Not all minds that wander are lost

Bill Watterson, creator of the wildly successful Calvin and Hobbes comic strip, pretty well defined the term daydream with Calvin’s moronic, blissful smile and vacant stare as he battled aliens and dinosaurs rather than paying attention in his first-grade classroom. That more or less sums up my grade-school experience, too.

Although daydreaming has long been maligned as a threat to our Puritanical work ethic, as well as a sign of laziness or insolence, many scientists now believe that it is crucial to innovation and problem-solving. Research strongly suggests that in many cases—air-traffic control would be an exception—it should be encouraged in the workplace and academia. It also likely served an important role in human evolution. And, there is evidence that certain animals may daydream.

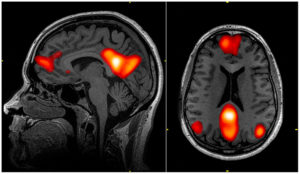

In Michael Harris’ excellent article on the topic in the June 12, 2017 issue of Discover, he cites recent neurological research that puts mind-wandering in a positive context. He highlights the work of Dr. Kalina Christoff, Professor of Cognitive Science at the University of British Columbia, who runs a lab which studies human brain function. Among the ways Christoff does so is through functional magnetic resonance imagery, or fMRI, as well as through controlled behavioral studies on student volunteers.

Magnetic resonance imaging of areas of the brain in the default mode network, thought to be the brain regions active when daydreaming. Image: John Garner, public domain

Christoff’s fMRI studies show that “…our brains are very active when we daydream – much more active than when we focus on routine tasks.” She says that while analytical thinking and focused attention are necessary, our brains need time to organize information to solve a problem or answer a question. Writing for Live Science in September 2016, Agata Blaszczak-Boxe states “…recent research has also shown that daydreaming, much like nighttime dreaming, is a time when the brain consolidates learning. Daydreaming may also help people to sort through problems and achieve success.”

In one of Dr. Christoff’s experiments, volunteers were allowed to work on a complex problem for a few minutes. Then for 15 minutes, half the subjects were given manual tasks which required focus, and half were allowed quiet time. The half which was allowed idle time was 40% more efficient at solving the task they were presented earlier.

“Imagination is more important than science.” Albert Einstein in 1935 at Princeton. Photo: Sophie Delar, public domain

Einstein was a strong proponent of daydreams, and famously said “Imagination is more important than science.” Dr. Felicity Mellor, who teaches Science Communication at Imperial College in London, is cited in the same article as being highly critical of the emphasis on collaboration and team atmospheres in business and education if it comes at the expense of time to work alone.

In Michael Harris’ piece, Dr. Christoff explains that the wandering mind does not filter any thoughts. It can thus make connections it would not normally make. She says “Analytical thinking is ideal for weighing options in a well-defined problem, [but it] is antithetical to inspiration.” We need idle time to problem-solve.

My friend Dr. Curt Stager of Paul Smith’s College in northern New York State once told me that some scientists believe autism-spectrum conditions like Asperger Syndrome were important for our survival as a species. The hypothesis is that having a small percentage in the population who think “outside the box” and are not apt to go along with popular sentiment would have possibly been spared from a disaster which befell the majority. By the same token, daydreaming is likely to have been key to hominid survival and the development of Homo sapien as a species.

Again in the Harris article, Alison Gopnik, Professor of Psychology at UCal-Berkeley lends credence to this idea. Quoting Harris, “[Gopnik] argues the rush of pleasure we get from an ‘aha moment’ may be built into our DNA to ensure that we learn more about the world…If we evolved to take pleasure from the moment fresh connections are forged, then letting our mind wander is no longer a guilty indulgence — it is crucial to our success and survival.”

Baby gorilla daydreaming. Photo: Eric Kilby, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Research on daydreaming in other animals is scant, but there seems to be some early indications that other primates, as well as some birds, might daydream. We know that ravens understand the concept of planning for future events, for example. In a 2010 article in the journal Behavioural Brain Research titled “Behavioural Evidence for Mental Time Travel in Nonhuman Animals,” T. Suddendorf and M.C. Corballis summarize a literature review on the subject. While they admit that direct evidence of animal daydreams is equivocal, there is indirect evidence, and more research is needed.

Obviously there is a downside to daydreaming, which can catch us unawares at inappropriate times—meetings, conversations with a significant other. You don’t want your surgeon’s mind wandering off during an operation. But Katie Heaney, writing for TheCut.com in June 2018, outlines what is called “maladaptive daydreaming,” or MD. This is not an official medical diagnosis, but it seems to plague a small number of people, in some cases causing them to lose jobs and relationships.

Ms. Heaney cites research done by Drs. Nirit Soffer-Dudek and Eli Somer, who think MD may be related to serotonin imbalances, and possibly childhood trauma. To quote Heaney, “Many MD sufferers describe their extended daydream as compulsory, or outside their control — on average, the subjects of the aforementioned study reported spending four hours a day daydreaming.”

Calvin may or may not have had a serotonin problem, but I suspect Bill Watterson patterned the frenetic boy after his childhood self. I loved that series, and am glad no one ever “cured” Mr. Watterson’s imagination as a boy.

Tags: daydreaming, neuroscience

.jpg)