What does a new atlas of Inuit trails mean for Canada?

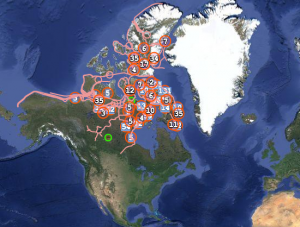

The dog sled and kayak routes of old connected a vast region. (screen shot of Pan Inuit Trails interactive map)

After 15 years of detailed work, researchers have unveiled a unique new Atlas of Canada’s Far North. Pan Inuit Trails, documents and maps traditional place names and travel routes over land and sea. Last week’s release may seem to involve little more than very remote places, but it represents a lot more.

The academic work was done through a partnership involving Carleton University’s Cartographic Research Centre, the Marine Affairs Program of Dalhousie University in Halifax and Cambridge University’s Geography Department.

As reported by Bob Weber for the Canadian Press, the project’s significance is considered (at least) two-fold: “New atlas shows traditional Inuit trail network, bolsters sovereignty case“.

In this part of the world, “trails” included land, open sea or sea ice, as detailed by this coverage of the new atlas, from Past Horizons: Adventures in Archeology:

The intricate network of trails also connected Inuit groups with each other. The atlas shows that, when brought together, these connections span the continent from Greenland to Alaska. Understanding the trails is essential to appreciating Inuit history and occupancy of the Arctic, say the researchers, for which the new atlas is a vital step.

“Essentially the trails and the atlas reduce the topology of the Arctic, revealing it to be a smaller, richer, and more intimate world,” Bravo said. “For all that the 19th century explorers had military equipment and scientific instruments, they lacked the very precise indigenous knowledge about the routes, patterns, and timing of animal movements. That mattered in a place where the margins of survival could be extremely narrow.”

[Note: Dr Michael Bravo from Cambridge University’s Scott Polar Research Institute is co-director of the research.]

The Ottawa connection comes by way of Carleton, where atlas co-author Fraser Taylor is Distinguished Research Professor of Geography and Environmental Science, and in International Affairs.

Speaking to the Canadian Press, Taylor made the point the work was intensely local – bottom up, not top-down.

“We’re not outside researchers coming in to exploit the Inuit. We literally and metaphorically give voice to local people.”

Mapping old trails, it turns out, changes the whole story – as outsiders had imagined it, anyway.

The extent of the web of routes and the depth of those combined stories present a very different view of traditional Inuit culture, Taylor said.

“It should change the idea of the Inuit of an isolated group of people living in small hamlets by the side of the frozen sea into a thriving community which has moved and evolved and interacted over the course of time. It’s confirming what the Inuit have been telling us for generations and we haven’t really listened.”

The trails were used for trading, following game, and just keeping in touch, Taylor said.

“You name it, they’re exchanging it — material goods, stories, myths.”

I find the new atlas cool on several levels: cultural validation, historical preservation, valuable cross-cultural cooperation, smart application of new technology, and so on. And yes, it also advances geopolitical/economic claims that matter to Canada’s modern national interests. (Although it seems to me if evidence native inhabitants actively utilized vast swaths of Arctic regions bolsters Canada’s claims to those parts of the world, the same evidence bolsters native claims to their own territory even more strongly!)

Project leaders say their work only covers part of Canada’s northern regions, there’s more to be done in Labrador, Arctic Quebec, and the far west. Other Arctic regions (Alaska, Siberia, Northern Europe) could undoubtedly benefit from similar efforts, though it remains to be seen if or how all that would be undertaken.

Here’s more discussion about the work’s scope from the project website:

Viewers can also explore the source maps to understand better how this dynamic network of trails, part of the fabric of Inuit territory and history, has been mapped piecemeal by explorers, missionaries, and scientists in the course of cartographic encounters. What is too often lost, however, is a sense of the bigger picture, the territorial coherence of the Inuit people over Arctic waters. These largely encompass and exceed the scope of the hydrographic mapping surveys that have taught generations of students to envision Inuit Arctic waters through the more limited vision of Northwest Passage routes.

According to the CP story, the atlas has garnered rave reviews:

“The importance of doing the work that you have done is monumental is so many ways,” Inupiat whaler and archeologist Qaiyaan Harcharek from Barrow, Alaska, wrote to Taylor.

All in all, it sounds like 15 years of well-spent effort.

Tags: Arctic, canada, Fraser Taylor, geography, history, Inuit, maps, technology

.png)