Who knew? Japanese influence in Inuit print art

“Owl, Fox and Hare Legend,” 1959. Artist:Osuitok Ipeelee

Printed by the artist, with James Houston, Stencil. Photo: Marie-Louise Deruaz (Image courtesy of Carleton University Art Gallery)

Peter Simpson’s Big Beat arts blog in the Ottawa Citizen often brings things to my attention worth sharing with NCPR’s audience. One of his recent finds is a specific exhibition happening at the Carleton University Art Gallery: Inuit Prints: Japanese Inspiration 29 September – 14 Dec.

From the event’s website:

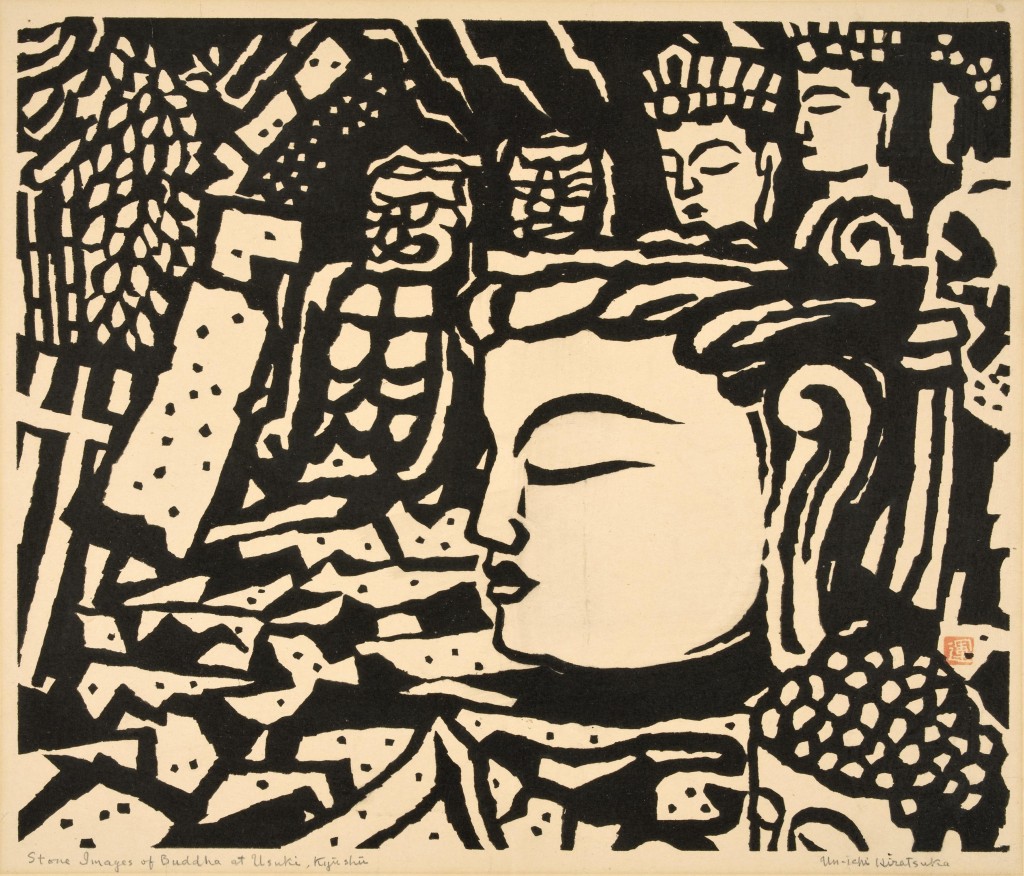

Kinngait Studios, in Cape Dorset, Nunavut, is the oldest and most successful printmaking enterprise in Canadian history. In the late 1950s, James Houston studied in Japan with the master woodcut printmaker Un’ichi Hiratsuka, bringing his newfound knowledge of Japanese techniques and materials back to Cape Dorset. Inuit Prints: Japanese Inspiration tells the story of that momentous cross-cultural encounter and explores its extraordinary results. It features rare, early prints by such artists as Lukta Qiatsuq, Tudlik Akesuk, and Osuitok Ipeelee, juxtaposed with the prints by Japanese artists that Houston brought to the Arctic in 1959. The exhibition reveals the many ways in which the now-famous artists of Cape Dorset creatively “localized” Japanese influences.

You can see more about Kinngait Studios at their social media page.

Simpson reminds the reader that the 2012 exhibition of Vincent Van Gogh at the National Gallery in Ottawa included Japanese prints and that Van Gogh was deeply influenced by that style of art. Indeed, according to this excerpt from a letter Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, Japanese prints imbued his artist’s eye with a whole philosophy of life:

“When we study Japanese art, we see a man who is no doubt wise, philosophical and intelligent. And how does he spends his time? Studying the distance between the earth and the moon? No. Studying the political theories of Bismarck? No. He studies a single blade of grass. But this blade of grass leads him the draw plants of all kinds, then the seasons, the overall aspects of the landscape, then animals, and finally, the human figure. This is how he spends his life, and life is too short to do the whole. Come now, isn’t it almost a true religion which these simple Japanese teach us, who live in nature as though they themselves were flowers? And it seems to me that we cannot study Japanese art without becoming much gayer and happier, and we must return to nature despite our education and our work in a world of conventions.”

Put that way, man-as-a-small-part-of-the-natural-whole also sounds very applicable to Inuit culture.

Simpson’s review adds this:

Exhibitions of Inuit art are now common down here in the southern parts of Canada, and justifiably so. Yet this challenges curators to find unfamiliar but meaningful ways to present the art. To see the work of Japanese and Inuit artists side by side is to see the art of Cape Dorset in a way that, for most non-experts, is fresh, and most welcome.

Really, it can sometimes be a surprisingly small and interconnected world.

“Stone Image of Buddha at Usuki,” ca. 1940 Artist: Un’ichi Hiratsuka

Printed by the artist, woodcut. Gift of Alice W. Houston

Photo: Marie-Louise Deruaz (Image courtesy of CUAG)

Tags: art, canada, Inuit prints, Japanese prints, Van Gogh

.png)