Major update to British rules of succession

Blame the Normans, after William defeated Harold in 1066

“Primogeniture” is a seldom-used word. It crops up now because royal succession is making headlines – as with the widely-reported news that Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge is expecting her first child.

Although I’ve met the word as a reader of history-themed material, I’ve always been reluctant to say it aloud.

Modern resources to the rescue, as with this entry from Aug 13, 2012, of the New York Times “The Learning Network/Word of the Day”, which included linkage to something called the Visual Thesaurus.

After listening to the proffered audio closely, my phonetic rendering would go something like: “prime-oh-jen-it-tour”. (Just like it looks, right?)

The word is commonly used to mean a right of inheritance that belongs exclusively to the eldest (legitimate) son.

A reader’s comment in the above-mentioned NYT link took issue with the implication that the word itself favors males:

What you’ve described above is “male-preference primogeniture”.

“Primogeniture” itself is gender neutral, and simply refers to the firstborn child.

There can be “equal primogeniture”, “female-preference primogeniture”, and “male-preference primogeniture”, amongst other types of succession.

— Will Bower

Anyway, the rules of succession for the British monarchy are being changed to abandon male-preference primogeniture.

By the time William and Catherine’s first-born arrives, that baby – girl or boy – shall be next in line for the throne, after Charles and William, that is.

Mind you, saddling an innocent baby with a high-profile job for life strikes me as a profoundly tragic fate. (Indeed, some truly unfortunate events surrounding media intrusion have already transpired this week.)

But back to succession rules. To illustrate how big a shift this will be, consider the current Queen, Elizabeth II. The eldest child of King George VI, Elizabeth was the “heir presumptive” because if her parents ever had a son, the boy would supplant both older sisters in line of succession.

Elizabeth became queen 60 years ago. She and her consort, Prince Phillip, had four children. In order of birth: Charles, Anne, Andrew and Edward. Though second oldest (and easily equal to her brothers by most measures of ability) Anne could only become Queen if all of her brothers (even the younger two) and all of their children (or grandchildren) died first.

Basically it’s a system where girls will do, in a pinch. But up to now – compared to boys – they really were chopped liver.

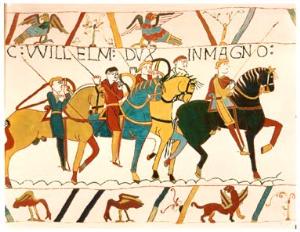

Great Britain passes thrones and great estates along that way because the Normans conquered England back in 1066 and they believed in male-preference primogeniture. While many cultures followed different rules of inheritance, the Norman model was very useful for concentrating wealth and power into ever-larger and more important holdings.Here’s a list of kings and queens of England and (later) Great Britain. The most famous example of son-hunger in English monarchy is personified by Henry VIII – he of six wives, only one of whom could produce a son that survived infancy.

George the III (king during the American Revolution) and his wife Sophia had an impressive fifteen children. But their granddaughter Victoria eventually became Queen because not one of George III’s nine sons could produce a legitimate male heir.

Stepping away from royal succession, primogeniture meant so-called second sons among nobility and gentry had to strike out in other fields – join the church, go into the army or marry for money, etc. Colonies abroad became grand places for younger sons, something that helped early American and Canadian settlement.

On the whole, a good marriage was the best women could aspire to. The related practice of entailment, and its effects on inheritance and society across centuries, is discussed in a fairly readable manner in this essay by Luanne Redmond called “Land, Law and Love” by way of the Jane Austen Society of North America.

Current rules on succession and marriage for British royalty date back over 300 years, and still include a ban on becoming or marrying a Catholic. That prohibition may sound silly today. But it was meant to resolve a long history of strife back when Protestants and Catholics jostled for primacy with bloody, ruthless intolerance.

Under the new rules, an heir or ruler would henceforth be permitted to marry a Catholic. But the monarch cannot yet be Catholic as she or he must also be the Supreme Governor of the Church of England.

Consider that detail about church and state in contrast to the U.S. Constitution, which explicitly says: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”. In England there was (and is) an established state religion.

The non-establishment clause strikes me as a great leap forward. (Next time someone wishes the U.S. was officially Christian ask how they might feel if the “wrong” kind of Christianity happened to be the state-sanctioned faith.)

It is worth noting the Queen’s heir, Prince Charles, has advocated changing the monarch’s title “defender of the faith” to “defender of faith” (to mean faiths, plural). An interesting proposal but there’s been little movement in that direction to date. (The days are long gone where a monarch got to dictate such things at will, as Henry VIII once could.)

Readers who don’t care wandered off with eyes glazing over after my first few sentences, bored with silly dead-ends of history. But some people actually follow this minutia, as reflections of older, larger pictures.

There are official lists of succession, and whimsical articles about who ranks where. The Wall Street Journal has even identified a woman it calls last in line of the current eligible crop (“4,973 in line as of 2001”).

Meanwhile, not everyone favors the upcoming changes. Witness this heartfelt rejection of the proposed reforms from one A. P. Schrader, who writes that monarchy itself discriminates (for a purpose) so don’t mess with it! Medling with tradition skirts a slippery slope:

We should also be very wary of handing Parliament a precedent that says they can tinker with the succession to amend anything they see as an “anomaly”. Must we concede the point that it is wrong to discriminate against women? Okay, fine. But, if we accept that logic, then we must ask ourselves why is it legitimate that a girl succeeds just because she is ‘older’ than her younger brother. Surely age is an equally subjective criterion? Do we not frown upon ‘ageism’ in our society? Maybe, if we are going to start down this road, we should cut out a lineal succession as well. Why not let the smartest heir succeed? We could get them to sit a test to determine which one was the most suitable. Perhaps a beauty contest might be preferable. We should pick the best looking one. After all, we want our Sovereign to be photogenic, don’t we? Don’t want an ugly person on all those stamps, coins and banknotes. Maybe we are not particularly impressed with any of the children. Why not let a cousin succeed? Why not look outside the Royal Family altogether? Uh oh! Hang on a sec’. What’s happened? Oh dear, we’ve acquired a republic by stealth. Reforms like this are – to use that tired old cliché of ‘Sir Humphrey’ in Yes, Minister! – the “thin-end of the wedge”.

The Monarchy in the Netherlands dropped their boys-first rule for royal inheritance back in the 1980’s.

Japan’s preference for a male ruler runs long and deep. The lack of a male heir among the younger generations seemed critical enough to contemplate changing the law to permit the Crown Prince’s only daughter to inherit. But then the Crown Prince’s younger brother had a son in 2006 and the idea was dropped. (Note: Independent-minded females would do well to avoid marrying into the Japanese royal family – where tradition weighs heavily against attempts at modernization.)

Of course, precious few have any personal stake in yon rarified landscape. Who becomes an earl, a duke or a royal heir is largely grist for mills of law, precedence and heraldry.

The current British monarchy is also a relatively young import, compared to England’s oldest noble families. They have “re-branded” before, as when the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha became the House of Windsor in 1917 because of anti-German sentiment during WW I. Indeed, as Time Magazine points out, adaptation has helped ensure this monarchy’s survival. Meanwhile…

…the English aristocracy has shown no signs of changing its laws of primogeniture that put young lords before ladies. (Retired University of London history professor Roger Lockyer) …says it is typical of the royals to strike out in a different direction from the English peerage

Still, the new royal succession rules represent a big change to something that once ran Anglo-influenced societies.

William and Catherine will not enjoy much private peace as they become new parents. But having children ranks among life’s greatest joys.

I wish them that pleasure, at least, in good health and with as much happiness as the constant glare of publicity permits.

Tags: history, inheritance law, Monarchy, Primogeniture, rules of succession, William and Catherine

I’ve always been fascinated by Americans’ seemingly never-ending interest in the British monarchy. The historical connections and links between the two countries are deep and important from an academic viewpoint but I’m amazed at the level of gossip column style interest. That type of interest is responsible in large part for the excesses we’ve debated elsewhere.

I agree with (the original) Larry. Gossip column fascination for British royalty in the U.S. seems odd.

In Canada – still a constitutional monarchy – the question of succession actually matters, technically.

Even if it’s a bore to average folks, the proposed change has to be dealt with in legislative spheres.

I’d leave it for the legal experts to say if all 16 commonwealth nations must agree, in unison. (It seems to me each could decide individually, though dissent could require leaving the commonwealth.)

Ottawa Citizen columnist Janice Kennedy says Canada has yet to formally pass the measures needed to approve gender-neutral succession. She points out those sort of procedures have a history of getting seriously bogged down in this country.

Kennedy goes further, saying the prohibition on a monarch being Catholic ought be struck down too. And/or the whole model of using a monarch as Canada’s head of state should be re-thought.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper, by word and deed, has shown notable support for the monarchy. If formal Canadian support for the proposed gender change can be done quickly and easily, this is the Prime Minister most inclined to make it so.

If it morphs into something stickier, well, so be it.

Canada doesn’t have enough clout to tell the Brits how to run their own monarchy. Nor would that be inappropriate.

But Canadians certainly have the right to debate what system will (or will not) be acceptable for Canada. If anyone has the stomach to go there, that is.

I find it interesting. Brian makes good point about the established Church of the State. Consider the condition of the Church of England, consider that Prince Charles is to be the Defender of the Faith? Churches should see that the last thing you want is to be declared the official state church!