of biogas, which is composed primarily of methane, CH4, at concentrations ranging from 50% to 60%. Methane is highly combustible, and can be used in place of natural gas for heat or to run internal-combustion engines for the generation of electricity and other applications. Formed by microbes under anaerobic conditions, it is a greenhouse gas twenty-eight times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping heat in Earth’s atmosphere. The fact that it can be useful if harnessed but dangerous if released is why we need to trap biogas given off by landfills, manure pits, and someday, maybe even cow burps.

By itself, methane is colorless and odorless, but it often hangs out with unsavory friends like hydrogen sulfide, H2S, which is responsible for the rotten-egg smell we associate with farts and swamp gas. Not all biogas is equal—the stuff given off by landfills is contaminated with siloxane from lubricants and detergents, and manure-sourced biogas may contain nitrous oxide, N2O. Siloxane, nitrous oxide, and hydrogen sulfide gases are toxic at high concentrations, and are very corrosive. They usually burn off harmlessly when used for heat, but must be removed if biogas is to be used to fuel an engine.

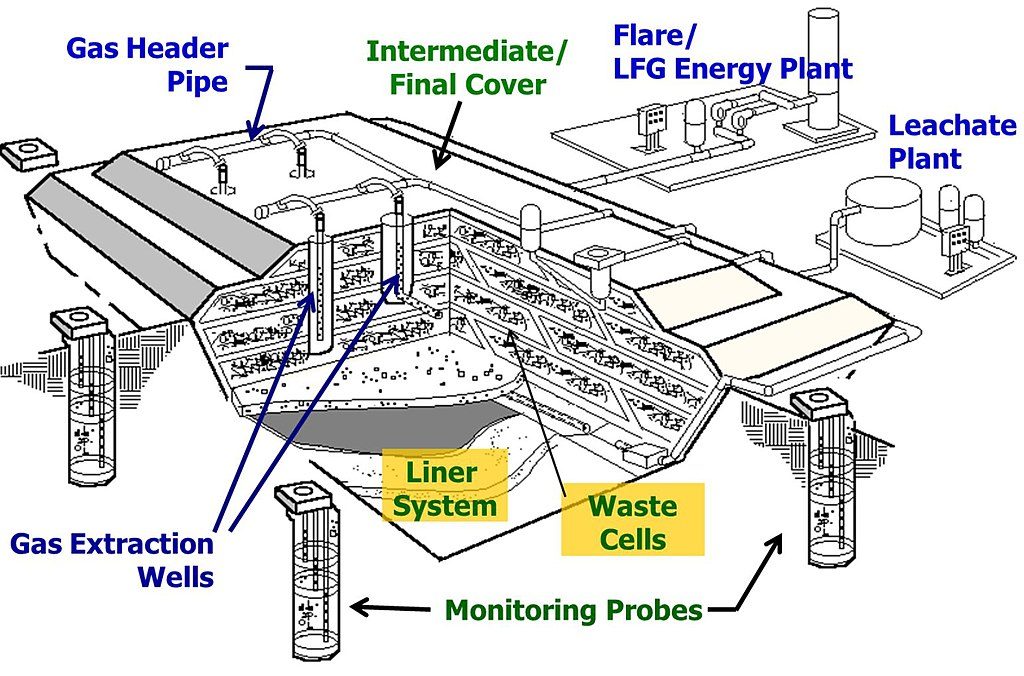

Landfill gas collection system. Diagram: U.S. EPA

As mentioned, methane occurs when organic matter decomposes in oxygen-deprived conditions under the ground. This led to numerous biogas explosions in landfills across the U.S. and Europe, mostly in the 1960s and 1970s, although a series of such incidents in England in the 1980s spurred tighter regulations in that country on collecting biogas. The frequency of explosions at dumps is much reduced in recent times, but it does still happen. A dump at Walt Disney World in Orlando caught fire in 1998. In 2006, the US Army (which is exempt from many environmental laws) evacuated twelve households near one of its old landfills at Fort Meade, Maryland due to high methane levels.

Even though it provides benefits like electricity generation, extracting landfill biogas is necessary for health and safety. But biogas is also produced intentionally in something called a methane digester, which I thought was another word for a cow. Despite the name, these things do not digest methane. Rather they use animal manure, municipal sewage, household garbage, and other organic matter to capture methane, much of which would otherwise have been released to the atmosphere.

Large-scale methane digester beside a manure lagoon in Spain. Photo: Som Energia Cooperativa, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

The basic process is this: an airtight reactor is filled with animal manure or whatever your favorite filling is, and after a 4-part bacterial process and some amount of time you end up with a “digested” slurry that can be used for fertilizer, and biogas. Digester technology can work from a massive industrial scale to a very small backyard unit which runs on household waste.

At about 60% methane, digester biogas is a better fuel than landfill biogas, which tends to be about 50% CH4. Gas from a digester can be used directly for cooking or heating, but must be processed before it can be put to other uses. In addition to being used to run internal-combustion engines, “scrubbed” biogas, which is nearly pure methane, can be injected into the natural-gas grid, or compressed and sold to distant markets.

These days, livestock farmers are being encouraged to install methane digesters as an additional source of income or to offset heating costs. Digesters reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, and manure processed in a digester retains more nitrogen than manure stored in open-air lagoons. It’s not brain surgery, but there is a learning curve, as well as labor inputs. The idea is being promoted now, but it is far from new.

Regionally, operators of the Village of Lake Placid sewage treatment plant have captured biogas and used it to help heat the plant since the early 1980s. The project was begun by Paul Gutman, a former operator. While not universally supported at first, Gutman’s methane-capture program has saved the Village a huge chunk of change over the years.

Small-scale methane digester at a community garden in the UK. Photo: David Hawgood, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

The Chinese have been involved with methane digestion since about 1960, and in the 1970s disseminated something like six million home digesters to farmers. Currently, home digesters are common in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and parts of Africa. On the larger scale, Germany is Europe’s foremost biogas producer, with around 6,000 biogas electric generating plants. Germany also has incentives and subsidies for farmers and others to adopt digester technology.

We may have backyard methane digesters, but to my knowledge there are none for strictly personal use. If you’ve eaten too much sauerkraut you’ll just have to let digestion run its course. Away from others, please.

Clarkson University’s Biomass Group, headed by Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Dr. Stefan Grimberg, has information on its biogas projects, plus links to other resources, on its website.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Tags: biogas, environment, green energy, methane digesters