When they handed the brains out

Size matters, sorta. Illustration: CNX OpenStax, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

When the topic of animal intelligence comes up, we might argue whether a crow or a parrot is the more clever, or if dolphins are smarter than manatees. Seldom do we ascribe smarts to life-forms such as insects, plants or fungi. And it is rare indeed that we question our intellectual primacy among animals. It is true that no other species can point to monumental achievements such as the Colosseum, acid rain, nerve gas and atomic bombs. But that does not mean other species are bird-brained. Metaphorically speaking.

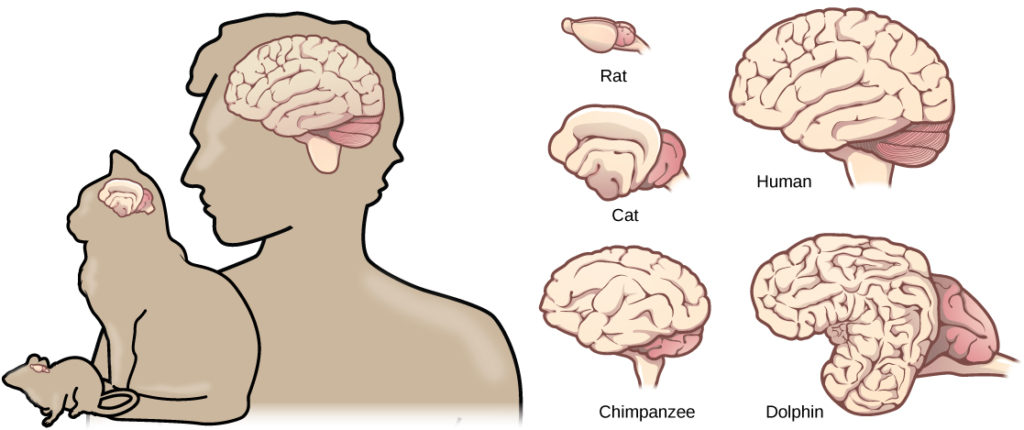

It makes sense that elephants and whales are whiz-kids, given the size of their heads. Depending on species, whale brains weigh between 12 and 18 pounds (5.4-8 kg.), and Dumbo’s cranium would tip the scale at around 11 lbs. (5.1 kg.). Compared to them, our 3-pound (1.3 kg.) brains are small potatoes. What sets mammal brains apart from other classes of animal is the neocortex, the outermost region of the brain responsible for higher functions such as language and abstract thinking.

But size is not the only thing that counts. Our neocortices, unlike those of most animals, are highly convoluted, which means we make everything way more complicated than necessary. Actually, convolution gives our brains a lot more real estate by volume—as if Texas were a rug and it got scrunched up to the size of Vermont. A lot of acreage would fit in a small space if it were nothing but valleys and mountains. This greater surface area equates to more processing power than a less highly folded brain like a whale’s.

The ability to make and use tools, and to carry them for future use, is one of the widely accepted indicators of intelligence. In the past, it was thought that only humans and our close ape relatives used tools. Some gorillas in Borneo use sticks to spear catfish, and western lowland gorillas have been observed using a stick to gauge water depth. In at least one case, a gorilla used a log to fashion a bridge to cross a stream. I suppose if they started charging a toll, we would give them more respect.

Only just recently has the intelligence of cephalopods like cuttlefish, squid and octopodes been documented. Octopodes have been observed foraging for discarded coconut shells and using them to build sea-castles of sorts in which to hide. If their ability with tools progresses, I bet they could knit an awesome sweater in no time.

A wild New Caledonian crow is using a stick tool to probe for insects in the top of dead trees. Photo: Natalie Uomini, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Birds also use tools—crows, for example, will use a stick to poke at bugs they can’t otherwise reach. When the insect bites the stick, the crow pulls the stick out and eats the bug. Humans always assumed birds were not very smart because their brains weigh a few grams, and range from pea-size to maybe the size of a walnut. Well, we’ve had to eat crow, because bird brains are far more neuron-dense than mammal brains. It’s like we were comparing the microchip brain of birds to the big vacuum-tube human brain and sneering, when in fact many birds test on par with primates for intelligence.

We know that honeybees use a sort of interpretive bee-dance to communicate with each other as to the location of flowers and picnickers. Our native bumblebees seem to have one up on them. In 2016, researchers at Queen Mary University of London found that bumblebees learned within minutes how to roll a tiny ball into a little hole to get a sugar-water reward. I assume the researchers are now busy with bumblebee golf tournaments.

Even vegetables can learn new tricks. Experiments have shown Pavlovian responses when light and other stimuli are presented together from various angles. Plants of course will grow in the direction of light. But when the light was switched off, the plants tilted toward the other stimuli, just like the way Pavlov’s dogs salivated when they heard bells. I imagine the winter holiday season was frustrating for those drool-pooches.

Humans, apes, squids, birds, bugs, and plants—there’s nowhere to go but down. Enter the plasmodial slime mold, a slow-moving single-cell organism that can scout the landscape, find the best food, and engulf it, growing ever larger. Coming soon to a theater near you. It sounds like a sci-fi film, and a blob of pink, yellow or white slime mold, possibly a square yard in area, does look pretty alien. They usually live in shaded forest environments, but can show up on your flower bed, and a friend once sent a picture of a slime mold which had engulfed his empty beer can left out overnight.

Even Fuligo septica, the lamentably nicknamed “dog vomit” slime mold gets credit for using complex algorithms to make decisions. Photo: Siga, public domain

Researchers discovered that a plasmodial slime mold uses complex algorithms to make decisions—logical ones, it turns out—regarding which direction to proceed as it slimes across the landscape. One of the lead researchers in the 2015 study is Simon Garnier, an Assistant Professor of Biology at New Jersey Institute of Technology. He said that “[studying slime molds] challenges our preconceived notions of the minimum biological hardware required for sophisticated behavior.”

Maybe it’s time we paid more attention to our non-human relatives. I bet they have a lot to teach us.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Tags: animal intelligence, biology, brains