Canadian broadcast content rules up for review

Beacon of CanCon: The tower atop Clifford Slope at the Camp Fortune ski area in Gatineau Park is the transmitter site for all of Ottawa’s television and most FM radio stations. Photo by James Morgan

Change could be in the air when it comes to what’s on the air in Canada. Melanie Joly, the Minister of Canadian Heritage, who is responsible for cultural programs, recently announced a review of the regulations requiring a certain amount of Canadian content, better known as CanCon. The reason for the review is to determine the place of Canadian content in a media industry where digital content increasingly dominates. The last time CanCon rules under the Broadcasting Act were reviewed, it was 1989 and digital media did not exist like it does today.

CanCon first arrived under the Broadcasting Act of 1968. For radio content, the MAPL formula was introduced in 1971. This very Canadian acronym is used to identify if a song is considered Canadian content according to Music, Artist, Performance, and Lyrics. One or more of these items is indicated on an album cover, or these days—probably a computer screen to tell radio programmers and announcers if a song qualifies for meeting the hourly CanCon requirements. Right now, those requirements are generally that 35 percent of the music played every hour on most English language commercial stations has to be Canadian according to the MAPL standards. On CBC Radio, it’s 50 percent. Until 2015, the requirement for commercial television stations was 55 percent, but it was scrapped entirely. Those stations still have to air Canadian programs, but the idea behind scrapping the minimum was to encourage more good quality Canadian programs instead of several poor quality ones. Specialty stations still have to air 35 percent Canadian programming and CBC Television airs almost all Canadian programming, aside from the very popular British series Coronation Street. CanCon regulations are enforced by the Canadian Radio-Television and Communications Commission (CRTC)—Canada’s equal to the FCC in the US.

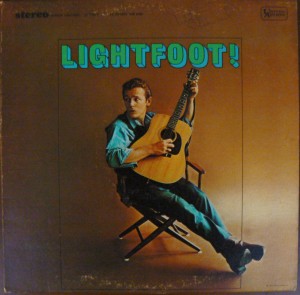

Gordon Lightfoot’s first LP, 1965. At the time, he and Bob Dylan had the same manager, Albert Grossman. Photo by James Morgan. Album from the author’s collection.

Broadcasters had a mixed reaction to CanCon requirements when they were new in the early 1970s. Len Arminio arrived at CHEX-TV and radio in Peterborough, Ontario in 1972 from Massachusetts. His career began in the late 1960s at WBUR in Boston, which became one of NPR’s charter member stations when the network began in 1971. Arminio, who covered city hall and the police beat, and later served as news director says CanCon had no direct impact on news programming, but notes radio audience numbers always spiked at the top of the hour when newscasts generally aired. That means a Canadian record would be exposed to a bigger audience if it was played close to the top of the hour. Arminio said programming staff and station management often found the need to ensure CanCon requirements were being met as “onerous.”

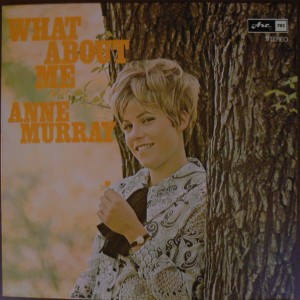

Anne Murray’s first LP was only released in Canada in 1968. Photo by James Morgan. Album from author’s collection.

CanCon rules gave even more airplay at home to performers whose careers had already taken off in the 1950s and 1960s including artists like Paul Anka, Bobby Curtola, Gordon Lightfoot, and Anne Murray. CanCon requirements helped enable the careers of many other artists to get better recognition at home and not have to rely on instantly making it big in Los Angeles or Nashville. This includes acts like Rush, Bryan Adams, Celine Dion, Alanis Morissette, and Shania Twain. CanCon also led to a number of new TV series. Some were fairly high quality variety, drama, and comedy shows. Other CanCon programs were low on budget and talent, and quite clearly only developed to meet requirements. The Trouble with Tracy and Police Surgeon were 1970s CTV network productions that fell into that category. CanCon is what led to Canadian programs like The Red Green Show (PBS) and Due South (CBS) eventually finding popularity in the United States. What also helped was that American networks took notice when they found out Americans living near the border were watching and enjoying Canadian shows on TV. Many North Country residents grew up watching, and still do watch CJOH (CTV) or CBC from Ottawa and CKWS, Kingston. The same goes for radio stations in Kingston, Brockville, Cornwall, and Ottawa that have strong North Country audiences.

The CKWS-TV and radio building in downtown Kingston. The stations are all owned by Toronto-based Corus Entertainment. Photo by James Morgan

The recording and broadcasting scene is very different now. Music is downloaded more often than it is purchased off a store shelf. Listeners are often tuning into highly specialized satellite radio or online streaming services to listen only to the music they like. Television series produced exclusively for digital services like Netflix are often more popular than what networks are offering. With so many ways of selling, listening, and watching to broadcast content these days, the question is raised: are CanCon rules still needed? They helped create a strong pool of and market for Canadian talent in the mainstream, but now that the market is well established, are rules still needed to enable it or instead protect it?