Bill McKibben’s first novel and a biography in poetry

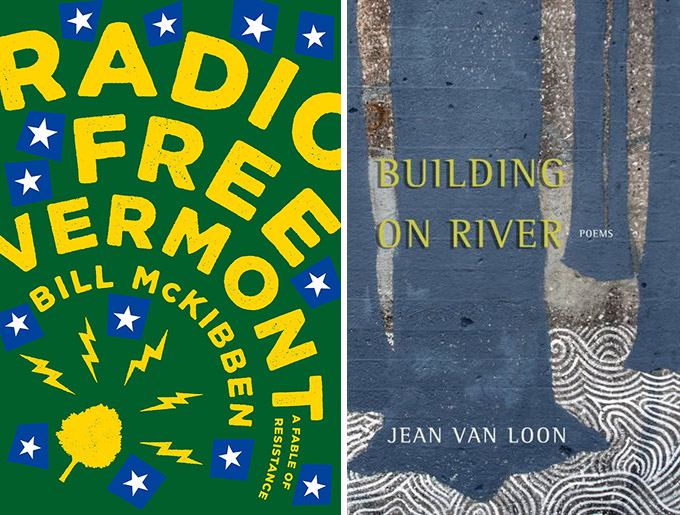

Book Covers: “Radio Free Vermont,” Bill McKibben, Blue Rider Press, 2017 and “Building on River,” Jean Van Loon, Cormorant Books, 2018.

Radio Free Vermont, Bill McKibben

Who would have believed that the ultra-serious Bill McKibben would write an almost slapstick novel? He gained fame with his first book, The End of Nature, a grim look at how climate change and human activity are changing, and ruining, the world. And most of his books since then have had a similar warning tone.

Not so with his first novel, Radio Free Vermont (Blue Rider Press, 2017). McKibben has fun imagining an unlikely team of Vermonters who are trying to change politics from the ground up, and engaging in some non-violent antics along the way. In the first chapter, a Coors truck enters Vermont over the Crown Point Bridge and detour signs direct it to a remote dead-end dirt road. When it stops people wearing black balaclavas appear out of the woods and one of them gives the driver a bag lunch, made with Vermont products, while the others unscrew the caps from six-packs and dump all the Coors on the ground.

The driver watched from his rearview mirror, and after about half an hour he finally spoke:

“Hey, lady. This is going to take forever—I’ve got twelve hundred cartons in the truck. Why don’t you just toss them over the side and let me go?” The woman looked up at him from above a draining carton of beer. “Oh sweetie,” she said. “This is Vermont. We recycle.”

McKibben freely admits he had help creating this novel from friends more experienced in writing fiction, including his novelist wife, Sue Halpern. The resulting book holds together well, in a slightly madcap way, and the characters are quirky and worth cheering for. Seventy-two-year-old Vern Barclay isn’t exactly a fictional Bernie Sanders (he’s a radio announcer not a politician), but he does gain a following when he broadcasts his ideas for making Vermont an independent nation.

My favorite character is Sylvia Granger, a woman who runs a School for New Vermonters. Each student, mostly wealthy retired bank executives who have retired to Vermont, must learn how to drive in the mud, how to use a chainsaw, and how to behave in Town Meeting. They also practice using firehouse and pumper trucks because they will, of course, volunteer for their new local fire department.

Don’t read Radio Free Vermont if you are looking for great literature. Do read it if you’d like a quick, fun read that also asks some big questions. What can we do to make our state and federal governments more responsive to the people? McKibben writes in his Author’s Note, “When confronted by small men doing big and stupid things, we need to resist with all the creativity and wit we can muster, and if we can do so without losing the civility that makes life enjoyable, then so much the better.”

Building on River, Jean Van Loon

My next book choice brings readers to Canada, and the nineteenth century. Jean Van Loon’s book of poems, Building on River (Cormorant Books, 2018), tells the rags-to-riches story of John Rudolphus Booth, 1827-1925. Van Loon includes one page of text outlined Booth’s life and the rest of the book is poetry. This creates a surprisingly moving story about a man born on a small farm in Ontario who came to Ottawa to make his living and who by the end of his life owned the largest sawmill in the world, as well as a couple of railroad lines and thousands of acres of woods.

Before Booth died he burned all his private papers but Van Loon ferretted out other sources to use in her poems. She has a poem, “Fire Trains” about the fire in 1900 that devastated most of the riverside homes and factories in what was then called Hull, now the Gatineau. Here’s a middle stanza:

The sweet-bitter stink of charred wood

rises from the 400 acres of burn

whirls across the Upper Town to Parliament Hill

in gusts from the South

across the flat lands of Nepean farther than eye can see

when long blasts sweep from the North.

Though Booth lost his own home and many other buildings his sawmill did not burn because his second son, Frederick, “the glad-hand,” had invented a sprinkler system that he insisted they install.

A poem about the effects of sawdust dumped in the Ottawa River is dramatic. A fisherman dies when a bubble of trapped methane explodes and throws him out of his boat. Here’s the ninth and last stanza:

In 1951, Princess Elizabeth will cruise the Ottawa.

A lady reporter —-stepping, she thinks, ashore —

will sink through debris to the bottom.Engineers of the 1960s, preparing footings

for the Macdonald-Cartier bridge

will dig into sawmill waste three metres deep.

Van Loon’s poems are not flowery or academic. I’ve haven’t read her other work, but this straightforward style works well for this biography. I read the book in one sitting and felt I’d briefly entered the life and times of a fascinating Canadian man.

Tags: book review