Desperately seeking…rain

Well, it’s no secret that it’s been hot. And very, very dry. Lawns are brown, gardens are parched. Farmers are steeling themselves for dismal yields, maybe even crop failure.

Bad as that is, the worst of it may be the scope of this drought. As represented by map graphics in this New York Times article, a majority (55%) of the U.S. is experiencing conditions ranging from moderate to extreme drought. The accompanying article is also gloomy about any short-term relief:

The latest outlook released by the National Weather Service on Thursday forecasts increasingly dry conditions over much of the nation’s breadbasket, a development that could lead to higher food prices and shipping costs as well as reduced revenues in areas that count on summer tourism. About the only relief in sight was tropical activity in the Gulf of Mexico and the Southeast that could bring rain to parts of the South.

According to the article, fully one third of counties across the U.S. have been declared drought disaster areas, permitting them to apply for federal aid programs.

When my family moved to the Ottawa area in 1999, one thing that amazed us was the lack of irrigation. We kept looking for agricultural ditches, sprinklers – something. Seeing none, we wondered how do people water around here? (What? They don’t? It rains in the summer?! Who knew?)

My husband was born in Arizona and grew up in California’s central valley. He can recall how his grandparents in Phoenix could open a sluice gate and flood their lawn on a scheduled basis. Stockton, where he went to high school, is surrounded by agriculture that requires irrigation.

On Maui, where I grew up, whole watersheds on the lush, windward side of the island were harnessed long ago into intricate irrigation systems that deliver water to sugar fields and (later) resort communities in sunny, dry areas. My high school was named after Henry Perrine Baldwin. The son of missionaries, he became an early sugar planter and supervised the construction of East Maui Irrigation System circa 1876 while still recovering from losing an arm in a mill accident.

These days, environmentalists and cultural advocates on several Hawaiian islands are trying to restore natural stream flows – which is a struggle as the dry sides have come to depend on the water that’s imported – or stolen, depending on one’s point of view.

Anywhere you go, water is always valuable – and often contentious.

How strange – how marvelous – it felt to live where abundant water was part of the natural cycle. Indeed, some of the last dozen summers in Ottawa have felt too wet!

Not this one, though. Statistically, the past 12 month stretch from July-June in Ottawa ranks as the hottest and driest on record.

Not this one, though. Statistically, the past 12 month stretch from July-June in Ottawa ranks as the hottest and driest on record.

The Rideau and South Nation watershed areas are officially in a stage two drought (explained here), which could easily hit stage three if conditions stay parched.

Residents in the Rideau watershed are currently asked to suspend non-essential water use and reduce overall consumption levels by 20%. Lawns across the region are crackle brown. As you’d expect, growers who supply farmer’s markets are feeling stressed. Despite a burn ban, there have been a number of brush fires in, or around, the Ottawa region. The number of forest fires in Ontario is way up for 2012. As of Friday, there’s a new fire of some concern near Algonquin Park. (Also detailed here.)

Meanwhile, urban Ottawa draws its water from the Ottawa River, which is big enough that the city doesn’t seem overly concerned about running out. Residents supplied by that system are not under restrictions. It seems counter-intuitive, but Ottawa officials recently requested that homeowners do water their lawns, to alleviate fire risk.

But many medium-size communities surrounding Ottawa use well water for their municipal systems and some are concerned about reduced replenishment rates. CBC reports that the town of Almonte recently imposed a ban on outdoor watering which seems to be helping matters, somewhat.

Most rural residents in smaller communities hereabouts (like me) are on private wells and have to worry about the possibility of running dry.

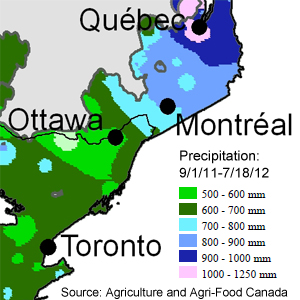

That’s my region. How’s Canada as a whole doing? I can’t find current data in the same sort of percentages as cited above for the U.S.. But significant areas of Canada are experiencing drought conditions.

Here’s a link to a technical discussion of drought and trends from Environment Canada. The long-term outlook is not certain, but looks rather challenging:

All Global Climate Models are projecting future increases of summer continental interior drying and associated risk of droughts. The increased drought risk is ascribed to a combination of increased temperature and potential evaporation not being balanced by precipitation (Watson et al., 2001). However, considerable uncertainty exists with respect to future precipitation, particularly on a regional and intra-seasonal basis. Furthermore, relatively little is known regarding changes to large-scale circulation and, since these patterns have a significant impact on temperature and precipitation over Canada, the occurrence of future drought remains a huge knowledge gap.

There may be a few “winners” in all this disaster. As reported by the Toronto Star, a number of Canadian fertilizer companies expect to benefit overall:

This growing season is already a write-off, but for the next one, farmers will plant more seed and use more fertilizer and insecticide as they chase those higher corn prices.

That means bigger profits – and soaring stock prices – for companies such as Agrium Inc., Potash Corp., and Mosaic Co.

One need only think back to the Great Depression to know that hard times do happen. As if the collapse of the stock market wasn’t bad enough, terrible dust bowl conditions scoured the land, giving rise to the dour nickname of “dirty thirties”. The weather and the economy did get back to more normal conditions, eventually. But it was a grim stretch to endure.

A few years ago, the weather was sufficiently odd in Canada that the environment started to register near the top of people’s concerns. Then things settled down and economic issues climbed back to the top of the polls.

I predict a similar rise in environmental worry across the U.S. electorate. If you believe in global warming – and see these conditions as a wake-up call – then maybe that’s a silver lining. The trouble is, as soon as normal weather patterns resume, heightened concern tends to subside too.

How do you view this drought and how’s it affecting you?

Tags: agriculture, canada, drought, environment, weather

Here in Indian Lake we have had over 2 inches of rain during the past 7 days.

Where would California be if it didn’t import water from out-of-state and disrupting the ecology of rivers? Like California, for the garden we draw water from the creek that passes through our property . The rocky substrate (limestone) is so close to the surface that there is little capacity to the aquifer. But across the past 14 summers this dry spell is not unusual for us. I believe the creek has been bone dry 4 times in that span and following that in about 2 two weeks refreshing rain arrives. Living on well water and with that 50 gallons a day gave us an appreciation for what we had. So I’ve have seen what we have now before. Given that there was a cistern in our 110 year old house, the previous owners were familiar with water limitations too.

Thanks for the excellent map graphics!

What is fascinating was how bad 1950-1956 was for a long lasting drought in major portions of the US. Worse in many respects than the 1930’s.

Also from a statistical point, when does a drought become just the new normal rainfall? I mean if you look at Texas, particularly west Texas, they have had a drought essentially for the past 40 years. At some point it is not a drought but what is normal I would think?

“The trouble is, as soon as normal weather patterns resume, heightened concern tends to subside too.”

Just like the conditions after the dust bowl in the ’30s. I don’t remember it taking a big government program for the weather to recover.

Actually, the Department of Agriculture stepped in and taught farmers everything they know about soil and water conservation. In places like the North Country, hundreds of thousands of acres of trees were planted on soils deemed too weak to sustain continuous cultivation. In addition, the dust bowl era gave birth to big government. Who do you think put all those Oakies to work, building the great dam projects, mountain road projects, and nearly every red brick high school in the country.

The weather took care of itself, but the government took care of the people.

Here in Potsdam, we had nearly three inches of rain during our terrible wind storm. The streets were flooded, and the force of that much water moved things around even in lawns that one might have presumed to be pretty flat. That water was a welcome break in our drought, but three days later, it’s all gone. Too much of it ran off into the river.

My water barrels are all full though.

JDM,

I hear you about government programs having not very much to do with weather.

But I think there were major efforts to change agricultural practices and reduce soil erosion, which had become so devastating in the ’30’s.

How broad were those efforts? How many were under government auspices? Or was it a case of asking extension agents to educate and hoping farmers would adapt on their own?

I don’t know as much about this important topic as I might. Seems to me preventing erosion, arresting desertification and rejuvenating exhausted soil is terribly important stuff.

Checking reference material on line, here are a few examples of government responses that appear to have made a difference:

1935 “April 27: Congress declares soil erosion “a national menace” in an act establishing the Soil Conservation Service in the Department of Agriculture (formerly the Soil Erosion Service in the U.S. Department of Interior). Under the direction of Hugh H. Bennett, the SCS developed extensive conservation programs that retained topsoil and prevented irreparable damage to the land. Farming techniques such as strip cropping, terracing, crop rotation, contour plowing, and cover crops were advocated. Farmers were paid to practice soil-conserving farming techniques.”

And from 1936:

“May: The SCS publishes a soil conservation district law, which, if passed by the states, allows farmers to set up their own districts to enforce soil conservation practices for five-year periods. One of the few grassroots organizations set up by the New Deal still in operation, the soil conservation district program recognized that new farming methods needed to be accepted and enforced by the farmers on the land rather than bureaucrats in Washington. ”

The first one sounds rather top-down. (But still probably a good thing.)

The second one seems to be a nice degree of bottom-up/owning the problem.

In my view, when it comes to government programs, some stink.

Some work well. And I guess the rest are somewhere in the middle.

I’m fine with getting rid of the stinkers.

I’d hate to throw out the keepers though!

Lucy and tootightmike:

These soil education programs you refer to are great. I’m guessing the actually information that was taught came from private sector farmers-turned-innovators.

What they did not, nor could not do, was change the climate. If they could have, why didn’t they? That would be a more efficient use of government dollars. i.e. make it rain.