Then and now: trapping and mineral rights

How well do inherited policies work in changing times?

To be specific, I am mulling over things like trapping and mineral rights. Bear with me and I’ll explain.

When I was a child my father mentioned the term “mineral rights.” I had to ask what that meant. He explained that sometimes land owners do not own all of it, top to bottom. If there was something valuable underneath – like precious metals, coal or oil – the right to those resources might be held by others. We happened to live in a state that retained all mineral rights.

Little Lucy: “Are you telling me the state could stick an oil rig in our yard without our permission?!”

More-worldly father: “It’s possible. But don’t worry, there really aren’t minerals worth extracting where we live.”

What he described sounded completely outrageous. Only with age could I conceptualize how and why such policies could be arguably necessary for a greater social or economic good. (I’m not saying I agree with the concept, only that there are significant justifications.)

By the way, double checking the status of mineral rights in Hawaii I discovered that issue is now leading to disagreements over at least one resource of interest: geothermal energy.

This past week I read a somewhat-related item by Ottawa Citizen columnist Kelly Egan, on an activity few of us encounter anymore: trapping. Egan recounted how a Perth-area property owner was arrested – and eventually fined – after removing traps set on his land, without his permission.

It turns out wild animals in Ontario are “owned” by the crown and trapping is regulated by the provinces. Like mineral rights in Hawaii, there are times when control of that resource can trump what a landowner might want. Under Ministry of Natural Resources regulations, trappers would usually need permission to trap on private land. But in this particular case, according to Egan:

The confusion was over the “high-water” mark. The Ministry of Natural Resources maintains the Crown’s property extends to the river’s highest point in the spring — normally dry riverbed the rest of the year.

A few days ago, a justice of the peace ruled the traps were legal, even though the muskrats and beavers might frolic, feed or cavort on private property in low-water seasons.

The Perth landowner is a nature-lover who likes having beavers on his land. He came away feeling let down by the system. (No doubt the trapper has strongly-felt views too, but those were not included in the account.) For what it’s worth here’s a link to trapping regulations for the state of New York.

By chance I’ve just been reading two books that relate to the fur trade as formative part of Canada. One was Canoeing a Continent: On the Trail of Alexander Mackenzie by Max Finkelstein, an Ottawa-based paddler and author. The other was The Orinda by Joseph Boyden. In it we get the real-life cultural collision of Jesuit missionaries, and some of Ontario’s native people way back in the 1630’s, by way of strong fictional characters: a just-orphaned Iroquois girl and her captor, a Huron war chief who decides to adopt the unusual child. (If you like that sort of thing I recommend this novel. All three perspectives are presented with insight and sympathy.)

Canada’s original inhabitants did not believe in land title, though tribes could and did defended territorial space. Early Europeans in Canada also followed game and fur where ever they found it, or traded for fur trapped by natives.

Fracking in farm country. Photo: shadbushcollective, Creative Commons, some rights reserved

Modernity can bring odd twists to established practices. Are you OK with trappers perhaps having traditional rights to trap on your land – or river, as the case may be? Fur trapping is somewhat out of vogue now. But is that activity so very different than navigational rights, so hotly contested in recent years by recreational paddlers?

Flipping again to mineral rights, back when most European settlers saw an “empty” continent in need of development, there seemed to be less concern about the damage done by resource extraction. As populations and environmental awareness have expanded, more voices question why extraction merits special favor, despite potential negative impacts on communal resources like water.

For sure, this is a complicated and highly contentious issue, as seen in the fracking debate.

But out of genuine curiosity, if you were starting from scratch – empowered to make the rules – how would you set up resource ownership and extraction? How would you balance rights, risks and responsibilities?

Would you be guided by what has held sway in the past? Or focus on what might make the most sense for now and the future?

Tags: books, canada, economy, environment, history, Joseph Boyden, Max Finkelstein, mineral rights, politics, trapping

I believe that mineral rights and high-water rights come from two different historical traditions. Because of the use of rivers, lakes and oceans for transportation, bodies of water are traditionally seen as property of the sovereign government, not the individual, similar to DOT corridors today. This would include land that is under water for at least part of the year. In the case of the trapper, presumably the state issued the permits because the river bank is seen as state land.

On the other hand, it’s hard for me to understand how a corporation could own the rights to dig, drill or excavate under my house and land without my permission. If I lived in fracking country I would fight that encroachment with everything I had.

I think there is a huge difference between mineral rights and the regulated right to take game.

Trapping and hunting are primarily of benefit to the one who traps. All underground resources can benefit millions of people in addition to those who extract the resource.

This is why we have lawyers and the answer is sometimes yes and sometimes no, and subject to change from place to place and time to time.

The cruel fact of the matter is that the government owns all of the land and your private property rights are often very limited. Think of it this way. As long as you pay your taxes (rent), you can continue to enjoy the land with the restrictions imposed by the government. Stop paying your taxes (rent) and the government kicks you out.

End of story.

What did you think the reason behind eminent domain is?

The current idea of property ownership isn’t very old. When did laws allowing posting of property against trespass come into being? Mid to late 1800’s in the US?

When resource extraction of a scale that decimates the environment happens in a place that has few people to observe it many people don’t care. when it happens in a populated area most people feel differently. But it is all the same – except that an open pit mine in your neighborhood would ruin your private property value.

The other issue on property rights is about the rights of nomadic people. Laws preventing trespass and laws regulating national borders have ended the traditional patterns of nomads in places around the world. Fences and extermination have done a pretty good job of it too, along with some of the great migration patterns of beasts.

Someone posted on the In Box a long time ago about a book, Oliver’s War, which tells the story of a civil War veteran ( happy Veterans Day ) who fought the Rockefeller’s attempt to buy the town of Brandon, NY in the ADK Park to establish his private hunting preserve – Bay Pond. Rockefeller and his guests would hunt/poach wild game on his preserve while at the same time preventing locals from getting to traditional fishing holes.

And in Old Forge, the Adirondack League Club established the precedents for posting property against trespass or hunting/fishing in order to prevent native tribes from getting to their traditional hunting areas in the Moose River plains so that Club members would have private access.

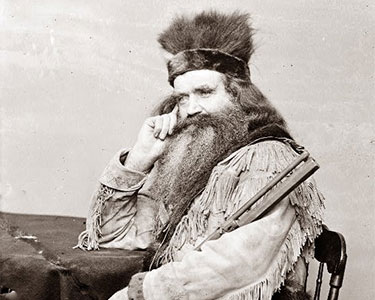

Great photo of the ‘mountain man’. His hair would be a big hit in some cities today.

Seems to me that water is the resource in our region that has poorly defined law. We have settled law about who owns lake bottoms and stream beds. We have litigated the paddler’s navigation question a bit. Most old camps still come with deeded access to water from a nearby stream or lake. There is some law from logging days when water was for transportation and power. Article 14 says 3% of the Forest Preserve can be flooded by dams (about half of that has been). But beyond that I don’t think it’s clear.

For example, what if you own a pond and it’s entire watershed – do you own the water? Or you own a hillside where a brook begins – do you own the water? And is the water moves downstream who then owns it? What about your well water?

In the western states, water law is well defined and has been the subject of long fights. There are limits on what can be drawn from streams and wells by different entities along the way. But water law isn’t nearly as well developed here. On day there will be big confrontations over this.

Or, if I am completely wrong, then maybe someone can explain it here or provide a link….?

Dave, I believe you are correct that water rights will be a big issue in the future and few have been thinking about them. Already some private enterprises have started buying up water rights at what I expect people in a hundred years will be smacking their foreheads over.

I also agree it is a great portrait. I’m guessing the straight up hair is a hat and lore has it that tall hats, feathers, and such were for the purpose of keeping pests like deer flies away. I haven’t made a study of it but supposedly deer flies, in particular will swarm around the highest point on your head, so if your head is taller they stay away from your face.

Credit Dale Hobson for finding the mountain man photo, and many of the images that accompany various posts.

He has a gift for knowing what “look” will make a post greater than the sum of its parts.

knuck it was me

I posted about oliver’s war.

worth the read

ps- that’s an interesting barrel rested in mountain man’s arm

Henry rifle?

it’s an over under for sure. brett would know!!