Slow-mo horror show: It’s plasmodial slime mold!

Fuligo septica, the pleasantly nicknamed “dog vomit” slime mold. Photo: Siga, public domain

Imagine if you ventured out on a rainy afternoon and found a bright yellow slime-blob slithering across your perennial gardens, one that was not there the previous day. Let’s say this amoeba-like thing was growing larger by the minute as it dissolved and consumed organic matter it encountered on its way through your yard. You might look around for Steve McQueen and the rest of the cast of the 1958 classic horror film “The Blob,” right? Just before you called 911.

While it sounds like fiction, this scenario does happen (minus Steve McQueen et al) during periods of wet weather on mulched beds, in the woods, and other places with abundant organic matter. Of course there are some key qualifications to the above description. The blob, called a plasmodial slime mold, is slimy, but not a mold. What it is, precisely, may be still up for debate.

Fortunately this freak of nature moves slowly—a foot per day at most—and there is an upper limit to its size, maybe twenty inches across. Also it engulfs things like bacteria and rotting vegetation—you need not worry about pets and small children near a slime mold.

It is a tired cliché that things were simpler in the past, but in some ways it’s true. When I was a kid you had three television stations, one kind of phone, and only two options when you ordered coffee. I don’t claim it was better, but it was simpler for sure.

And in the great outdoors if you found some living thing you didn’t recognize, there were three possibilities—it was either an animal, plant, or fungus. Animals were relatively big and could move around, plants did not travel and were usually green, and fungi grew on decaying wood and behaved themselves. Single-celled organisms didn’t really count because you couldn’t see them. It’s not that simple today.

In high school I learned about the five divisions of living things, three of which were microbial. Soon after, it got switched to three domains, and now the powers-that-be (ever wonder who exactly they are?) tell us there are six kingdoms of life-forms. This will undoubtedly change again next week, so don’t fret about it.

As their category-waffling suggests, taxonomists argue a lot. Over the years, the plasmodial slime mold has given them much to provoke disagreements. A single-cell organism, a slime mold may live its entire life as a solitary and immobile microbe. But if conditions are right, it will start gliding across the landscape, engulfing other slime-mold cells in addition to organic matter, and growing to pancake-size. It does this while remaining a single cell, albeit one with millions of free-floating nuclei from all the hapless slime mold organisms it ate.

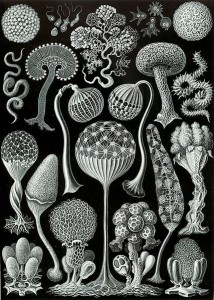

They’re a little prettier in the microscope. Illustration: Mycetozoa from Ernst Haeckel‘s 1904 Kunstformen der Natur (Artforms of Nature)

Long considered fungi, slime molds are now lumped in with protists, a category which is more or less the “island of misfits” for microbes. Protists are a varied lot—some are pathogens that cause malaria, sleeping sickness, giardiasis, and other nasty illnesses, while some are innocuous, for example algae and slime mold.

Ranging in color from brown, white, or blue-gray to brilliant yellow, slime molds have been mistaken for dog vomit, and in some places are known as demon puke. Not exactly endearing, but they do help recycle nutrients in the environment. And it’s not their fault they’re so common.

Here in the Northeast we now get something like three more inches of precipitation than we did forty years ago. In addition, our “new normal” weather patterns include long blocks of wet. Sadly, these conditions are ideal for plant pathogens, but they also favor slime molds, which you are as likely to see growing on wood-chip mulch in suburbia as in the forest.

When conditions dry out, a slime mold’s plasmodial, or “Blob” days are over. It stops and makes spore-bearing structures that look like stalked mini-puffballs, some of which can be quite colorful. You can find some intriguing pictures online. Of slime molds, I mean.

Like some of us, the 1958 Blob was rendered inert by extreme cold. In the movie it was airlifted to the far north where, as McQueen’s character explained, it will no longer be a threat to humans, “as long as the Arctic stays cold.” Uh-oh. Maybe we should start carrying ice packs, just in case.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Your comment about more rainfall in the northeast reminded me of powder post beetles liking a certain humidity and they are now in my barn-and my previous porch roof delaminating because it lacked vents.

I have seen the yellow slime mold, brilliant yellow- cool.

Thank you Paul, for this piece. Anyone who knows me knows that this is one of my favorite organisms!