Deer in the wild “Live fast, die young”

Just about everyone who saw the Walt Disney classic “Bambi” shed a tear, or at least stifled the urge to lacrimate (that’s cry in Scrabble-ese). Even if I had known of the devastating effects deer have on forest regeneration, not to mention crops, landscapes, and gardens, it still would have been a trauma for my five-year old self when Bambi’s mother got killed. (Oops—spoiler alert there, sorry.) But how might the movie have ended if they had all lived happily ever after?

This four year old buck at a wildlife research station has already lived twice as long as the average white-tailed deer in the wild. Photo: Penn State, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

What is life like for those few lucky, possibly smarter, white-tailed deer which manage to avoid cars, coyotes, projectiles, and parasites beyond the first few years of existence? Could an aged deer manage to gum your hostas to a nub when its teeth have worn away? I picture a wizened Grand-Buck griping that salt licks were better when he was a fawn, and that yearlings have it easy crossing the road these days now that cars have antilock brakes.

Seriously though, life gets harder in many ways as organisms age. Ask anyone who retired to Florida why they left northern New York and they’ll probably tell you winters were enjoyable until arthritis and various other ailments set in. What happens to wild deer as they become senior citizens—do they succumb to age-related health issues like bad joints, decayed teeth, or tumors?

I put the question to retired New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) Wildlife Biologist Ken Kogut, who lives outside of Potsdam. He laughed. “To have a deer die of old age in the wild is an oxymoron,” he said. Ken went on to explain that in terms of hunting, NYSDEC data show the vast majority of harvested deer are in the 1.3 to 3.5 year-old range (because they are born in May and June, deer are always in a half-year by hunting season). “To see a seven or eight year-old buck [at a NYSDEC check station] is very, very unusual.”

To illustrate this point, consider that the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research states the average lifespan of captive white-tails is 16 years, with the confirmed oldest captive deer living to be an ancient 23 years old. Compare that to wild white-tails, which do not have a good track record, so to speak. The average lifespan of a wild deer? According to a University of Michigan report, two years. Yeah. Ten is considered the upper age limit, and a very rare occurrence at that.

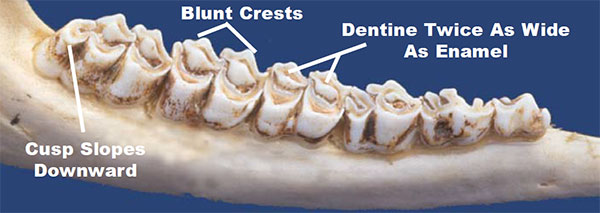

The typical tooth wear in a 4.5 year old white-tailed deer. Illustration: Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife

Determining the vintage of white-tails is called aging deer, not to be confused with the aging of parents, which is a function of both the number and activity level of their children. How do we find how many birthdays a deer has had? Dentistry.

White-tails have canine teeth (the irony of which, sadly, is lost on them) and incisors on the lower jaw, but none on the upper. In other words they can’t snip off a twig the way a rabbit can, but have to tear it away with an upward motion. But they do have upper and lower molars, and the wear on these is used to tell how old a deer is. Or was, as this is generally done post-mortem.

Aging deer started as kind of a home-grown citizen-science project. In years past, keenly observant hunters who could identify an individual deer from yearling stage onward took note of molar wear when it was harvested. Years of correlation of known deer age with measured teeth wear (turns out it’s one millimeter per year) made hunters like dairy farmer and NYS Big Buck Club founder Bob Estes of Caledonia, NY, expert in aging white-tails.

Aside from hunting, another thing driving down the average lifespan of wild deer is predation of fawns by coyotes and black bears. Surprisingly, in the Adirondacks, the latter actually kill more fawns than coyotes do. Predation is hard to quantify, though, as coyotes and bears eat every last vestige—bone, hair, and innards—of any animal they kill or find dead of other causes. Because predators do not feel safe out in the open, they don’t eat dead deer on roadsides, which are left to rot.

An estimated 65,000 white-tailed deer are killed each year along New York state roads. Photo: batwrangler, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Deer-vehicle collisions are another huge factor, with the New York State Department of Transportation reporting an average of 65,000 per year. But according to Kogut starvation during hard winters is probably the single factor likely to kill older deer. For various reasons including worn molars, they are likely to have less stored body fat going into winter than a younger deer.

With all this carnage, are white-tails disappearing? Hardly. Dr. Peter Smallidge, the State Forester for Cornell Extension, said that at the time of European settlement, it’s estimated there were fewer than one deer per two square miles in New York State, about 20,000 in total. Today there are two million, more than enough to destroy the ability of many forests to regrow, as young trees are devoured by deer while they are seedlings.

Lyme disease is also a result of deer overpopulation. Cornell Extension Wildlife Specialist Dr. Paul Curtis believes that if the deer population went down below six per square mile—still higher than the historic density—then deer ticks, which spread Lyme disease, would become too scarce to be a public health threat.

What might cause the deer population to decline like that? I don’t know, but it certainly won’t be from old age.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.