Kingston Penitentiary closes with a charitable flourish

Kingston Penitentiary. Photo: Sean Marshall, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

What are the most famous – or notorious – prisons in the U.S.? Alcatraz? Sing-sing? Attica?

Well, in Canada, that distinction seems to belong to a penitentiary opened in 1835, right on the scenic lake shore of Kingston, Ontario.

You may not have heard of Kingston Penitentiary’s most famous inmates, but Canadians can collectively shudder when they think of convicted murders like Paul Bernardo, Clifford Olsen or Russell Williams. Here’s a short who’s-who of infamous inmates incarcerated there over the last 178 years, as compiled by Maclean’s Magazine.

This detailed story from the annals of CBC delves into the dark corners of the facility’s history, back when even children might see hard jail time.

The original rules for inmates stated that inmates “must not exchange a word with one another under any pretence whatever” and “must not exchange looks, wink, laugh, nod or gesticulate to each other,” with violators receiving the lash.

The original facility was a single, large limestone cellblock with 154 cells in five tiers. Those cells were 74 by 244 cm in width and 200 cm in height.

The three other wings of the main building were completed by the 1850s and the dome that connects the four cellblocks was added in 1861. It was then the largest public building in Upper Canada.

I think that cell size converts to roughly 29 by 96 inches of floor space with 79 inches of headroom. Ugh! The article includes a link for a 360 degree view of the interior of the grounds, and an interview with architectural historian Jennifer McKendry on the building’s significance. (Sorry to say this is “geo-fenced” for Canadian viewing only.) Here’s a time line of the penitentiary that should be accessible to all.

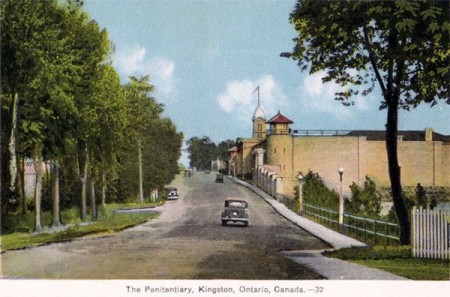

Kingston Penitentiary postcard, c. 1930. Photo: Bill Stevenson, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Women were moved out to their own prison in the 1930s. Like it or not, prisons elicit all kinds of morbid curiosity, including the question of executions. And here’s what I found on that:

While capital punishment was legal in Canada until 1976, it was only practiced until 1962. Capital executions were never carried out at Kingston Penitentiary itself, as executions were carried out at county or provincial jails.

According to that link, two inmates who killed a KP guard in an escape attempt were executed – elsewhere – for that crime in 1949.

With most inmates now transferred to other facilities, Kingston Penitentiary will officially close September 30th. I, too, am curious about where those prisoners all went and how that was determined, but that’s research for another day.

As was mentioned by Martha Foley on Thursday’s Eight O’Clock Hour, the last hurrah for the prison as such will be public tours from October 2-20. Those are being offered as a fund raiser for the regional United Way. (That ticket sale site has a tantalizing statement that “Minimum-security work-release-offenders may still be working onsite”. )

Unfortunately for many, those tours have completely sold out. Numerous news outlets are reporting keen interest in attaining tickets. A tricky wicket, with explicitly stipulations that tickets may not be re-sold. Writing in Thursday’s Kingston Whig-Standard, Peter Hendra recounts the difficulties organizers are coping with in the face of overwhelming response. (A faint hope for the most interested might be to volunteer to help give the tour.)

Perhaps this is a good time to mention an also-ran option: Canada’s Penitentiary Museum. It’s just across the street to help the curious grapple with this subject.

Debate continues about what to do with the prime waterfront property down the road. Back in 2012, at least, news accounts like this one by the Globe and Mail indicated it would be sold:

The site’s maintenance costs mean it could sit dormant for years, said Christian Leuprecht, a Kingston politics and economics professor at the Royal Military College of Canada and Queen’s University. “It’s tragic but I just don’t see alternatives,” he said. “There’s a reason the federal government is closing it, because it’s a money pit.”

As reported in March by Paul Schliesmann for the Whig-Standard, former warden Monty Bourke is among many who want to preserve and maximize at least some of that storied past, even if actual development has to include mixed use.

What Kingston doesn’t want to see, he said, is a repeat of what happened with the closing of the British Columbia Penitentiary in New Westminster and the St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in Montreal — and now Prison for Women — which have been abandoned and fallen into disrepair.

He said the newly elected prison museum committee is dedicated to the project and members have a wealth of artifacts and knowledge to contribute.

“I’m committed to preserving the history. I’m committed to building and highlighting that connection with Kingston,” said Bourke.

“I suspect the city would support that. We’re talking benefits such as tourism. We want to be at the table.”

Did I mention it’s waterfront? Kingston Penitentiary beside a busy boat harbor in 2009. Photo: Lucy Martin

Asked by CKWS TV about future possibilities for the federal property, Kingston and the Islands M.P. Ted Hsu replied: “Wait and see what the government does in terms of decommissioning the site so you know what state the site is in, what conditions any future owner has to abide by, for example preserving some of the heritage characteristics and then put together a business plan.”

To be determined, basically.

Kingston residents, what would you like to see there?

And, everyone else, what could happen there that might spark your interest in visiting Kingston, to experience that city’s past and present?

Tags: architecture, canada, crime, history, Kingston Penitentiary, prisons, punishment, tourism, urban development

.jpg)