Frog music: warming up the organs

Every spring, Mother Nature takes the choir out of the freezer. And sometimes, this year for example, she pops them back in for a while. The choir to which I refer is that all-male horde of early-spring frogs: spring peepers, wood frogs, and chorus frogs. Even while an ice rind still clings to the pond edges, untold numbers of these guys roust themselves from torpor to sing for female attention.

While in our species it is mostly an inflated ego which causes males to become unusually loud attention-mongers when seeking mates, it is an inflated vocal sac which allows male frogs to be so noisy. This air-filled structure balloons out tight, acting as a resonance chamber to amplify sound. I don’t know how it is with all frog species, but the inflated vocal sac of a peeper is almost as big as it is. This contrasts with the human male, whose ego can sometimes swell to many times his body size.

Spring peepers (Pseudacris crucifer) are the most vocal of the trio, and their song is the most widely recognized. I’d describe their call as a sweet, shrill—let’s see—peep, shall we say. Singly or in small groups it is melodious, and a large population of them can be deafening (some people with atypical hearing ranges describe it as painful).

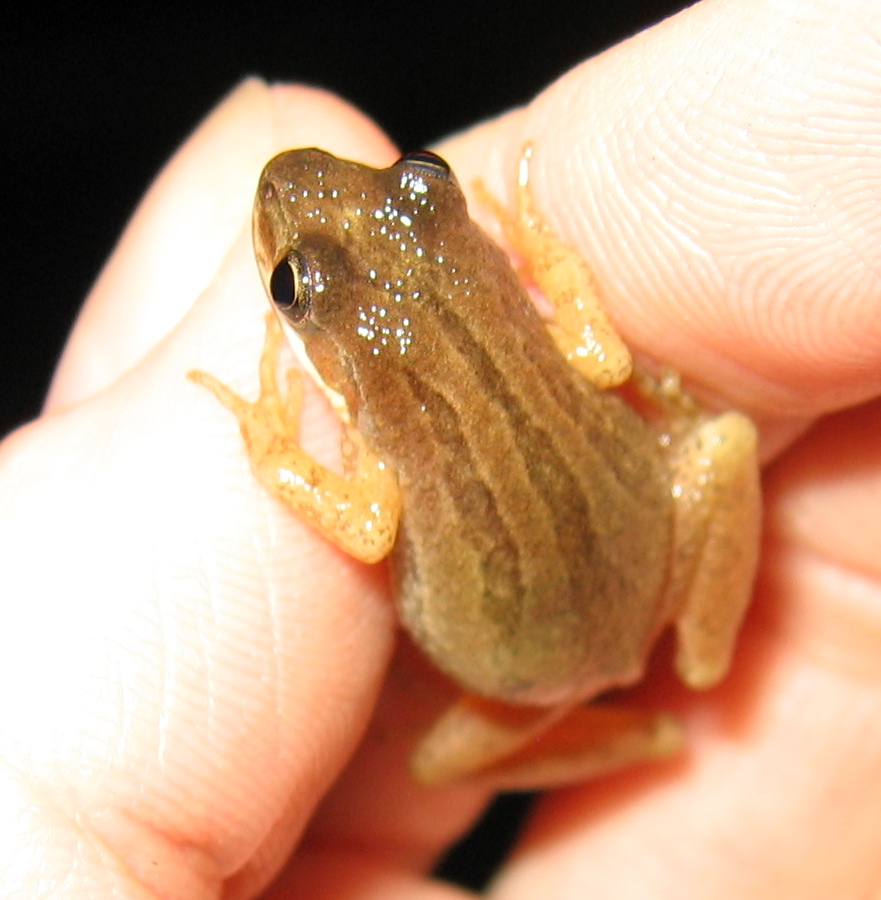

The rough “X” (or cross; hence the species name) on their backs help identify this tan, inch-long amphibian with toe pads similar to those of a tree frog. Peepers can in fact climb trees, but for whatever reason they seldom do. Maybe there is no need to climb because they can practically fly. Peepers can jump 40 to 50 times their body length.

If it quacks like a duck, it’s not always a duck. Wood frogs (Lithobates sylvaticus) are plenty vocal, although their calls don’t carry as far as other frogs’ do. Their call is a short quack, not so much like they are imitating a duck call, but more like they are inspired by it. I have sometimes thought it sounds like barking, but that may be a minority opinion.

A wood frog sits patiently on the ice of a pond in Lake Placid’s Intervale Lowlands. It will breed as soon as the ice melts. Archive Photo of the Day: Larry Master

As their name indicates, wood frogs spend considerable time in the forest, wintering over in the leaf litter, and breeding in shallow ephemeral pools in the woods. Measuring around 2 ½ inches long, they are brown to copper-colored, with a raccoon-like dark mask across their eyes.

Every time I approach a group of wood frogs in early spring I am tempted to set up a curtain or something so they can have privacy. Let’s just say they are rather animated and communal in their business dealings, in addition to being very public. Wood frogs create large collective egg masses, apparently not a common practice in the frog world.

If the frost is more than a few inches deep, both spring peepers and wood frogs freeze solid during winter. Obviously they have some kind of super-powers, namely that they pump cellular water outside of the cell walls. They also produce antifreeze to help prevent tissue damage at below-freezing temps.

It turns out that among other chemicals, they create ethylene glycol, the same thing you put in your car radiator. If more than a quart of this compound is released into the environment, it’s considered a “reportable quantity,” and therefore a hazardous spill that must be disclosed to regulators. I don’t know how many winterized peepers or wood frogs it would take to constitute a quart of ethylene glycol, but good luck getting them to register with the EPA, right?

Pseudacris kalmi, the boreal chorus frog. Photo: Anita Gould, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

The choir wouldn’t be complete without the aptly named chorus frog. Our boreal, or upland, chorus frog (Pseudacris kalmi) is one- to 1 ½- inches long, greenish-gray to brown, with three dark stripes down its back. More or less the backup singers for spring peepers, their call is a melodious, trilling “crreeek” that lasts a second or two. Listen for this understated song amidst the nonstop cacophony of peepers.

If you’ve ever run your fingernail along the teeth of a cheap, hard-plastic comb, you’ve approximated their call. Go easy on the comb, though, or you may have female chorus frogs following you around.

When dormant animals are roused from torpor several times before spring actually arrives, it is hard on them. Finding appropriate shelter, in the case of chorus frogs, and preparing to become frog-sicles in the case of peepers and wood frogs, takes energy. Since there is little to eat yet, they are still relying on energy reserves from the previous year. Going back under the spell of the Ice Queen once is probably not an issue, but if it were to happen repeatedly it could cause undue stress. I say we try and distract Ma Nature long enough for someone to sneak in and unplug her freezer.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.