A windshield survey of back-country bugs

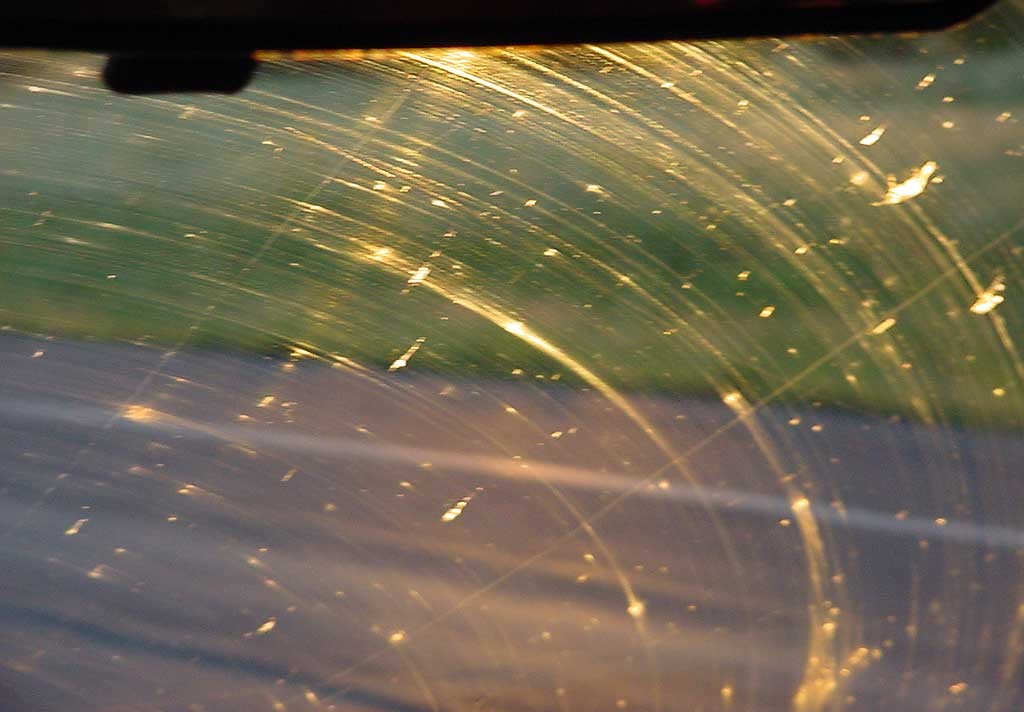

Sometimes you’re the bug, sometimes the windshield. Photo: Jason Eppink, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Next time you arrive at your cottage, camp, or favorite fishing spot and the car’s grille is bristling with wings and other insect body parts, its windshield greased with bug guts, you should be happy. Those insects develop underwater and their presence is an indication the water quality thereabouts is very good. And that you should bring paper towels and glass cleaner next time.

Flying fish excepted, it seems odd to call an airborne creature aquatic. But these insects spend most of their lives in an aquatic life stage called a naiad or nymph. They breathe through gills that, although well-developed, are readily damaged by sediment and other kinds of water pollution.

Nymphs look nothing like the adults who spawned them. They’re squat mini-monsters with faces even their mother couldn’t love. Depending on species and environmental conditions, they remain submerged for as many as five years.

When it’s good and ready, a nymph will haul itself up on shore, anchor its claws into a log or something and unzip its Gorgon costume. Then, an elegant winged creature steps out of the empty monster-husk, spreads its wings and takes to the air. After that impressive magic trick I imagine these bugs are disappointed to learn they may have only a few hours to find a mate before they die.

The longevity-challenged mayfly. Photo: Bjorn S., Creative Commons, some rights reserved

The insect with the shortest adult life is the mayfly, sometimes known as shadfly. These are the guys that hatch, or more accurately emerge, in such great numbers that your windshield can become an opaque gut-smear in seconds when you pass through a cloud of them. (God forbid you’re on a motorcycle.) Mayflies can be so numerous along the Great Lakes that they show up on Doppler radar. True story.

Mayflies belong to the order ephemeroptera, referring to their brief lives on the wing. Almost all species require running water with high dissolved oxygen and low turbidity, the same conditions trout need. They’re the sheep of the aquatic world, grazing on algae and casting nervously over their shoulders for carnivores like dragonfly nymphs. If they make it to adulthood they emerge to find themselves without a digestive tract with somewhere between five minutes (no kidding) and a few days to live. Some reward.

Dragonflies are more likely to bounce off a windshield than splat across it, but an unfortunate number end up wedged in car grilles. Ecologists talk about the “edge effect,” because the edge of a clearing is an especially productive habitat and perfect hunting grounds for dragonflies. Perfect hunting except that many roads are long narrow woodland clearings through which speeding steel-and-glass boxes hurtle.

Like their adult form, dragonfly nymphs are efficient predators. Their fearsome hunting gear includes hinged “lips” with sharp grapples on the end, which they deploy with speed and precision. Tadpoles, minnows, other aquatic insects, and on occasion even fellow dragonflies are all fair game. While their pollution sensitivity varies by species, in general dragonfly nymphs are not as fussy as mayflies about water quality, and you can find them in shallow beaver ponds as well as pristine brooks.

Whereas mayfly species are nearly all early-season phenomena, dragonflies emerge throughout the season, often with a noticeable wave early and another pulse quite late in the summer. Adults live to a ripe old age; some make it past their one-month birthday. They eat biting insects and dress in bright colors, which may be why dragonflies figure into popular culture more than other insects.

Stonefly on the windshield? You’re near clean water. Photo: Lindsay, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

If you find a stonefly in your automotive bug collection, you’re in the neighborhood of some of the cleanest waterways one can find. Stoneflies are not as numerous as mayflies or as noticeable as dragonflies so they are easy to overlook. Similar in size to a mayfly, they are flatter and have long, slender antennae. They hold their membranous wings directly over their bodies, which gives them a very narrow profile at rest.

Stoneflies are not rare, but their nymphs only survive in the clearest and most highly oxygenated water. Equal-opportunity diners, they munch on algae and other insects alike. Turn over a rock in your favorite back-country stream and you’re likely to find one clinging to the underside.

Blackflies and deer flies are also aquatic insects, but their habits make them less prone to becoming hood ornaments. Mayflies, which are not even capable of biting, get plastered across cars and trucks but we seldom bag a single blackfly. Life is so unfair. That’s it, I’m taking the day off to go fishing.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Keep writing these fine articles! They are a treat to read.