Ottawa’s new National Holocaust Monument

Not a sunny subject

I try to make my weekly Canadian stories somewhat entertaining. This week’s story is somber, and it’s supposed to be that way. The National Holocaust Monument was officially opened by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on September 27. It’s located west of Parliament Hill and the downtown area at the corner of Wellington and Booth Streets, across from the Canadian War Museum.

I visited it on a cool, cloudy day. At first, I thought about waiting until a day when it was warm and sunny, but then I thought, this is not a warm and sunny subject, no matter the weather. Grey skies and cool air are better for fostering respect and remembrance.

How the monument came to be

Until now, Canada was the only allied country from World War II without a national Holocaust monument. There are however, other Holocaust memorials and museums located in communities across the country.

The effort to establish an official national monument did not come from anyone with a personal connection to the Holocaust. In 2011, Member of Parliament Tim Uppal, a Conservative, practicing Sikh from Alberta, introduced a bill in the House of Commons to establish the monument. It passed through the House and Senate and became law.

“Prayer Room” by Edward Burtynsky is one of several of the artist/photographer’s works embossed onto the concrete walls of the National Holocaust Monument. This image depicts a space for prayer that Jewish prisoners in the Theresienstadt ghetto in what is now the Czech Republic managed to create, even though they were imprisoned for their beliefs at the time. Photo: James Morgan

The National Holocaust Development council, composed of business people and clerics from Jewish communities across Canada, was formed to fundraise and oversee the design of the monument. A team led by noted Toronto museum planner Gail Lord was selected. It included Polish-American architect Daniel Liebskind, whose recent work includes the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan and the Michael Lee Chin Crystal at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, and Canadian artist/photographer Edward Burtynsky, whose work is featured at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The design team’s plan was called Landscape of Loss, Memory, and Survival. An aerial view of the monument depicts a Star of David, which is not only the most identifiable symbol of Judaism, but is also meant to represent the yellow Star of David badges the Nazis forced Jews to wear in ghettos and death camps. The monument has no roof, yet it has enclosed spaces and narrow passages. A small room offers space for reflection and a flame, recessed in one of the walls, burns in honor of victims. There is space for 1,000 people in the center of the monument for remembrance ceremonies.

Errors and omissions

Canada has an uncomfortable past with the Holocaust. Government officials were well aware that it was happening during the 1930s and 1940s. However, anti-Semitic sentiment within the government of Prime Minister Mackenzie King and among the public at the time got in the way of Canada acting in a meaningful way to help people escape the Nazis.

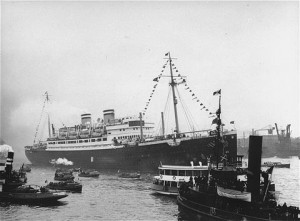

In 1939, the German ocean liner St. Louis left Hamburg with over 900 people, mostly Jews aboard, who were trying to escape. A small number were allowed in Cuba but most were denied. Efforts to seek asylum in the United States, and then Canada, were unsuccessful. St. Louis returned to Europe. Most of the passengers were allowed to reside in Belgium, while others were admitted to the United Kingdom, France and The Netherlands. The ship returned to Hamburg without any passengers. Unfortunately, Belgium, France and The Netherlands fell to the Nazis in 1940 and one quarter of those who had been aboard St. Louis ended up dying in Hitler’s death camps.

Canada’s post-war response was better. An estimated 40,000 Holocaust survivors were admitted. Prime Minister Trudeau has stated that the government is planning an official apology for refusing to accept the people aboard St. Louis and for the anti-Semitic sentiment of the government at the time.

The fact that the largest group who died in the camps were six million Jews gives how the Holocaust is commemorated much of its character. While other faiths and groups were targets of the Nazi extermination program – homosexuals, Roma gypsies, Jehovah’s Witnesses, the disabled, Russian POWS – the effort by the federal government to include every sort of person who could have been a victim led to a significant omission at the new monument in Ottawa. The plaque dedicating the monument completely left out any mention of the Jewish people.

Conservative Member of Parliament David Sweet recently raised the matter in the House of Commons. Stopping anti-Semitism has been a major cause for Sweet. “If we are going to stamp out hatred toward Jews, it is important to get history right,” he said. Heritage Minister Melanie Joly apologized for the omission and said that the plaque has been removed and will be replaced.

Take time to visit the National Holocaust Monument in Ottawa. It is a painful reminder of a past tragedy. But, it is a place to remember, reflect, and develop a spirit of resolve to ensure such a horrible event is never forgotten, or repeated.

Tags: canada, Holocaust remembrance, National Holocaust Monument, ottawa