Halloween Memo: Why witches still matter in modern America

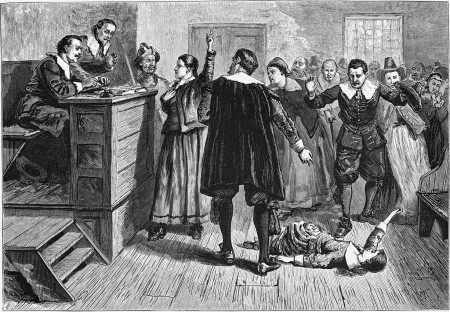

Witchcraft at Salem Village. Engraving from “Pioneers in the settlement of America: from Florida in 1510 to California in 1849,” author William Crafts, 1876. Artist: unknown, public domain

Every so often, usually in this season before Halloween, witches and witchcraft push their way into Americans’ consciousness. A few weeks ago on Garrison Keillor’s Writers’ Almanac, he noted in 1692 eight people in the Massachusetts Colony were put to death for the crime of witchcraft, marking the end of the so-called Salem Witch Trials. According to Keillor, the deadly persecutions in Salem “started when two young girls began displaying bizarre behaviors” and eventually accused their neighbors of practicing and supporting witchcraft.

The New Yorker also recently treated the Salem trials, in an article highlighting the notion — as so many have done before — that the program against accused devil-worshippers was a kind of localized mania, peculiar to a fragile Puritan culture on the American frontier. “New England delivered greater purity but also introduced fresh perils,” wrote Stacy Schiff. “Stretching from Martha’s Vineyard to Nova Scotia and incorporating parts of present-day Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Maine, it perched on the edge of a wilderness.”

The trouble with this account is that the witch trials in North America didn’t start with two young girls, nor were they a phenomenon peculiar to rural areas or primitive frontiers. For hundreds of years, but particularly during the 16th and 17th centuries, the best and brightest minds of Europe believed in magic and considered Satan to be an active agent in the world, capable of corrupting those with weak minds or spirits.

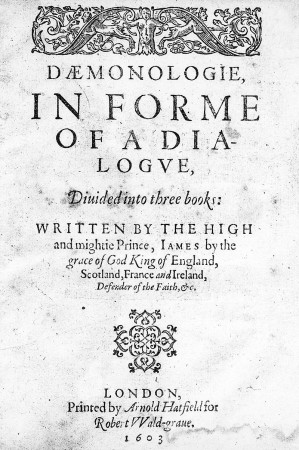

Title page of the 1603 edition of Daemonologie by King James VI. Photo: Wellcome Images

It stood to reason that the Devil would have human allies and it made perfect sense to the politicians, intellectuals, and bureaucrats of their day that those allies should be found and killed. When King James VI visited Denmark in the 1580s, witch trials were common and were widely accepted as a necessary practice. On his return to Scotland, James’ own ship was beset by storms, which the monarch believed to be an attack against him conjured up by witches. He hustled off to attend a new series of witch trials in Edinburgh where eventually as many as 3,000 men and women were put to death. He later wrote his own witch-hunting tome called Daemonologie.

The British king wasn’t laughed at or condemned for embracing the ludicrous notion that secret cults of men and women were using supernatural forces to harm their neighbors, influence geopolitics, and bring evil into the world. The vast majority of scholars, philosophers, and clergy agreed with him. Across Europe through the late 1500s and early 1600s, as many as 80,000 accused witches were put to death in the decades prior to Salem. Many of these officially sanctioned murders took place in highly developed, cosmopolitan parts of the Dutch, German, and Bavarian states.

England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire all had specific laws and legal frameworks for treating (harshly, as you might imagine) those accused of practicing black magic. One “witch hunter,” a fellow named Nicolas Remy “was responsible for the deaths of more than 800 individuals, most of them women, in Lorraine,” according to the excellent study of the period called Witch Craze by Lyndal Roper.

Roper found that the vast majority of those who carried out these legally sanctioned murders weren’t possessed by some kind of hysteria. They were highly educated men, who, for the most part, acted deliberately upon the best available ideas about how the world worked. In most cases, men and women were put to death only after what government officials deemed to be proper and thorough trials and a careful weighing of the evidence.

It’s also important to remember that during this period even great thinkers like Copernicus, Kepler, and Isaac Newton–men who helped invent what we now think of as modern science–were convinced that dire supernatural forces were at play in the world. When not developing the calculus and sniffing out new ideas about gravity and the orbital patterns of our solar system, Newton was often locked away consulting wizard’s tomes and experimenting with magical formulas.

Moreover, Christian Europe regularly tore itself apart on a much larger scale over fears involving supernatural influences. The Thirty Years War, which ended just half a century before the Salem trials, was in many respects far more devastating than the Second World War. It was fought over minor differences, baffling to us now, that involved various Christian superstitions and rituals. When it ended, some German provinces had lost half their population to the carnage.

Newton himself never feared persecution because of his scientific or his magical views. Rather, he lived in a constant state of secrecy and anxiety because he rejected the generally-accepted idea that God was somehow divided into three materially different parts, known as the Holy Trinity. Was the “Holy Ghost” a true facet of God? If you didn’t think so, you would very likely be imprisoned or put to death. In parts of Europe, in fact, it was far safer to be a practicing astrologer or wizard than a Roman Catholic or a Jew.

Taken out of context, the killing of a few dozen women in Salem seems like a horrific aberration, a brutal hate crime, the kind of thing that happens on a primitive frontier. But in the context of a world where people regularly murdered their neighbors because they happened to read a Bible printed in the “wrong” language or because they said their prayers with slightly different phrasings, the witch persecutions in North America begin to look both more normal and more horrifying.

Portrait of John Dee, court sorcerer of Queen Elizabeth I, who retired in honor to a clergyman’s post. Artist unknown, Ashmolean Library collection

One peculiar wrinkle to this story is although vast numbers of people were persecuted for the supposed crime of witchcraft, it was fairly common during the same period for respectable members of the community to practice some forms of magic under certain conditions. Popes regularly employed astrologers. Kings and emperors kept alchemists and even court wizards on staff. John Dee, who was court sorcerer to Queen Elizabeth I, was occasionally threatened with punishment and sanction. But he also enjoyed high honors throughout her reign and was eventually given a clergyman’s post in his retirement.

It’s hard to sort out why some practitioners of magic–men as well as women–were put to death in unfathomably brutal ways, while others were consulted by powerful leaders, allowed to publish books, and given prestigious posts at universities and in churches. I’ve never found a convincing explanation for this weird inconsistency. It is also unclear why we continue to associate witch-hunting with American primitivism, when in fact it was a mainstream part of high European culture for centuries. The last English “witch” was put to death in 1682, a scant decade before Salem.

If there is a takeaway from the witch persecutions in Europe and North America, it isn’t that it was a form of frontier mania, practiced by zany puritans frightened of the dark woods. The takeaway, rather, is that whenever we believe in magical forces to such a degree that we are willing to judge, persecute, and even kill our neighbors based on those beliefs, terrible things happen.

By the early 1700s, the Enlightenment emerged with new, secular ideas about justice, scientific fact, and the importance of a civil judiciary shaped by reason and due process, not faith and zeal. It is this lesson that still resonates in America today, as some politicians, public officials, and citizens still insist that some of our neighbors should be judged and condemned based not on their character or their actions, but on supernatural ideas recorded in ancient books.

As long as we insist upon viewing the world in terms of good and evil, we will continue to drive ourselves crazy.

At those times that the world seems to be devolving into irrationality and violence, it’s comforting to look back in history and remember that we have always been irrational and violent……oh dear, wait a minute.

Interesting reading. However, I came away with the impression that the witch craze had largely subsided by 1692. The notoriety of the Salem witch trials suggests they were in fact an aberration in their time. If so, then some kind of further explanation for the trials seems in order.

It is accurate that witch trials had begun to subside in frequency and ferocity by 1693, but it is a widely held misconception that they were aberrational or outside the norm by that time. In fact, there were other witch trials in North America and in Europe in the 1690s. On both continents, witch trials continued into the early 1700s and they weren’t officially banned in England until the 1730s. The last women to be burned alive as witches in Germany died in 1738, nearly half a century after Salem.

The point I’m making is that the Salem trials were part of a clearly established legal, religious and psychological framework established in the 1500s — not part of some kind of ‘mass hysteria’. Yes, that framework was beginning to be questioned, but the women murdered in Salem died at a time when witches were still considered a real and plausible threat to the public good. It was educated men and women, people of wealth, and establishment figures taking part in these legal processes, not mobs with pitchforks.

Finally, the triggering events in Salem (rivalries, superstitious accusations, misunderstandings, etc.) combined with the lack of proper legal protections for those accused of such crimes closely resemble the earlier and larger witch pogroms in Europe.

–Brian

What? The witch trials are over? What about this witch in Texas?

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/ahmed-mohamed-texas-teen-cuffed-over-clock-withdraws-from-school/

Interesting and well done. Sadly, witch-hunting, in the form of liberals and conservatives demonizing each other, continues in America today. The religious aspects of the conflict show that for all our supposed enlightenment nothing much has changed.

The Islamic terrorists kill people for the same reason people killed people they accused of being witches.

When you can demonize people for any reason, this allows you to feel good about killing someone. By killing, you prove to yourself that you are the good guy fighting evil.

This is exactly what we do when we execute people.

Witchcraft-related killings are still a reality of life in much of the developing world, and occasionally violence of this kind even marks more fringe Christian communities in the US. The Word of Life case in the Southern Tier this fall allegedly involved some concern in the congregation that members of the church had dabbled in witchcraft. When I googled this issue, I found a remarkable essay written by an evangelical Christian suggesting that Roman Catholic worship is to blame for increases in “demonic activity.” It’s a remarkably persistent concern among a small slice of believers in various faiths and sects. – Brian, NCPR

I agree with Phil above. That is what I got when I read the New Yorker story. It sounds even as if they were in a sense embarrassed from what happened. Very little was recorded by the “official” historians of the time.

According to the article several dogs were also accused of being witches and executed as part of the Salem thing. Wonder what they did?

Remember when Steve Martin was the Medieval Barber on SNL. They threw Jane Curtin’s daughter into a vat of water. If she floated she was guilty if she sank she was innocent (and dead of course since they forgot to pull her out!). When Jane came and found her dead they congratulated her on the fact her daughter was not a witch.

“always been irrational and violent”. Luckily we live in one of the most peaceful times in human history. You juts can’t tell since we all get to see the violence right after it happens even if miles or oceans away.

“But in the context of a world where people regularly murdered their neighbors because they happened to read a Bible printed in the “wrong” language or because they said their prayers with slightly different phrasings, the witch persecutions in North America begin to look both more normal and more horrifying.”

This, I think, is the crux of the persecutions for the most part. The fever of witch burnings in Christian lands accompanied the introduction of printed books and bibles printed in common language. Witch hunts were a means of control coinciding with the various Inquisitions. In France Protestents were made to convert to Catholicism and soldiers were even posted in homes to be sure the conversion took. Protestant churches were burned and many Protestants secretly practiced in forests so as not to be seen. People practicing religion in a forest? Either witches or Protestants, doomed.

Rallying the masses to fear others who are not like you and using that fear to pit one vs the other is very old in human history ( get ready, here comes the Godwins Law bit … This ones for you Dale ) as we have seen in Hitler and the Nazis’ persecution of Jews, gays, Roma and others.

We still do it today, only the details change, but we can limit the spread of fear and ignorance. Or at least try.

My last thought on witches is this.

Before there were any of the major religions of today, there were various beliefs we now call pagan. All of the religions of today have their roots in paganism.

A truth none of the major religions want to admit to is all religions, including witchcraft, all forms of paganism and atheism are belief systems. Believing is what humans do when they don’t know. Believing is filling in the blanks.

No matter how strongly anyone insists there is or isn’t a god, there is no way to prove or disprove the existence of a god.

In fact, at a scientific level, there is no way to prove or disprove this is the only universe there ever was or ever will be. Simply put, we are locked in a moment of time and space, and have no way to see beyond the moment of this particular universe. So we comfort ourselves with this or that belief.