Green Eggs and Lamb

A Tofurkey roast. Photo: Aine, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Due to recent events, I’m now the only non-vegan member of a household. Granted it is a household of two where my omnivore status is respected, but the adjustment has taken longer than expected. It was some time before I stopped worrying about the welfare of tofu animals and was able to buy tofu turkey, ham, and sausage without suffering pangs of guilt.

Although we may not think of eating as able to change anything except our waistline, choices around diet do have serious and far-reaching consequences across the world. Volumes have been written on the human rights, energy policy, health, and environmental implications of food choices. But distilling even one of these points to a digestible portion-size requires more than just an essay.

Today we are rightly concerned about the way dietary decisions affect the rate of global warming, the cause of climate change. We know that eating locally sourced meat and produce uses less energy than buying food shipped from across the country, or imported from abroad. And that adhering to a plant-based diet produces much less carbon dioxide and methane as compared to one where meat features prominently. While there are many compounding, mitigating and plain old confusing factors to consider, it is a conversation well worth starting. And all the more important to continue.

During the Middle Ages, Europeans had other sorts of dietary concerns. Before New World crops got established in Europe, the main food issues were the involuntary fad diets of malnutrition and starvation in vogue at the time. Today, about 60% of food grown in Europe – indeed worldwide – are crops first developed by Native American agronomists.

The “Three Sisters,” corn squash and beans, are planted in the lower right of this garden plot. Photo: Christian Guthier, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

As corn, potatoes, sunflowers, beans, tomatoes, amaranth, chestnuts, squash, and other Native American crops spread across Eurasia, it helped push starvation a few inches away from everyone’s doorstep. In part due to this extra breathing room, novel dietary worries developed. Such as whether a sheep that grows on a vine is a vegetable or an animal, or if birds which develop inside pods that grow on trees were OK to eat on meat-free Christian fast days.

For hundreds of years, a succession of learned men debated this, rather than more appropriate questions such as “Is this merely silly, or totally nuts?” The idea that you could plant a garden of tree-pod birds and vine-lambs, maybe even a cabbage-patch kid, did not seem to bother guys who fancied themselves the smartest people in the world.

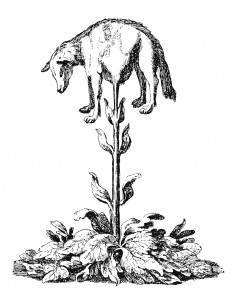

The origins of the vegetable-lamb tale are a bit woolly, but may date back 2,500 years. The widely traveled Greek historian Heroditus is said to have mentioned it in 442 BCE. But he was 17 at the time, so who knows which exotic plants he saw, and which he ingested or smoked. Evidently, a Jewish fable ca. 500 CE also makes reference to a livestock-on-a-stick “vegtimal.” From the 14th century through the late 1700s, Europeans made expeditions into poorly mapped regions of central and northern Asia to locate this vegetable sheep.

Upon return, scholars wrote in detail on the new species they almost, but not quite, found. It was dubbed the Scythian or Tartary lamb after the regions the travelers believed they’d visited. It was also called the Barometz (various spellings), possibly from a word for lamb in one of the languages they encountered.

In the 1357 memoir The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, the author (a pseudonym) is said to have regaled King Edward III of England with a description of a gourd-like fruit that one sliced open to reveal a flesh-and-blood lamb (sans wool) which could be eaten as any normal lamb. I wonder if it was seedless, or if you had to chew carefully and spit out sheep-seeds. Later explorers depicted the lamb growing on a stalk or vine which connected to its navel like an umbilicus. The lamb could graze around the plant, but if the umbilicus-stalk broke, it would die. I assume these men also located a now-extinct carnivore of exceeding stupidity which could not understand how to hunt sheep tied to the ground.

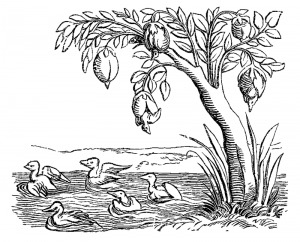

Illustration: Barnacle Geese,from the “Cosmographie Universelle” of Munster, folio, Basle, 1552, public domain

Asceticism may cause hallucinations. In the 11th and 12th centuries, a number of clerics in remote, barren monasteries in the northern British Isles swore they saw trees whose pods dropped into the ocean and turned into “Bernacae” (barnacle) geese. Logically, those geese could be eaten on mandatory fast-days when real, non-plant meat could not be touched. Pope Innocent III eventually ruled that though some geese grew on trees, they were still off-limits on Fridays. Because the Pope did not visit rocky clifftop enclaves, “meatless” geese dinners continued in some areas into the 20th century.

The real-life barnacle goose, Branta leucopsis, breeds in the Scottish Hebrides, on Ireland’s northwest coast, in Greenland, and in other North Atlantic locations. They are more secretive than other geese and waterfowl in their breeding habits, favoring high cliffs as nest sites. As a result, fledged juveniles seem to come out of nowhere and appear on the water.

Green lambs exist, of course. Native to the Malay Peninsula, Cibotium barometz, the golden woolly fern, has a chunky and unusually tomentose (woolly) surface rhizome which can be roasted, and its starchy insides eaten. There are neither bones nor seeds. Related ferns with similar features grow elsewhere, including New Zealand, and have also reportedly been used for food.

Were it not fiction, vegetable-meat would go a long way toward reducing world hunger, greenhouse gas emissions, and maybe domestic squabbles. But I respect and support my vegan partner, and she does not try to “recruit” me away from omnivorism. I eat more legumes than before, but plan to continue enjoying moderate amounts of local meat. Hey, even Mary had a little lamb, or so we are told.

Paul Hetzler is a horticulture and natural resources educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of St. Lawrence County.

Tags: diet, environment, mythology, nutrition