Apply “uncommon sense” along with pest control products

There’s an old saw that the trouble with common sense is that it is rare. I see the point, but it doesn’t account for the fact not everything makes sense. Sure, we know that a relatively safe drug like aspirin is available over the counter, while opioid painkillers must be prescribed by a licensed medical doctor due to the potential for overdose or addiction. And because of the increased risk, driving a gasoline tanker requires more training than operating a car. Things like that make sense.

When it comes to pest control, we naturally assume that the same logic applies. Common sense would suggest the stuff your kid can buy at the garden center is safer than products restricted to trained, licensed pesticide applicators. However, this is not necessarily true.

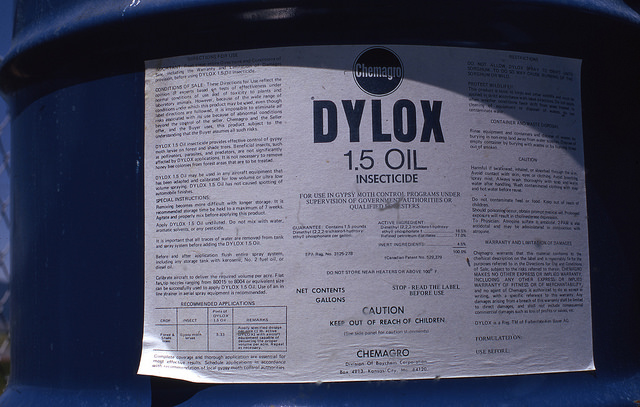

Dylox, a brand name of trichlorfon, may control lawn grubs, but it is also easily absorbed through the skin and can cause permanent nervous system damage. It is banned in many countries, but not the U.S., except for food crops. Photo: USDA Forest Service

Many restricted products are dangerous, no question. But in a lot of cases, they are “behind the counter” because it takes a good deal of training and skill to use them. Restricted products may need to be mixed at varying concentrations depending on the target pest and situation. They may need to be combined with other products, or diluted with water of a very specific pH range. So the fact you need a license to buy a certain pesticide is not a reliable indication of its toxicity.

Consider a common pesticide used around the home. Trichlorfon, also known as Metrifonate or Dylox, is mainly employed to control lawn grubs. According to a 2016 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report, “Average domestic usage of trichlorfon is about one million pounds of active ingredient [equivalent to 2.1 million pounds of product] per year. Total usage is allocated mainly to lawn care (74%) and golf courses (18%).”

When pesticides are approved by the EPA, the agency does not certify that those products are safe, but rather that when a pesticide is used according to the label, the aggregate risk to human health and the environment “…does not exceed Agency concern.” In cases where a product has been deemed hazardous even when used as directed, it takes many years to get it pulled off the U.S. market.

According to EXTOXNET, a collaborative pesticide information project of Cornell University, Oregon State University, the University of Idaho, U. Cal-Davis, and Michigan State University, with support from the USDA National Agricultural Pesticide Impact Assessment Program, “Trichlorfon is an irreversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. It decreases activity of the cholinesterase enzyme which is necessary for normal nervous system function. As with all organophosphates, trichlorfon is readily absorbed through the skin.”

EXTOXNET files also state that even minor trichlorfon exposure can cause “…impaired memory and concentration, disorientation, severe depressions, irritability, confusion, headache, speech difficulties, delayed reaction times, nightmares, sleepwalking, and drowsiness or insomnia. An influenza-like condition with headache, nausea, weakness, loss of appetite, and malaise has also been reported.” These symptoms may show up several weeks after exposure, and persist for weeks, months, or more than a year.

When chemicals are evaluated for toxicity, one of the most common parameters is called the “oral LD50,” meaning the concentration in mg/kg or ml/kg (parts per million) of the substance which kills 50% of test animals, often mice or rats, after ingestion. The oral LD50 of trichlorfon in rats is around 500 mg/kg. For table salt it is 3000 mg/kg, and for water the oral LD50 is 94 ml/kg. This sounds like trichlorfon is safer than water. Actually, to make that argument would be to utterly embarrass oneself. When it comes to exposure to a neurotoxin where even an infinitesimal dose may have a significant effect in some individuals, it is the height of absurdity to consider LD50 as a measure of toxicity.

Trichlorfon has been banned in the EU, Brazil, Argentina, New Zealand, and India has agreed to a complete ban in 2020. In the US, it is now restricted to nonfood applications. Not to pick on this product in particular, but that spray can, or bag of pellets or dust at the garden center is not necessarily benign just because a small child can walk in and buy it.

One of the most important considerations in pest control is to properly ID the target. Ants and bees are attracted to tree wounds made by sapsuckers, and may be blamed for the damage because they “look guilty.” A spider mite infestation may not be affected by an insecticide, because they are not insects.

An understanding of both host and pest biology is also important. As an example, Japanese beetle damage to fruit trees in September has no impact on tree health, and should not be treated. For more information on pest management, go to nysipm.cornell.edu, or call your local Cornell Cooperative Extension office.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Tags: environment, health, pest control